This chapter contains scenes of violence, death, fleeting graphic violence, mild body horror, psychological and existential distress, and suicidal ideation.

Across Ayvarta rushed the grey tide. From the bordering nations of Mamlakha and Cissea, once a part of the same land, the grey tide charged Shaila and Adjar. It turned along the curve of the Kucha, capturing Tambwe and Dbagbo on its sides, headed east, northeast, to the red sands, to Solstice, and beyond, across Ayvarta.

The Grey Tide snuffed out the fires lighting the beacon of socialism.

Aster, Hazel, Postill, Lilac, Yarrow, gone. It was done. The Grey men won.

Ayvarta turned grey, and the grey men marched in their uniforms. From then on it was all pickaxe and plow for the red people. Coldly they were watched as they toiled until they died. Iron for the factories, grain for the tables, gold for the coffers, oil for the burners, thousands of miles away in the land of frozen hearts. Disunited the world watched them.

But wealth was not eternal. Over a hundred years the plow would hit rock and the pick would find no more rock to hit. Coffers dried of yellow gold and the black gold no longer drew from the coffers. Again the grey men would march. At first it would be with honeyed words. Requests, exchanges, fair trades, free markets, supplies and demands; backed by a diplomacy of unquenchable thirst on one side and helpless desperation on the other.

There was no longer one red people. Everything looked red to the grey.

Every nation had something they wanted. Lubon, Hanwa, Kitan, Svechtha, Helvetia, Higwe, Mankarah, Bakor, Borelia, Occiden, and Cassia – the eyes would turn to them.

At first with honeyed words. “You have things we desire. Give them to us.”

But what was desired could never be given fairly or peacefully.

Grey uniforms, marching, marching, told the world needs more picks and plows.

On would the grey tide go; bombs fell before them that exploded like earthbound suns, mobile fortresses like battleships on land crushed whole cities, planes that covered the globe in the blink of an eye subjugated all resistance, tanks impregnable to weaponry rolled over the new plowers, the new pickers. From one land to the next until they were all grey.

Such was the way. Wealth clamored for wealth. Power needed power.

And then what? Once the wealth was drawn and the power had gone?

She could see no more of it. She did not want to. It could not happen.

13th of the Postill’s Dew, 2008 D.C.E

Solstice Dominance – City of Solstice, Sarahastra District Hospital

Several days since the Ayvartan Revolutionary Declaration

Outside the room door the nurse pleaded for her patient to be left alone.

She informed the unannounced visitors that the patient that they sought was not doing well, that the fighting in the streets had her skittish, and that she was vulnerable and needed rest because of her deteriorating, chronic condition. The Hospital was unaffiliated, she said, and they wouldn’t allow access to patients to either side of the conflict.

In her eyes they were all the same, she went on to say, thugs, murderers–

Kimani grabbed the nurse and brandished a pistol, pressing the barrel to her temple.

“I’m not asking for your political opinion; I am demanding you move aside now.”

Weeping and choking with sobs, the nurse nodded slowly and unlocked the door.

Kimani nodded toward the hallway, where someone else had been watching the scuffle. Her companion approached, a tall and slim child in worker’s overalls, a boy’s long button-down shirt and a red beret too large for her head. Kimani was about 1.9 meters tall, a head taller than the nurse; for an 8 year-old Madiha was tall at 1.5 meters.

She was almost the nurse’s size.

Madiha passed the two of them, turned the door knob, and peeked inside.

Silently she looked over her shoulder and nodded her head affirmatively to Kimani.

“Go in.” Kimani said. She released the nurse, who hurtled down the hall in fear.

They had reached their objective, but their time was running out. They hurried inside.

From the bed, a shriek. “Messiah defend me; a demon assails me in this dark hour!”

Madiha averted her eyes from the bed, rubbing her upper arm in discomfort. She was silent. Kimani rubbed her left temple in frustration. She walked past the bed and looked out the windows. Madiha could hear the rifles up the block; pow pow pow. Just by craning her head a little she could see the streaks of smoke across the sky. All around the city there was smoke and death and gunfire. She had caused some of it – a crucial sum, in fact.

On the bed the woman thrashed away from the visitors, covering herself with her sheets. She had lost all of her hair, and her eyes looked sunken. Her complexion was paler than ever, and her Ayvartan was more difficult to understand through her accent and through the slurring of her voice, probably a result of painkilling drugs.

She seemed to be wasting away.

“I’m not a demon, Sister Benedicta. I’m Madiha, Madiha Nakar. I want to ask you–”

Sister Benedicta lashed out. “You are! You are a demon! From the moment I saw you I knew! I knew you had been wrought by the devil herself! From your skin to your eyes!”

Kimani returned from the windows, hands over her eyes with exasperation.

“We don’t have time for this, but she won’t talk if I thrash her anyway.” Kimani said.

“Yes, please do not thrash her. Or anybody else if you can help it.” Madiha said.

She had become very eloquent for a child over the past year.

Reading tough newspapers and books, to understand socialism, had done a lot for her speech. But she was still a child – she still looked at sister Benedicta with helplessness. This was a person who had always wielded immense power over Madiha, and still did.

She still held something precious, too precious to strike her down for her sins, but so precious she would always withhold it for its power. The situation was intractable.

“Does she even know?” Kimani said. “Maybe she has no idea, Madiha.”

“I know she knows.” Madiha said. She sighed. She had gladly gone to chase after this ghost, but now she understood. “She’s not going to say it, because she knows it hurts me.”

From the bed sister Benedicta smiled, an evil, cruel smile.

“For all anyone knows or cares it was the devil that made you child! It’s the devil that controls you! You brought the devil to a place of worship and you brought it to this city, and you cast God out of this city, and you ended God’s enlightenment and blessing here, and that is why your people kill each other on the streets! The Good Lord who gave His flesh so we would be free of sin, and you spat in His face! You Ayvartans are all the same!”

Kimani grit her teeth and nearly raised her pistol to the nun, but Madiha held on to her arm, so that she would not shoot her. She grabbed her arm and pulled her away from the bed and toward the corner, and though Kimani was much stronger than her, she allowed herself to taken. Madiha was certain that she would have shot otherwise. She had already shot a lot of people today – and yesterday, and the day before. It was becoming easy and routine. It was more frequent than Madiha ever thought. All of the adults around her were whipped into a mute fury, and in Madiha this manifested only as a skittish fickleness.

Certainly she had wanted to come here.

She had convinced Kimani to take her from the safety of the compound, into the fighting streets, and out to this hospital, when they learned that a sister from Madiha’s old orphanage was here, one that might know. But seeing her in this state, and seeing the city in this state, and Kimani in this state; Madiha’s problems and questions looked so small. She just wanted to get back to her comrades in the compound now.

“Madiha, I don’t want to let this demagogue hurt you any longer.” Kimani said.

“She’s a sad old woman who is all alone and it doesn’t matter.” Madiha said.

“It matters! You have a right to know. I thought you wanted to.” Kimani said.

“I thought I wanted to know too.” Madiha said, avoiding Kimani’s eyes.

“Couldn’t you peer into her mind? Couldn’t you pry her head for your answers?”

Holding her hand tight the child shook her head despondently. “I could potentially search her mind for it, but to do so I would have to endure all the hatred she feels too.”

Kimani rubbed her free hand down her face again. Madiha slowly let go of the other.

“Shacha and Qote are going to be quite annoyed with me for this. I put you in danger.”

“I’ll talk to them. Sorry I roped you into this. It was silly. I’m being really stupid.”

Sister Benedicta watched the two of them with trepidation while they spoke. Finally she let out a hollow, croaking laugh. “God’s Fire is coming child! You and your barbaric horde will be brought low by flame! You turned from his light, and now taste the inferno!”

Madiha looked at the laughing, screaming nun in terror, and she saw past her, through the window; a pillar of smoke and fire rose up toward the heavens in the distance.

“Chinedu! Is that–”

“A Prajna!” Kimani shouted in disbelief. “They fired one Prajna! How, at what–”

This was all the time that God or whoever gave them on the surface of Aer.

In the next instant the earth shook, the building rumbled. The 800mm shell of the Imperial Prajna supergun had soared through the sky with a trail of fire, and crashed through the roof of the Sarahastra hospital. Had the structure been any smaller, certainly everyone inside would have been annihilated instantly in the massive blast.

But the district hospital was a mammoth of concrete, and the gargantuan explosive only split the building in half. Prajna’s shell impact was like an earthquake and the burst shattered every window, cracked every floor and threw everyone off their feet.

When the shell hit Madiha felt the shaking, and her vision blurred, and she lost all control of her body. Walls cracked, the roof collapsed, Sister Benedicta was crushed screaming in her bed, the floor crumbled, and then Madiha fell, soaring through the ruined gap, through the smoke, as the hospital’s twin halves settled away from one another like a poor carve cut out of a large cake. She felt nothing, and saw nothing.

She was suspended in a void.

She would not see anything again for years, not as herself. But in that instant she had fleeting vision – she saw through the eyes and the mind of Chinedu Kimani.

Kimani had fallen against the door during the quake and the burst.

Much of the room had gone – a wedge shape across half of it had sunk into the slope of debris that became the cleavage between the building’s halves. She was in terrible pain, as though her body had been put in a bag and viciously crushed. Not one bit of her seemed to have gone unscathed, but she was not bleeding, and nothing felt broken.

Blearily she moved her legs, her arms. She was not dead.

She grabbed the door knob and pulled herself up to a stand.

The Hospital had sunk toward its side, and the once flat floors were laid at an angle. Sister Benedicta’s bed was gone with the wall and much of the floor, all open to the air. Kimani saw the street, pockmarked with mortar craters and a handful of bodies; the sky, streaked with smoke. Across the gap where the building split, she saw its other half, the rooms laid open, survivors crawling and scampering away, and the dead lying and dangling.

She inched her way to the room’s new edge.

Atop a steep hill of debris below she saw Madiha, thrown over the remains of the nun’s bed. There was blood on her, over her peaceful face, over her little chest, on her still hands.

“Madiha.” Kimani said, but she did not voice the words.

Her lips moved but there was nothing above the sound of fire and the wind and the sifting of dirt and the shifting of debris. Her heart quickened, and her breath left her. Her mind was battered by hundreds of images of this girl, barely eight or nine years old (she did not know exactly, nobody knew exactly). Madiha screwing her eyes up while reading difficult papers; Madiha taking time out of her deliveries to ask if hot and cold formed a dialectic; Madiha, eyes white hot with rage, the world stirring around her presence.

She had gone through so much, too much, much more than any child should have – and every step of the way she affirmed that this was what she wanted. Everyone ahead of herself – everyone the equal in a perfect world, but she always put them higher than herself.

She was no demon.

A crash; the door to the room finally collapsed. Kimani turned over her shoulder.

At the door, a man in a brown uniform and a cap approached.

Both his shaking hands held a submachine gun – an automatic weapon the Imperials had purchased in small quantities from Lubon, like a small rifle that loaded many rounds from a vertical magazine atop the bolt group. Judging by that weapon he was one of the Imperial Guard, but he was young, probably a cadet in an ill fitted uniform.

He stood at the doorway, standing slanted toward the right.

“Don’t move, communist!” He shouted. “Come closer with your hands up!”

“Don’t move, or come closer?” Kimani said, her eyes wide, her lips quivering.

He grit his teeth and approached, his weapon up to his face, rattling in his iron grip.

“Don’t move!” He shouted. “I’m going to disarm you! You are under arrest!”

He took tentative steps forward, eyes scanning the room through the iron sights, obscuring by the magazine. Kimani raised her hands; and before he could reaction she hurtled toward him, shoving his gun against his face and away from her. She seized his belt with her free hand and drove his own knife through the bottom of his head.

She stared down at his body, breathing quickened, livid. Her hands shook with rage.

Kimani took the guard’s weapon and his ammunition and charged out of the room.

She had to get to the lower floors.

In the adjacent hallway a pair of men in imperial uniforms stopped upon seeing her thrust out of the room, and coldly she raised her carbine, slid to a knee, and opened fire, holding down the trigger while the bolt on her gun flailed, and the bullets sprayed from the barrel. Both men hardly recognized her appearance before automatic fire punched through their chests and bellies, and they clutched their wounds and dropped to the floor, flopping like dying fish. Kimani picked the explosive grenades from their belts and ran past.

These were not mere policemen – imperial grenades were blocks of explosive in a can and would have set ablaze any suspects and any kind of evidence. This was a purge.

Two floors worth of stairs had been crushed together like layers on a flattened cake, and a hole leading to a steep slope of piled up staircase rubble was the only way down. Downstairs she heard a commotion and though she could not see anything in the dark hole below, she knew more men were coming. She pulled the pins and threw the grenades down the slide, taking cover behind what was left of a balustrade.

She counted and closed her eyes.

Twin explosions, gouts of flame rose up the hole; a series of screams confirmed her suspicions. Kimani leaped down the hole, and her feet hit the rubble and slipped out from under her, and she rolled roughly down onto a bed of men concussed and burned by the grenades. Her whole body ached, but she picked up her gun from the floor, attached a new magazine atop the bolt group from the belt of a dying officer, and pushed on.

They didn’t matter; she didn’t matter.

Kimani didn’t know how many floors down she was, but she found out soon enough. Running from the slope’s landing, she shoved through a broken door, into a room full of dazed patients. Like Benedicta’s room, their wall was open to the air.

She hurried to the edge.

She saw Madiha again, still unmoving, at peace, her little mountain meters below.

She saw a dozen men further below her, combing through the rubble, climbing the mound, standing at the foot of the slope where it had overtaken the street and road. All were men in imperial uniforms. Several more rushed through the street and into the building, armed, yelling orders, shoving around any unlucky survivors they encountered.

There was probably a whole platoon of officers involved.

Silently, Kimani took a knee near a piece of wall, large enough to shield most of her from any fire coming from below. From her pack she withdrew a flare gun and aimed for the sky above the street below. She fired and as the bright green flare burst into a flash under the cloudy sky, she peered from cover and shot the carbine at the men below.

Firing in controlled bursts, Kimani raked the men climbing around the rubble with bullets, moving from target to target, pressing and depressing the trigger quickly.

At first they stared in rapt confusion at the light from the flare, but when the bullets opened on them each man went his own way, either hitting the dirt, leaping from the slope, rushing to the remnants of the walls opposite her perch, all scrambling for cover or escape.

None of them were fast enough.

Four bullets on a man, pause, scan, four bullets on another; just moments apart, grazed and perforated and pricked, none able to escape. Six men went down in a vicious succession, knees and shoulders and arms bleeding, hit wherever Kimani could first hit them. Her element of the surprise now spent, she ducked behind rubble, her barrel hot and smoking.

Bullets struck the concrete at her back, and men started screaming for backup.

Kimani dumped her magazine and set it aside with few bullets left.

She attached a new one.

Six men down, six left on the street.

Below her, the slope of rubble spread out over the street and onto the road, and here the men had been stationed in the middle of the street at the foot of the rubble-strewn mound. All of these men were now likely shooting and screaming at her.

Kimani saw bullets go flying past, and compacted herself as much as possible.

Chips of concrete fell over her and saw dust kicked up. Every officer on the street had zeroed on her perch and were emptying their guns on it in fully automatic mode. She could scarcely count the rounds, and the lull between shooters was not enough to retaliate.

She grit her teeth and tried to count the bullets. She had to focus on this to survive.

Each of them had the same gun she stole – a Mitra 07. Thirty round magazines, she repeated to herself, and tried to feel all of the impacts, ignoring the jabs against her head and shoulders and limbs as the sprays of bullets sent fragments of rubble flying every way. Mitras were inaccurate and pistol caliber rounds lacked the punch to penetrate concrete.

But she was focusing on another problem with the gun’s design.

She counted and counted.

Sharp cracks started to issue from below.

The hail of gunfire abruptly slowed and stopped.

Kimani stood fully upright over her chunk of the broken wall and boldly resumed her attack on the men, pressing the trigger down and planting her feet, her upper half exposed. As though wielding a hot sword she slashed through the six men on the street with a furious wave of gunfire, perforating each man in turn by simply turning her waist and arms while her gun emptied out. Barrels smoking, magazines near empty and bolts jammed hard, the men fell aback with their useless guns clutched in dying grips.

Mitras clogged up easily.

After fifty or sixty rounds you could expect the bolt to get stuck.

She cycled the bolt manually, ejecting a round through it.

Wouldn’t do have it catch too.

Replacing her magazine, Kimani rushed along the ruined edges where the rest of the wall once stood, threw her gun down onto the hill, and she dropped, and skillfully dangled from the jagged cliff with both hands. She released herself as her momentum carried her against her half of the building, and landed on the remains of another floor below.

She was at least 5 meters closer.

She could see Madiha quite well now.

She was injured, unmoving, probably concussed; maybe even dead. Tears welled up in Kimani’s eyes. What would it have taken for Madiha to have a better end than this?

Had she killed more people, planted more bombs, would it have made a difference? All she wanted to know was who her parents were – that was why she left the compound, why she went to face a woman who had tormented her through her whole life.

Madiha had seen and done many things but she had only been a girl.

Ancestors damn it all.

There was no time for this.

Kimani took a breath, and immediately she took off running. She leaped off the edge toward Madiha, arched her body, bent her knees; she hit the ground with her feet first and with gargantuan effort pushed herself to roll, diffusing the fall. But her roll smashed her into a heap of rubble and she came to lie on her back, breathing heavily.

Her back felt split open, and she couldn’t stand. Kimani reached out her hand. Madiha was only centimeters out of her grasp. She struggled and struggled, feeling her shoulder burn. Her hand came to lie atop Madiha’s little fingers and she curled them. I

‘m sorry, she thought.

“I’m sorry. I couldn’t be what you needed. We couldn’t be.” Kimani whimpered.

She heard boots, and soon saw shadows stretching over her. She felt something press on her side, and then kick her over on her side. They forced her hand from Madiha.

“Take her to the garrison, she’ll know where their base is–”

As one the shadows turned, and there were shouts.

There was a scramble, movement, gunfire.

When the shadows returned they were gentler.

“Lieutenant Kimani, ma’am, we came as fast as we could!”

It was her comrades, come fresh from the fighting upstreet.

“Spirits defend, Madiha’s very hurt! We need to take her back now!”

Kimani was too injured and exhausted to reply or to explain, and would not be able to supervise the actions of her subordinates. She gasped for breath and her consciousness wavered as the Red Guards approached offering aid. Her vision went dark and in turn so did the last window that little Madiha, with her powers, had left into the world.

Madiha fell and fell and fell with no destination. She was gone from reality.

This connection severed, Madiha would go on to lie in a coma bed for two years and awaken in a new world. Ayvarta was won, socialism was slowly implemented. She would live, but despite the triumph of her allies it would be a long road for her. In the care of the state, a pubescent Madiha, her muscles wasted, speech gone, her precocious intellect eroded away, would go through several years of a new, painful childhood, out of which she would only return to her old healthy state at the tail end of her teenage years.

She caught up in her education, found love, and moved on.

All of these things, and what happened before them, she would go on to forget.

The Madiha known as Death’s Right Hand and The Hero of the Border would know only through hearsay and from the tellings of comrades that she performed heroically in the Civil War, that she spent years unmoving, and then years unable to speak coherently, years rebuilding her bodily health. She did not know these things first-hand.

To her these would be only legends and distant history, as if performed by a distant sibling. Thus there remained a strange, alien emptiness in her that she would struggle to fill. What was a person, what truly was a person, other than a vessel for experiences?

What was a human while empty of history?

28th of the Aster’s Gloom, 2030 D.C.E

Adjar Dominance – City of Bada Aso, Southeast, Riverside

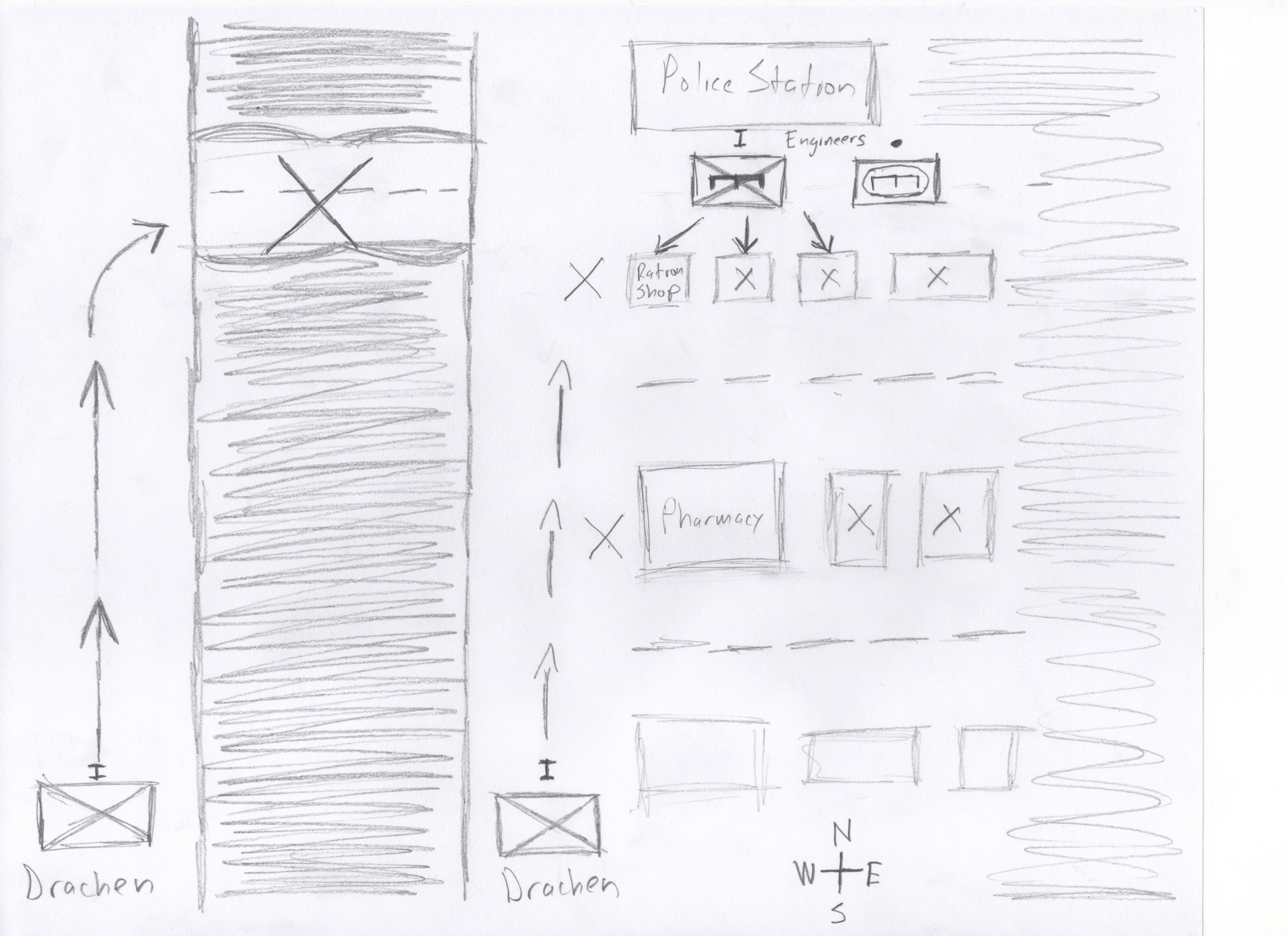

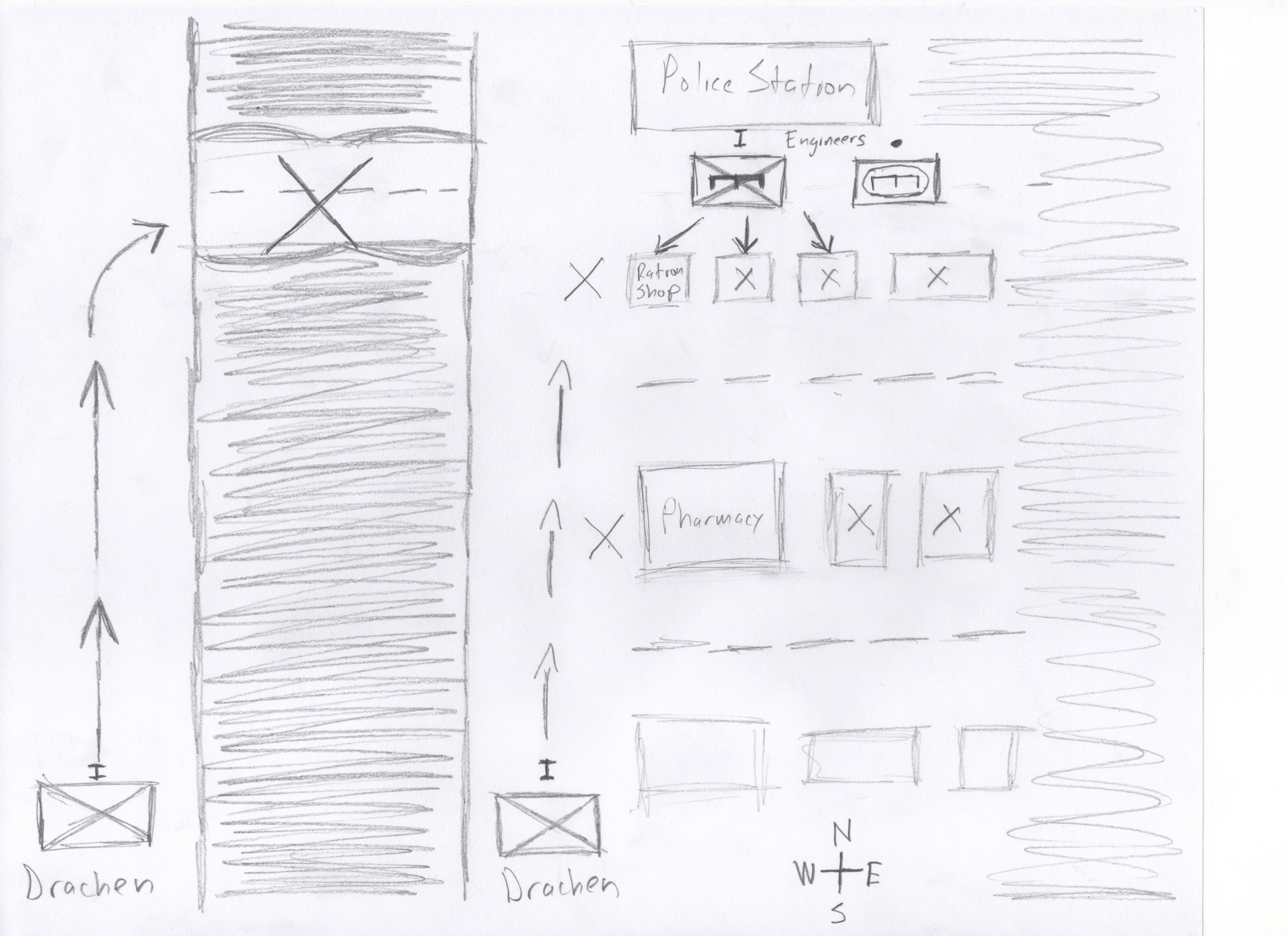

Batallon De Asalto “Drachen” advanced, overrunning the first and second lines in Umaiha. In the midst of the rain, under the rain of shells and rolling explosions, and against the ruthless advance of the Cisseans the Ayvartan lines broke down. While the Ayvartans hid behind defenses the Cisseans moved swiftly, squadrons advancing under effective covering fire, bounding across what cover could be gotten, swiftly and fearlessly charging through killing fields with smoke shells and suppressing artillery protecting them. Losses were inevitable, but the battalion exceeded Von Drachen’s expectations.

They killed and scattered hundreds.

Von Drachen even had to call in Von Sturm’s security and leave captives for them!

Cissean troops soon ran unopposed through the Umaiha riverside.

A handful kilometers more and they would be in the next district, in time for the next phase of the battle. On each leg of the march, a preparatory bombardment from 3 guns pounded each block three times, just in case. But no more Ayvartan defenses seemed to move to challenge them. It was conceivable that they might even be home free!

His men were spoiling for a fight, growing confident. After the second defensive line folded, the Drachen Battalion advanced as a continuous charge more than an orderly march. It became difficult to call in preparatory bombardments when the line moved so fast.

“Don’t get too far ahead!” Von Drachen shouted into his radio.

Riding in the back of Colonel Gutierrez’s car, soaked in the rain, he raised a pair of binoculars and squinted his eyes, but no concerted effort could really show him what was transpiring across the river from him. He saw his troops charging ahead and started losing track of them. The Umaiha’s eastern side in the city was more thickly populated with big buildings that served as offices and factories, barracks and company shops, in its previous life as a corporate district for imperial heavy industry, and then socialist industry.

There was a lot more infrastructure to stare at and weave through than in the western bank of the river. Even so the units there kept too much a lead on the units on Von Drachen’s side of the river, as though eager to win a race to the city center with their allies.

“They’re getting spirited!” Colonel Gutierrez said. He sat in the passenger’s side while his restless driver ferried them along the surging river. Von Drachen did not mind the waves, though the previous occupant of the car’s pintle mount had been killed by one.

“Spirit is good, but order would be better.” Von Drachen said ruefully.

“Ah, Raul, let them have their victory!” Colonel Gutierrez replied.

“Very well, but don’t call me that.” Von Drachen replied.

Von Drachen looked through his binoculars again.

His bombardments raised thick plumes of smoke and dust in the blocks ahead of the march, blowing across the sky from the storm winds. They were difficult to see, and so were the men headed for them. Thick rain and the cover of light posts and balustrades and decorative plants turned the formations of his men into an indistinct charging mass that had a clear beginning nearest his slowly advancing car but no visible end.

He craned his neck to stare at the slowly passing second and third stories. Many bore fresh scars from shells and mortars. Smashed windows, broken doors; chunks of roof and wall, or whole floors, collapsed under the punishment of a stray 15 cm shell.

“Estamos cerca de el proximo puente, General,” said the driver. They were close to the bridge, one of the last in the southeast. A few kilometers further the Umaiha would curve away out of the city interior and they would have a shot at the center.

“Keep moving at pace, stop only for contacts.” Von Drachen said. He put away his binoculars and procured his radio. “How are we doing on howitzer ammunition?”

He was cut off; the Umaiha stirred, and a wave crashed along the side of the car.

Von Drachen held on to the gun mount, and his radio and binoculars were both thrown from his grip. It was like a wave of cement had struck him, and not water, it felt solid as a stone punch. Pulling off of the side of the river and toward the opposite street, the car stopped near a desolate little flower shop. Von Drachen leaped off the back, nonchalantly wiped himself down under the awning, and hailed a passing radio man.

He took his backpack radio and sent him off.

Kneeling beside the pack, Von Drachen adjusted the frequency and power, and picked up the handset. On the other end his bewildered artillery crew asked if he was alright.

“I am fine, thank you for your concern. I was struck by unruly water.” He replied.

On the other end the crews expressed their hopes for his continued health and safety.

“Indeed, I am grateful. Now, I wanted to ask: howitzer ammunition, how are we–”

A violent explosion in the east cut him off; and cut several dozen men worse.

Von Drachen’s vanguard on the eastern end of the river, two dozen men riding atop and alongside one of the Escudero tanks, marched along the street passing by an innocuous two-story state pharmacy straddling the riverside, shuttered and presenting no immediate threat until its first floor violently exploded in a surge of glass, metal and concrete.

Fire and smoke burst through every orifice in the structure, consuming the men and the tank in heat and debris. Chunks of rubble flew across the street and over the river. For the men crossing the building death was certain; anyone within five meters was flung and burnt and battered, while out to ten and twenty meters the concrete and glass shrapnel, where not stopped by another structure, cut and grazed and injured unprotected men.

Dozens of men were killed, dozens more injured, and hundreds were given pause.

Its foundations annihilated, the top floor slid off in pieces and buried whatever was left of the tank. Only the cupola on the smashed tank turret peeked above the mound of debris. At once the columns on both sides of the river lost all of their previous spirit.

Von Drachen sighed audibly and slammed down the radio handset.

“That was a demolition charge.” He said. “Gutierrez, car!”

At once Von Drachen lifted the backpack radio into the staff car and they drove ahead, the column making way for them. They stopped across the river from the blast site. There were dead even on their end of the river – Von Drachen saw a corpse lying nearby, a towel dropped over his head, thick with blood. Bloody chunks of rubble were strewn around him.

Von Drachen seized a pair of binoculars and a hand radio from a nearby sergeant.

Only the width of the river separated the bulk of his troops. He could see them now.

They were close to the next bridge, leading to the old police station on their maps. Shells had smashed much of area. Holes had been blown through the station’s facade and roof. Two blocks down from the station, the Cissean line stopped at a row of buildings ending in the smashed pharmacy, the remains of which blocked the riverside street.

On the radio Von Drachen ordered his men to climb over the tank in groups of six, engineers in the lead, in a bounding advance. Hauling a minesweeping rod, six engineers climbed the mound, and held at the top, waiting for six more men. They descended under the cover of the new arrivals; another group of six climbed, took position, and waited for the previous six to descend. Hastily his men formed up and started tackling the mound.

“Treat the locality as hostile.” Von Drachen warned them. “Someone had to be nearby to detonate those charges. Someone is watching you. They know that we are coming and they are out there. Watch the rooftops, windows, doorways and the higher stories.”

Across the river the men raised their hands to signal their acknowledgment. They moved cautiously, with the minesweeper at the fore, and a rifle pointed in every direction. One man kept his eyes forward; the minesweeper on the ground; two men covered the path upstreet once they crossed into the intersecting road; two more men watched the windows and roofs for movement. Ten meters behind them the next group of six moved in.

Von Drachen turned to the men at his side.

“From this bank, we shall organize a crossing of the bridge toward the police station. Have a dozen men move in first – if they cross and it is not a trap we move the tank next, and then more men a dozen at a time. Have everyone else stand at the balustrades and watch the other side of the river, providing covering fire if it becomes necessary.”

There was chatter on the radio. “General, nos encontramos con una mina!”

“Take care of it, carefully.” Von Drachen called. They had found a mine. Nochtish troops were equipped with bangalores to clear minefields, but they had neglected to issue such things to their Cissean allies. “Ayvartans use old style pressure mines. You can pick it up and defuse it as long as you don’t trigger the plate atop. Wedge it out carefully.”

Peering across the river, Von Drachen watched as his men approached the mine and marked the area around it. One of his engineers used pair of thin metal tools to slowly and gently lift the mine from its position, probably made to appear as though a tile or a stone. They raised the object and eyed it suspiciously. They looked stupefied – Von Drachen saw them touching something attached to the mine and felt a growing sense of alarm.

“Que hacen?” Von Drachen asked, raising his voice desperately. What are you doing?

One man raised his radio to his mouth. “General, la mina tiene un hilo–”

Von Drachen’s engineers vanished behind a sudden flash – the mine detonated into a massive fireball and a cloud of smoke. Under the rain the fire turned quickly to gas.

A crater was left behind, and the men had been blown to pieces.

Boots and shards of equipment and flesh lay scattered around the hole. It was pure explosive; no fragments whatsoever, no finesse, just a block of explosives.

That was no mine, they had picked up another demolition charge.

Urgently he called the rest of his men. “Hurry ahead, we can’t be certain when more charges will be detonated! There is no way to be safe but to close in right away!”

His men forgot the careful bounding that characterized their previous approach, and each group of six took off running the moment they hit the ground on the other side of the mound. Some of them rushed up the connecting street to check the nearby buildings for demolitions personnel; most charged down the side of the river with abandon.

Nothing exploded, nothing engaged.

They crossed the street and huddled at next building across, just south of the bridge.

Farther ahead, on the bridge, the first group of twelve Cissean men crossed without a hitch. They made it to the ration place across the street and joined their compatriots.

They signaled the tank, and it started crossing, testing first the bridge’s reaction to its weight before committing. Tracks ponderously turning, it inched across the flat brick bridge. Water surged, causing the tank to pause momentarily with each temporary swell.

Von Drachen took this opportunity and called his howitzer crews once more. “Remain in place. I will hail soon for support. What is our ammo situation like at the moment?”

“Se nos estan acabando las cargas,“ his artillery officer responded.

We’re running out of shells.

Von Drachen rubbed his own forehead. “Well that’s a pity, but how many are left?”

On the bridge the tank was nearly across when the men shouted for it to stop. Several meters away a manhole cover budged open, and the men were quick to point their rifles.

At once the tank stopped. It pointed its cannon at the manhole and waited for orders.

A pair of leather bags then flew out from the manhole and landed at the soldier’s feet.

Von Drachen saw the events unfolding and switched channels immediately.

“Step away from them! Throw grenades down that hole!”

His men scrambled back toward the bridge, and cast their grenades into the manhole once safely away from the bags. Several bright flashes and loud bangs followed and smoke trailed up from the underground. Several minutes of stand-off followed the blasts, but the bags did not go off and nothing more was seen or heard of from the open manhole.

“Those bags are certainly a trap.” Von Drachen said. “Affix bayonets, hold your rifle as far out as you can manage, pick them up by the shoulder straps, and cast them into the river. Do not jostle them too much. Timed satchel charges would have gone off already so that can’t be it – the bags may be rigged with grenades that will prime if you open the flap.”

Swallowing hard, a pair of infantrymen did as instructed, picking up the bags gingerly by the very tips of their bayonets, holding their rifles by the stock. They could hear things moving inside the bag. They called back; Von Drachen felt he was right in his suspicions.

“Pitch the things away, and once they’re blown, I want men in that hole.”

Despite the raindrops across the lenses of his binoculars he saw the same odd glinting that his men did when they lifted the bags high enough. A wire, dripping with the rain. In an instant both bags detonated, again in a bright, hot flash of fire. Demolition charges.

But the two explosions across the river were not isolated.

Blasts rolled across the streets, buildings going off like a domino effect.

Fire and smoke erupted from buildings all along the column on the eastern side of the river, as far back as the adjacent streets where the first tank had been lost. Rubble flew everywhere as seemingly the entire street across the river from Von Drachen was burnt and flung and smashed to pieces. Behind his men the ration store exploded; beside them the buildings nearest the ration shop went up into the air as well, and fell with the rain; and before them, the center of the bridge collapsed under the tank in a prodigious fireball. What remained of the vehicle slid backwards into the river and washed away downstream.

When the fires settled, there stood less than half the initial strength of the Cissean force, many swaying on their feet, ambling without direction along the ruined riverside street, some even falling off through the shattered balustrades and into the river. Of the survivors, half of them, perhaps a quarter of the four hundred men he had deployed, seemed to have their wits about them, and began to cross the streets and reconnoiter the aftermath.

Von Drachen, covering his face with his hands, grumbled. “I hope that tank doesn’t clog anything up. Messiah defend, do these people not have access to mines or grenades?”

“Street blown, bridge blown, bags blown, buildings blown. Both their tanks are out. We have unfortunately gone through most of our heavy explosives in the process.”

Every flash of lightning seemed to scramble the audio, but they heard the voice on the other end clear enough. Sgt. Agni gave the order. “Engage the enemy from your positions.”

Submachine guns, pistols and shotguns in hand, engineers gradually emerged, from the sewer tunnels, from the police station, and from within the rubble left behind the destroyed buildings. Huddling underground, they had set off charges, and maneuvered themselves into good positions where they could engage from behind newly strewn debris.

Gunfire commenced with a slug from a breaching shotgun.

Shot from inside the remains of the ration shop, the slug traveled through a slit in the rubble and punched through the jaw of an unaware man forty meters from the ruins.

Retaliation came immediately – a Cissean saw the attack and threw a grenade through the slanted, ruined remains of the ration shop window. It soared over the engineer’s cover, and it clinked down onto the floor behind him. In a split second reaction the engineer hit the dirt, and the grenade went off, scattering fragments across the interior of the ruin.

No more was heard from him. But there were still dozens ready to fight in his place.

Across the river rifles started to crack against the empty ration shop. Everyone took the sudden death of the rifleman as evidence of a sniper, and became distracted. While the Cisseans unloaded on the ration shop, engineers appeared further upstreet from sewers and ruin tunnels, and hurried to fighting positions closer to the enemy.

They hid inside building ruins and behind the piles of debris, waiting.

Within moments of the ration shop being cleared, they attacked.

Bullets suddenly rained on the Cisseans in the eastern side of the river, pummeling the balustrades from within a hundred meters. Engineers fired long, careless bursts, taking little time to aim. It was all fire for effect, and their aim was to draw the enemy away from the police station. Ayvartan forces concentrated on both sides of the line of buildings that sat across the street from the station. Around the demolished ration shop and its adjacent structures, submachine gunners sprayed the Cisseans by the river and near the bridge ruins.

Lashing trails of bullets easily picked off men still disoriented and dazed from the blasts. Men with any sense left in them rushed away from the open street, and the remnants of the column thus split into two – everyone farther north huddled near the bridge and in the shadow of the police station, while the remaining Cisseans were pinned near the corpse of their first lost tank. On the eastern bank of the river the air was thick with lead.

Previous demolitions insured that Cissean cars would find no opportunity to flank the Ayvartans, and to deploy their other heavy weapons the invaders would need to expose themselves. Trickles of men bounded through the ruins of the Pharmacy, looking to flank, but found themselves trapped by the length of the Ayvartan column, and easily rebuffed.

Heavy fire soon started to pick up from the more populated western side of the river. Machine guns and mortars fired desperately across the river to little avail. Ayvartan engineers kept themselves well-concealed in the rubble. They fired from around mounds of debris or between gaps in still-standing walls, and easily avoided retaliation by ducking or backing away. Light mortar shells failed to shatter their cover or to suppress them.

Automatic gunfire could not penetrate the rubble or accurately target the gaps, and in rain the Cissean rifle troops were visibly poor marksmen. All the men close enough to throw explosives had been forced into hiding. Both sides settled into a stalemate, exchanging fire and expending ammunition but hitting nothing. The Drachen Battalion’s options to terminate the impromptu strongholds in the eastern bank were growing limited.

Limited, but not entirely nonexistent, proven when the 15 cm shells began to fall.

It had been the hope of the Ayvartan engineers that pushing close to the enemy column would increase their reluctance to unleash their heavy artillery, but it had been a fleeting hope. Heavy shells started to crash around the eastern riverside in short intervals, pummeling the street, flattening the ruins and casting into the air the mounds of debris. The engineers hunkered down and waited out the bombardment. It was not the explosions that killed, but the shifting rubble. Several men and women were concussed and buried and crushed as the shells blasted rocks around and closed the gaps in the rubble piles.

But they accomplished their goal – none of the shells threatened the police station.

While the engineers dug in as best as they could in the rubble, across the bridge the Cisseans moved pair of mortars closer to the bridge and loaded an odd pair of shells into it. Suppressed by artillery the engineers barely spotted the mortars and could not figure out their unique significance until the shells crashed on the other side of the river without an explosion. Instead the shells stretched a series of steel cables across the eastern bank.

Minutes later, under waning gunfire from the suppressed engineers and safely away from their own bombardments, more Cisseans started crossing the fallen bridge.

Sergeant Agni walked in circles around the unmoving body of Major Madiha Nakar, rubbing her own lips and chin, thinking through the events. A simple engineering survey had become a sudden crisis. As she and the Major drove around the Umaiha earlier in the day, unbeknownst to them a lightning-fast and incredibly well-coordinated Cissean attack smashed past their defenses one after the other, making a distressing amount of progress.

Artillery and heavy weapons were systematically deployed to suppress and overrun every Ayvartan position. It was unlike any attack the Ayvartans had faced so far, and unlike every attack they believed the Cissean forces capable of launching.

This felt like what Nocht’s previous attacks should have been.

Carnage reigned across the front line, and in the scramble communications between forces was negligible. Laggard troops awoke far too late to effectively defend themselves, and were smashed past, and either killed, sent running, or forced to surrender in a panic.

Before anyone knew what was happening, the Engineers were stuck guarding the old police station along the Umaiha Riverside. Unluckily for them, the Cissean’s 15 cm sporadic rolling barrage had, of all the things it could have hit, smashed the ceiling right over Madiha. Though Agni had managed to free much of Madiha’s upper body from the rock, her lower body was not pinned by debris, but by a solid piece of concrete roof.

She was not crushed – smaller rubble wedged under the slab kept much of the pressure and weight off Madiha, but her legs were still pinned solid under it and she could not be pulled out. Sergeant Agni ran through the options in her head, her pulse quickening.

Worsening matters, none of the radios available to her seemed able to reach Army HQ.

She had told Madiha that she would bring her back safely and she would fulfill that objective. It was not merely a matter of loyalty or strategic convenience. It was something she wanted to do. As personal as it could be for her, this was a personal errand.

She had to succeed.

Sergeant Agni was a KVW Engineer.

She had the crisis training.

Fear was not a powerful thing to her.

She felt it – everyone always felt it. It didn’t go away.

But it didn’t stop her, it didn’t hurt her like it did before. Other people allowed fear to paralyze them; Agni was never overwhelmed by fear anymore. Conditioning, special drugs, sensory deprivation, hypnotic suggestion, noise exposure: a battery of tests and therapies removed from her those feelings. She had been told, during a lecture, that shaking was a response by the body – the mind wanted the body to go fetal, to curl up and feel safe, and the shaking signified your struggle against those urges, a struggle that kept you upright.

Agni never shook; her body categorically refused to go fetal. She lacked those urges.

But her heart beat faster.

Her fingers rubbed quickly against her chin and lips, satisfying an impulse to fidget. Excess energy; it was going somewhere. She was told this was natural. Was it as natural as wanting to go fetal? More? She supposed the conditioning wasn’t perfect.

Rejecting impulse, gaining clarity, emptying the mind of terrors; those were some of her reasons to join the KVW, to take the crisis training, to lose feeling. Everyone had reasons. Nobody was brainwashed. People thought it was magic. Maybe it was.

At first it felt like it. It felt like magic to be able to focus. To be able to think clearly.

Now, however, it felt like a curse. She kept walking, kept thinking. But to no avail.

Try as she might Agni could not escape the logic that her mind was settling on. She had no compulsion to reject the most straightforward, achievable solution available. Had there been no urgency she might have tried a substandard but appeasing solution. Under pressure, however, she could think of only one course, recurring horribly in her mind.

She would have to risk blowing off Madiha’s legs to save her.

“I’m going to need a satchel charge.” She called out. “Without getting a tank or a tractor in here, the only way to remove this thing is to smash it into smaller chunks.”

Outside what was left of the lobby, an engineer standing guard brought a bag and handed it to the Sergeant. His eyes wandered across the room where the Major was trapped.

“How is the situation outside?” Sergeant Agni asked.

“Cisseans have effected a crossing. Their artillery has subsided and they have begun to push forward in numbers. Our column between the blocks is making it painful.”

“How many casualties have we incurred so far?”

“Less than them.”

“Keep the teletanks in reserve. We will need them to have a chance to escape.”

“Yes ma’am.” He eyed the satchel. “Are you sure you want to use that?”

“Yes.” Sergeant Agni answered simply.

“It may hurt the Major.”

“I know that better than anyone.” Agni said. Thanks to the lack of feeling in her voice, this statement sounded almost polite, though she meant it to sound definitive and forceful.

She opened the satchel.

Inside was a block of explosive material. Carefully she cut a smaller piece off the larger explosive block, and picked the detonating mechanisms out of the satchel, affixing them to the small piece. She laid this smaller explosive atop the slab trapping the major.

“I’m not a believer, so if you are, you should pray.” Sgt. Agni said to the guard.

She did not really know the Major and did not think she could be a friend.

How did one cross that threshold between mere person and friend?

Agni did not know, but she felt Madiha was a valued comrade, and knew that she wanted to ease that pain and vulnerability that Madiha had clumsily shared with her before and that she had clumsily responded to. All of the logic of her mind pointed to the fact that she could not possibly have left her behind to die. It would have been inhuman to do so.

It was more than just her value as a commander, but her value as a person.

Feeling had been lessened, but not totally lost to her. Faith, she hadn’t ever had before.

Filled both with feeling and a longing for faith, Agni primed the charge and took cover.

? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ? ?

This was a place outside the contention of human senses.

To the sight it was simply a void, but it felt populated by much more than could be seen or felt. Speech took on a different form here, where something said could carry content far outside the literal. Thought was difficult; she felt as though every word she said in her mind to conceptualize a feeling was contested by a dozen others, as though a shouting match. It was difficult to convey simple concepts, and nothing seemed straightforward.

Certainly this felt like her innermost reaches should feel – she felt cold but safe, in a familiar space that was forbidding and smothering all at once. An internal forum.

All at once, however, she coalesced – and something left her.

There appeared in this void two forms. One was her own body, or the thing she could most closely conceive of as a body. It had little definition to it. She did not possess the tall, lean, strong form that she remembered having. There were insinuations of it, such as the outline of her dark, orderly neck-length hair style, her thin nose and lips; her strong shoulders, the outline of her breasts, her trunk, hips; but much of it was as though vaguely sketched, hollow, as though a gel that could be seen through. She was ephemeral, vulnerable. A strong wind could scatter her form and reduce her to a cloud of gas.

Across from from her stood a smaller but infinitely stronger and more solid presence.

It was Madiha as an eight year old child, at the time of the Prajna attack in 2008.

“We should not be here. It should have been over. Please cease this struggle.”

Child Madiha was speaking. Her voice was so strong she felt she would be blown apart.

But the other Madiha could not speak. Her mouth could not move. She could not reply and tell her that it was not her who was struggling, not her who had to be spoken to. She was more than ready to vanish. Her entire existence hung on by the tiniest thread.

“You are nothing but a fabrication to extend a farce. I’m what is real; the true self that was hidden. I’m your power, your strength, your blood, your flesh – in short, your purpose. We had a purpose, once, and we do not anymore. It is time to be gone.”

She wanted to scream at the Child and tell her to finish it already but she couldn’t.

“We were supposed to die, back then, because our influence on the world had been felt. Violence can be transformative, but the perpetrator is a tainted, broken instrument.”

She taunted her, spoke right in her ear, and there was no defense against it. She was helpless toward this child with burning eyes and a cutting tongue.

Not a word could be said back to her.

“Let us make good on history. Let us be gone and free. That is our purpose. It’s in the blood. Blood in our veins and hands. Tainting us. There’s no escaping it without ending it.”

Madiha felt completely helpless. She could not respond, she could not escape.

Silently she cried out for someone, for anyone, to please quiet this all.

Something else left her – she felt a piece, a tiny piece, cut from her.

Across from both her and the speaking Child Madiha something formed.

It was another Madiha. She was in uniform. Child Madiha was tall for her age; at 8 years old she was already 150 centimeters. When the uniformed Madiha stood up to the child she was over 30 centimeters taller, and seemed almost to tower over her. There was a look in her face filled with defiance and anger. She scared the ephemeral Madiha, the formless, helpless onlooker. Who was this? This was not who she wanted around.

She felt trapped between two horrible beings now. None of them could just give her the escape that she desired. None of them could finish this mess. They were in a stalemate.

“I am not broken.” Uniformed Madiha said.

She had a powerful voice. It resonated across the space.

Child Madiha was not impressed with her. She kept speaking, almost as if still into the ears of the ephemeral Madiha. “Our time has passed. We have no future now.”

“You’re the only one without a future. We continued to make something of ourselves.”

“You stole, to construct a facsimile. You were never anything. Without a past you don’t have a present or a future. You have only what you took. It is time to pay for that.”

“We were not born into the world to collect images and sounds. None of that matters in the end.” Uniformed Madiha snapped back. “We are people, born for more than that!”

The Child Madiha spread her lips in a smile, baring sharp, shining teeth.

“We were born to kill, conquer, and die. We counter the stagnation that occurs at the end of an era and prevent the world from freezing to a halt. We did our part. We fought our war, the war we were destined for, just like the stories. We won and we were meant to be gone. Our existence after that is a burden. The Revolutionary must die so the innocents can have a world at peace, for a time. Can you imagine a world after a war, where all the soldiers still live, still thrash and struggle with the fight in their hearts? That is why you must lie now, never to awaken. You must die so that there can be peace for others at last.”

“I reject that. I’ve already told you that we are more than all of that.” The Uniformed Madiha replied. From the sidelines the Ephemeral Madiha started to choke up. She felt like she was melting. This intensity was a lot to bear. “We are more than soldiers and killers.”

“We are not people. People build, monsters destroy. Which one have we been?”

“What do you think we’ve been doing? What have you been seeing all this time?”

“What have you ever built that can make up for all that you’ve destroyed? You are not needed to build; nobody asks your kind what kind of a world you wish to have. There is nothing to you but the fight, the clawing and the bleeding. You were born out of violence and you thirst for it. That is why you can’t stay out of the fire and dust. Why you must die!”

“Now you are just talking past me. Who even are you?” Uniformed Madiha shouted. “You are not us at all! Why are you in here? Who allowed you to speak on our behalf?”

Child Madiha ignored the outburst. “It is in our blood to kill and to destroy. We are marred by it. Why do you think we have this power? We used it before. We killed and ruined. We said it was for a cause, but did we ever have a choice? We acted like animals.”

Between the circling combatants, the other Madiha curled up and closed her ears. But she could not drown them out. Everything they said was wired directly through to her brain.

“This is not in my blood. I was not born to this. It will not pass from me to another. It is not a name, and it is not a bloodline. It is not about heredity. I deny all of that – it is a role, a responsibility. This is from my people and for my people; it exists to protect our community. That is why what we have been doing can only be called building.”

Uniformed Madiha started to look clearer to the Observer Madiha, and she herself started to become less ephemeral; but that Child Madiha was turning dusty, like a poor TV picture. The Child Madiha spoke ever more viciously, her fangs sharper.

“You do not control this; history is against you. History has set your path, and you will follow. You cannot defy the terms. You were born for this, you did it, and you must do it.”

“We will make it different then. We will defy that mandate of history.” Madiha said.

“It does not work that way! Words have meaning! It is in your biology! You are different! You are a monster! You have no power here to make the rules! This is a place of blood and flesh. You will kill, conquer and die, because it is your inheritance!”

“That consensus is an imposition upon us and I do defy it. I defy you.” Madiha replied. “You are not us, not a part, and certainly not the whole. You are some antiquated thing. This is a new era, and we can shape it. We can shape the terms. You are an intrusion.”

“I am the greater part of you! What do you have other than me? You are alone!”

Now, it was the Uniformed Madiha’s turn to smile and reveal her fangs.

“We have her. We have the real you – we found her again.”

Uniformed Madiha made a pulling motion toward the formless Madiha.

Though the onlooker struggled to get away, thinking that the touch would be the most agonizing experience, she felt the gloved hand seize her by the arm. There was no pain. Her grip was not malicious. It was the gentlest touch she had ever felt – it was not a seizing of her arm. That had only been her fear, her projection. The Uniformed Madiha stroked her shoulders, and knelt down to look her in the eye, and embraced her, firmly and affirmingly.

She was not ephemeral and she was not formless, not anymore. She was Madiha at age 7, a tall, precocious, strange child with no place to be and seemingly nothing to live for, but who took steps to the world of the adults, and who fought, in every way that she could, in ways that defied all reason, that defied the bleak future that had been ordained for her. She wept with the realization that she had never died and she had never gone. She had always been the one in control. She had always been herself. She was not lost.

She was not something other. She was a human, a person.

Always, she had been Madiha Nakar, and that had always meant something.

She was not born for an endpoint. She was born to be; and she was. She always was. And she was not merely things she took from others. Because they “took” too. They all shared, through joy and through sorrow. All of it had made her unique onto her own.

None of it was blood; none of it was clay. It was a chorus, pulsing through the ruins.

Madiha Nakar. Even if the memory was lost, and even if the future blurred.

Across from her the other child lost her face.

She became an outline carved into the void and could not judge them anymore.

Her voice was completely lost, because Madiha had regained all of her own.

“It has never mattered what we were back then.” Uniformed Madiha said. She was in tears; Child Madiha was in tears as well. “We were not born solely to die or solely to kill. Nobody is; we had the agency to do what we did and to choose what we want. It is not in our blood. Back then what we wanted was to lash out against the brutality and injustice that we saw. That was important to us. But we are more than that moment in time. We are more than the scope of time. We are everything we build, and that is everything we do.”

The Madiha who had been taken and co-opted, regained her voice.

“Thank you. I understand. And right now, we want to survive.” She replied.

Uniformed Madiha smiled and looked upon her with tearful gratitude.

“Yes. Thank you.” She said. She stood, and took the child’s hand. “Let us go.”

Hand in hand with herself, Madiha left the void of her anxieties more complete than she entered it. She knew now everything that had happened. Now she could move forward with the world. Melding, the hands of her selves became one. She was just Madiha Nakar.

There was a warm flash, a shiver of premonition and the sound of the rain.

She was back in the flesh, where the world could be changed.

South District – 1st Vorkämpfer HQ

Von Sturm had been reduced to pacing the headquarters, kicking at the puddles of water forming along the ground. Without word from the 2nd and 3rd Panzer Divisions, and with bad news from Penance road, he became lost in thought. Fruehauf was at first glad to leave him to his devices, but soon radio traffic was coming in that he had to listen to.

She plugged a handset into Erika’s radio, flipped a switch to override her headphones, and took responsibility for the call. She raised her hand to wave Von Sturm over.

“Sir, your security division is requesting transport for prisoners.”

“What?” At once Von Sturm stopped his pacing and turned to face Fruehauf and the row of radios and operators. “What prisoners? They’re supposed to be guarding the rear!”

“They apparently captured many Ayvartans near the Umaiha.”

“When did this happen and on whose authority?”

Fruehauf picked up the radio handset and spoke into it. She then put her hand over the receiver and turned over her shoulder to stare at the general while responding.

“Under your authority sir, according to them. I know you have not spoken to them at all but that seems to be what they believe. They claim it was your orders that they go out to the Umaiha riverside to help secure Von Drachen’s prisoners.”

Von Sturm paused, eyelids drawn wide. He had a look of dawning revelation.

“Von Drachen! That bastard took my sword so he could trick my security division!”

“Excuse me, sir?”

“Nevermind!” He crossed his arms in a huff. “Fine, if he took prisoners he’s making progress. Tell them I’ll send a few Sd.Kfz. B from the reserve. How many prisoners?”

Fruehauf raised the handset to her ears again. She spoke, listened, nodded.

“Seventy-two.” She replied.

“Good God.” Von Sturm started grinning and chuckling and his mood took a dramatic turn. “Finally something’s coming up for us! I will have to congratulate that ridiculous man once he returns. He seems to be the only one of my subordinates who can follow my plans and not screw everything up. I might not even court martial him for this one.”

Fruehauf smiled outwardly and sighed internally. “If you say so sir.”

At the end of the room, Marie, one of the radio operators, a plump girl with short blonde hair, raised her hand and urged Fruehauf over. She had been tasked with external communications duty – keeping track of the units that followed behind the Vorkämpfer’s front line – and had spent much of the day monitoring the lines to HQ and Supply and to the divisions outside of Bada Aso, who had little to say with regard to the current offensive.

Fruehauf unplugged her handset from Erika’s radio and plugged it into Marie’s.

Many of the external divisions whiled away the opening days of the occupation by doing manual labor, pitching tents, repairing buildings that could be used as headquarters, rounding up Ayvartan prisoners behind the lines, dealing with unruly villagers who clung on to the hope of rescue, and confiscating valuables the army could use. They were in short playing the role of cleanup crews lagging behind the blitzkrieg. Most of the officers in the Vorkämpfer had a low opinion of those units that stayed behind, but not every military asset could move fast enough to join the Bada Aso offensive.

Particularly the more esoteric intelligence personnel.

Such as, in this particular instance, the weather battalion.

Freuhauf listened with growing alarm, and then called out to the General.

“Sir, the storm is growing worse, we have to evacuate the Umaiha district ASAP!”

Umaiha Riverside – Old Police Station

Gunfire in the immediate area rattled Madiha awake and forced her to feign sleep.

From the corner of a half-open eye she saw a figure in a black coat and hat, surrounded by four figures in beige uniforms, move in from across the room with rifles drawn. Sgt. Agni dropped her pistol and raised her hands in surrender. In the distance she heard gunfire, both automatic bursts and the snaps of rifles, so resistance had not been entirely annihilated.

Madiha surreptitiously tested her arms and legs – and found she could move.

“My name is Gaul Von Drachen. Surrender immediately,” said the man in the coat.

Sgt. Agni offered no reply.

Her eyes wandered, looking toward the ground. Madiha could not see them, but one of their comrades had probably been shot dead near her as the men entered the room. Since the police station was near the bridge, it was a natural hiding spot for any gun battle in the adjacent street – and a natural staging area. Certainly these men had broken from the larger fight outside, hoping to end it quickly, but that meant it was not yet over.

“I see no value in doing that at the moment.” Sgt. Agni nonchalantly replied.

The Cissean officer, Von Drachen, shot his pistol at the floor several times, each time hitting Agni’s pistol and launching it further and further from her. He reloaded, and then, speaking Ayvartan eloquently and fluently, he pressed Agni for a surrender once again.

“Hail your units on the radio and order a surrender. We can end this bloodshed immediately or I can crush you with my artillery as I have been doing for the past several hours. It was easy to see that your objective was to prevent me from entering the station, and that mission has miserably failed. I am here – hail them and tell them to stop.”

At the officer’s side, one of the men finally examined the room and found Madiha.

“General, hay otra mujer recostada en las piedras–”

Blood drew from the man’s neck as a revolver bullet ripped through his throat.

Von Drachen and his subordinates had scarcely turned their guns to acknowledge the pile of rubble in the center of the room, and Madiha sat up, sidearm drawn, both hands on the handle. In blinding quick succession she continued to shoot. As the man fell, clutching his neck, Madiha put a bullet between a pair of eyeballs, and into a gaping open mouth, and through the bridge of a thick nose. Her final bullet blasted Von Drachen’s pistol out of his hand. It hit the floor with the rest – his team collapsed in two heaps around him.

Stunned, he raised his hands as Madiha rose to her knees. She felt a little weight as she tried to stand, but the lag was over in seconds. Adrenaline kept her going strong.

She was out of rounds but she kept the Cissean officer in her sights nonetheless.

“That certainly was some impossible shooting.” He said.

“I don’t miss.” Madiha replied. Her words came to her precisely. Her mind was clear.

“By any chance are you the actual officer in charge?” Von Drachen asked.

“I’m just Sergeant Nakar.” Madiha said. He did not need to know her real rank, and she did not make a habit of wearing her pins and insignia. “How about you surrender now?”

“Oh, I don’t see any value in doing that.”

He reached into his long, flapping coat and with a sudden flourish Von Drachen brazenly hurled himself toward Madiha. She dropped her gun, drew her combat knife and intercepted Drachen’s draw – she had expected a knife or a bayonet to come out from under his coat and was shocked to see a an actual sword clash against her knife instead.

It had a brilliant blade and fine etchings.

The officer’s sword had enough handle that he could push against her with the strength of both his hands. Madiha reacted by supporting her knife hand with her free hand, but she was buckling against Von Drachen’s sword, and the edge was pressing against her gloves. She could feel the pressure of the metal against the side of her hand as they struggled.

“I absolutely hate this sort of thing, it will end badly for both of us; what say you we just pick up our guns and fight like civilized human beings do?” Von Drachen asked.

Madiha grinned at him. “I’m perfectly fine with this. I don’t miss with a knife either.”

She pushed back against the sword with both of her hands, and momentarily lifted the blade and broke the clash, creating enough room to step back. Von Drachen recovered fast and swung wide against her; she leaped further back from him, raised her hand back over her shoulder and then threw her knife in a quick whipping motion. She put the blade solidly through Drachen’s coat, stabbing the knife through his shoulder.

He grit his teeth and cried out.

But his grip on the sword did not loosen and his stance was not even shaken.

Now it was his turn to grin. “You don’t miss, but you really don’t want to kill me, do you? Gambling on a prisoner when you could have had a kill seems unwise to me.”

Von Drachen drew the knife from his flesh, turned and threw it in one fluid motion.

Across the room Sergeant Agni cried out, falling to the ground several meters away from her pistol as the knife struck her leg. Madiha was shocked, she had completely forgotten Sgt. Agni in the midst of the fight. She broke from the fight to help her.

Von Drachen threw himself forward, heaved his blade and swung again.

His cutting edge soared over Madiha as she ducked and rolled off the rubble.

She broke into a run for the other side of the room with Von Drachen in pursuit.

“Agni, don’t move!” She cried out, but the Sergeant signaled for her to halt.

“Forget the pistol Madiha, use this instead!” Agni shouted.

Sgt. Agni cast something, sliding it along the ground – a machete from her tools.

Madiha stopped the weapon with the tip of her boot and swiftly kicked it up to her hand. She caught it in time to intercept another one of Von Drachen’s blows; edge met edge. Madiha started turning back his attacks with one hand, the butchering edge of her machete bashing back the refined blade of the officer’s sword. Von Drachen started to tighten his swings and he stepped back with every exchange, likely in fear of Madiha trapping his blade. She could easily take off a few fingers in a clash if he closed with her too recklessly.

Edge continued to meet edge, metal at the tip of metal, glinting in the gloom and rain.

Step by step they made it back almost to the center of the room.

Von Drachen stepped back to the place Madiha had been trapped in, and she let him create distance. Catching their breath after their vicious clashes, all too aware now of the danger they posed to one another, the combatants circled and waited.

Madiha gripped hard her machete. She could feel it in her hand, its weight, the way it interacted with the air, the subtle pull of the earth as it moved. She knew it perfectly.

They exchanged spots; circling, Madiha stepped in the ring of rubble and Von Drachen off it, each holding up a blade and keeping a free hand. For several minutes it seemed they only stared. Neither could count quite count on any more backup – and both could tell as much from the actions of the other. This pile of rubble might just be a tomb for one of them.

Von Drachen smiled. “Nocht is a cesspit of arrogance and ignorance, so it’s hard for me to convince you to surrender to them and guarantee it will be a step up. However, I would like to impress upon you, that if you surrendered, it would be very helpful to me.”

Madiha did not look at his face. She looked over his arms, his legs, and his weapon.

In her mind all of the mathematics played out perfectly. Every centimeter of muscle on her body, every nerve fiber, readied itself to move in whatever way suited the long knife.

She could fight with the machete even though she never once practiced it.

This did not feel alien or frightening anymore. It just felt like something she did.

To her it was just like a gun. Any weapon worked for her ability. She might not be able to shoot Von Drachen unfailingly but she knew how to skillfully counteract him. He would try to stab or cut her arms if he wanted to capture her, which she was almost certain he would want to. She would try to do the same. She definitely wanted him in shackles.

Physically they were nearly evenly matched.

Madiha was as tall as he, and they were both lean and fairly muscular for their frames. Madiha appeared a little smaller, but Von Drachen was probably similar once his big coat and tall boots came off him. She felt confident, and made the first move, tentatively swiping at the edge of his blade. Von Drachen stepped back, avoiding the glinting metal swipe in the gloom of their arena. At first he raised his sword to guard, but as they backed off out of each other’s reach again he lowered the weapon to his side and became more relaxed.

“When I took this sword I thought it would make things easier for me, but suddenly it has made them all the harder. This such a regrettable situation.” Von Drachen said.

“Believe me, there’s other things I’d rather be doing.” Madiha replied.

Movement; her eyes darted to Von Drachen’s feet and back up, and she held her machete out for a block as he threw himself forward again; she met his blade, the metal scraped, but there was no strength from Von Drachen’s end.

Rather than clash he allowed himself to be brushed aside.

He used the impetus to step away, past her, onto the remains of the roof slab.

He had drawn a radio from his coat.

“Artilleria pesada a las coordenadas–”

Madiha turned and approached.

For each step she took Von Drachen backed hastily away, speaking Cissean into the radio. It was a short conversation – barely a few seconds later he stopped speaking abruptly, sighed and threw his radio over his shoulder, smashing it on the wall behind him.

“Just my luck; out of HE shells.” He said, a childish, exaggerated frown on his face.

Von Drachen charged down from the slab, raised his sword and brought it down over Madiha as if to batter her down; with one hand she caught the blade and with the other she swung her blade right into his own weapon and hacked it apart. Her machete went through Von Drachen’s sword, taking a dull half in her hand and leaving half in his.

And the blade barely managed to scuff her glove in the act. It had no real edge.

“Hit me with a sword enough times and I can tell if it’s a toy or not.” Madiha said. She dropped the chunk of the sword that she had caught to the floor, and stepped on it.

Von Drachen backed away from her, holding the remaining bit of his blade.

He shifted his feet, bent his shoulders, and held out the broken blade like a fencer.

“You cannot be serious.” Madiha said. She was becoming exasperated with him.

“En guarde, Sergeant!” Von Drachen said, twisting his wrist and blade with a flourish.

Now it was Madiha’s turn to rush. But Von Drachen jabbed the air with his jagged dagger as Madiha charged him. She twisted away from his thrust, and put the resulting momentum into an attack on his flank. With her fist and the handle of her machete she struck the side of his head. He staggered back, dazed by the blunt blow.

Madiha flicked her wrist and held the machete by its blunt blade end, wielding it like a club. Sensing an opportunity to end the struggle she advanced on him.

He recovered in time to strike first, and swiftly kicked her feet out from under her.

Madiha fell back, and Von Drachen reversed his own dagger and loomed over her.

He raised his hand, blade to the floor, ready to drive through her flesh.

But as he closed in to stab her Madiha gathered all her strength and in a sudden motion propelled herself from the ground and on her feet. She timed it just right; her head and Von Drachen’s met halfway, and he staggered back and away from the collision, his nose broken open. She was not unharmed either. Blood rushed from her forehead, and her vision momentarily swam. She struggled to remain standing and her machete shook in her hand.

Von Drachen stumbled and stepped as though drunk. But he was laughing all the while.

“Sergeant, you rascal. I’m starting to think you’re more than you claim.” He said, clutching his face. He was bleeding profusely from his nostrils, and his temple was badly bruised. Despite these injuries he did not seem to slow down. He straightened out again and stowed the remains of the sword into its scabbard. He then held up his fists like a boxer.

He took a few weak jabs into the air, and locked his eyes to Madiha.

Madiha raised her eyebrows, and with them, her machete, ready for another round. She was growing tired – she would have to kill Von Drachen if this did not subdue him.

Abruptly, Von Drachen straightened out, loosening his guard and lowering his fists.

“It appears I successfully stalled for time. I am now going to extricate myself from this before any more of me is cut up. Sorry, Sergeant, or should I say, Major.” He said jovially.

Behind him a shell penetrated the hole in the roof and crashed where Madiha had once lain. She reflexively shielded her eyes, but the shell explosion cast little heat and no light.