This chapter contains scenes of violence and death.

29th of the Aster’s Gloom, 2030 D.C.E

Adjar Dominance, City of Bada Aso – Ox FOB “Madiha’s House”

As far as the eye could see clouds over Bada Aso had become a continuous grey sheet, so still and unbroken they perfectly supplanted the sky. In the morning even the drizzling rains had subsided. Through the office window Parinita saw the breakfast line forming across the street. It was a scene as if from a gentler time.

People passing around metal platters down the line, singing songs while waiting for their lentils and flatbread, for their curry and fresh fruit juice.

Then a tank drove down the street and everyone in the line waved at the commander half-out of his turret, and he waved half-heartedly back as he headed out on armed patrol.

Work had commenced on sandbag redoubts to block out the road south of the FOB. Parinita saw a light staff car towing a 45mm gun into place behind a half-circle sandbag wall, and several volunteers in jackets and overalls, and even a few women in dresses, at work heaving bags and piling them up, pulling machine guns out of the buildings where they had been hidden and rolling them out, bringing ammunition from concealed stocks.

For moment, Parinita could just look at the breakfast line and ignore the war. She could focus on cheerful volunteers until her eyes seemed to cross and her vision became blurry.

She pulled down the window shutters and returned to the desk, licking the tip of her finger before opening a folder of reconnaissance reports, including aerial photographs taken by a biplane early in the morning. Due to their relatively silent engines, the obsolete Anka still found a use in Bada Aso – they had performed some limited late night bombing and early morning photography, surprising the enemy and avoiding engagements.

They had to plan these flights ahead of time, because the airport at Bada Aso was unusable, and because the overwhelming majority of the Ox air force and air bases had been destroyed, abandoned or evacuated since the first days of the war.

Battlegroup Ram in Tambwe had graciously allowed them to use its border air fields to land and scramble planes, but was redeploying its own planes farther north.

Still, they did their best with what few planes and what little runway they could get.

In her hands she held photos of Umaiha’s streets, still waterlogged, the river itself choked with debris swept into the water from the streets, and from buildings overtaken by the growing ferocity of the stormy waters.

They were still gauging the extent of the destruction there.

By current counts, the 28th, in its various and deadly ways, had caused at least 8,000 casualties for the Ayvartans, the overwhelming majority incurred in Umaiha. Not only did they lose the defensive lines, they lost peripheral patrols, mobile reserve groups, civilian volunteer laborers, logistics personnel, and rescue workers and crisis assessment troops.

So wide-ranging, sudden, and devastating had been the flooding, the rain, the lightning, the storm winds, that it seemed as though the entire southeast was smashed off the map.

Parinita put down the photos and read the early reports and turned over in her head what her own conclusive report on them would say. Her Commander would certainly desire a full account of the weather and its effects, as well as losses across the actions of the 28th.

She could say definitively that the 1st and 2nd Line Corps were no more.

Anyone who could still fight joined the 3rd and 4th Line Corps in preparing for the coming assault on the central district. Luckily for them, Nocht had been caught up in the weather themselves, and suffered losses of materiel in Penance that would surely give them some pause. She hoped they would have a day or two to reorganize before the next operation. That was the situation she saw looking over the documents in her hand.

She would have to wait for the Commander’s word before thinking over it anymore.

Thankfully, the Major was safe and relatively unhurt for what she had suffered.

On the floor of the office, Madiha slept soundly on a mattress, dug out from the ruins of a nearby apartment building. She was covered in curtains and towels in lieu of blankets – they were running low on warm blankets, an item often unnecessary in the Adjar dominance that was therefore not often kept in good supply. Madiha had a medical patch on her forehead, under her black, uneven bags. She slept, eerily peaceful.

Parinita had thrown herself in her arms the moment she saw her last night.

It became clear to her then she wanted to be closer to Madiha.

She was special to her. She wanted to properly know her as more than just a comrade in arms. These desires had slowly built and it was time to recognize them.

But still, she felt awkward about it. She couldn’t act on it. But it was fine.

For now it was enough to be in this office. It gave her purpose.

She could wait for the rest.

There was a knocking on wood that brought her out of her contemplation.

She looked over.

Behind her the door opened, and Bhishma, head of her staff, stepped through the door with a plate of food and a mug of tea. He had brought her a steel mug full of lentils, a stack of flatbreads, and sweet Halva made from semolina and tinged red with berries.

“What a pleasant surprise!” Parinita said, clapping her hands. “Thank you, Bhishma.”

He smiled. Bhishma was a dark-skinned young man with frizzy hair and an orderly appearance. They had worked together for years now; normally he was quiet and diligent, but today he looked energized. “It’s nothin’ ma’am. I thought of how hard you’ve been working and I figured you wouldn’t be going to join the line, so I got a little extra for you.”

“Nothing for the Commander, though? She has also been working quite hard also.”

Bhishma had no answer to this.

His cheeks turned a little pink, and he scratched his hair.

Parinita smiled and waved her hand as though trying to fan away his concerns with the air. “It’s ok, don’t worry about it! I’ll share with her. We can have a proper meal at lunch.”

Bhishma bowed his head and retreated uneasily out the door. Parinita sighed a little.

As the door closed, she heard a yawn and a sleepy muttering. “What was that about?”

Madiha sat slowly up against the office wall and stretched her arms overhead.

“I may be wrong but I think Bhishma was trying to curry favor.” Parinita said amicably.

“Was he successful?” Madiha said through another yawn, having fully stretched.

“Nope.” Parinita smiled. “Are you feeling alright, Madiha? Our medics are worried.”

“I feel like I’ve been tied in a knot, and my forehead feels split open.” She paused, and then sneezed. She wiped her nose on her sleeve. “And I think I’m going to be sick.”

“Judging by your conversational tone, you don’t seem too concerned.” Parinita replied.

“I’m not concerned, to be honest.” Madiha said. “I’m just glad to be back at my house.”

“I am glad you are well.” Parinita said.

She held back her emotions – she almost felt like crying, she was so happy to see the Commander again. Madiha would not have minded. She had already cried on her shoulder last night. But she wanted to give the Commander some peace and a chance to relax. She deserved warmth and ease. “We should take it slow today. You’re still recovering. I wouldn’t want you to become ill. We can go over the current events at our leisure.”

“I do want to rest a little, but I have a few orders to give.” Madiha said. She lay back against the wall with her arms behind her head. “First; Parinita, I wanted to thank you.”

“I don’t believe I’ve done anything worthy of much thanks.” Parinita demurely replied.

After all, she was just herself; what could she possibly do or add?

“No, you have; you’ve stayed by my side. I’ve been acting foolish. I lost sight of so much, both about myself, and you and our comrades. I should have listened. Despite everything that has happened you are here again, as warmly as you have always treated me. I want you to know that my eyes are open now, and that I have regained my resolve.”

Parinita felt blood rushing up to her face and ears.

“I am very happy to hear that, Madiha.” She stammered.

“I have treated you poorly; and I took in vain the courage of our comrades who are fighting. From now on, I want to be the Commander you and them deserve.”

Madiha stood up from the ground and patted off the fibers from the curtains and towels that had collected on her jacket and pants. She had been given a fresh uniform when they brought her into the HQ last night, and thankfully she had not been wearing her pins and medals, or they would have gotten wet or lost. Parinita kept them in a case in their desk.

“In my eyes you have always been more than worthy, Madiha; but I’m glad for you nonetheless. I hope to continue to serve you in the same capacity as before.”

Parinita was cloaking it professionally, but she wanted to bolt up and embrace her.

“I won’t have it any other way, Parinita. I want us to face this together.” Madiha said.

Now that Madiha was wider awake, Parinita spotted a few small wisps of the old flame trailing from her eyes, like a lamplight through fleshy glass. She was surprised. The burning was not as bad as it had been yesterday. Had she shed it? If so, her soul was safe for now. But her earthly condition was definitely deteriorated. She looked tense and exhausted, and she was definitely shaking a little. Hours out in the cold, and physical wounds left open and bleeding throughout. It was a wonder she was walking around at all right now.

“You should reconsider it if you’re keen on running around.” Parinita cautioned her.

Madiha nodded. She rubbed a hand along her back. “I feel a little stiff, but I’ll be fine.”

Seeing her like that, Parinita summoned up her courage. She knew she could do more.

“Then let me help you with your pain, please sit,” Parinita said, pointing to a chair across the desk. She raised her hands and curled the fingers to demonstrate. “I know a little trick that might help you stand up straighter than before, if you’ll indulge me.”

It was a little embarrassing to say, but she managed to retain her composure.

Without question, the slightly bleary-eyed Madiha pulled up the chair and sat down. She was compliant, and perhaps she knew what Parinita meant by the gestures she made.

“My grandmother and mother were healers, and they taught me a lot of things.”

Smiling and cheerful, Parinita stood up from behind the desk and walked over to her.

“Face away,” Parinita said, tapping with the tips of her fingers on Madiha’s shoulder.

Nodding, the Commander turned the seat around, turning her back to Parinita.

Parinita reached around Madiha’s chest, slowly unbuttoning her jacket.

She felt Madiha tense up at first, but whispered in her ear to relax. She pulled the woman’s jacket off, and then the dress shirt and tie under it after that. Beneath the uniform the Major wore a banian, a tanktop style undershirt tight against the skin.

Parinita looked her over. Madiha had great shoulders, fairly broad and lean with some definition. Her arms and back drew her attention too. She was slender, somewhat flat-hipped, with a small bust, but tall and lean and smooth. Parinita felt a twinge of attraction.

Blood rushed to her face as she realized where her thoughts led her.

She almost felt guilty for ogling; that was part of what turned her off the practice at first. To massage, one had to touch, and it felt too intimate an experience.

And yet, though she had not performed the arts in years, Parinita felt surprisingly confident in her ability. She felt the muscle memory returning. Her grandmother had taught her, showing her drawings of the chakras, charts of muscle groups, demonstrating the pliability of skin and flesh on the clients who came in. When her mother deigned to be around, she took shared some casual insights, though hers were much more lascivious.

Parinita, when she was a child and then a teenager, felt theirs was an indecent practice overall. Now she felt excited, felt a brimming in her hands, as if discovering magic. Her hands felt as if they were meant to soothe, to ease pain, to disperse those agonizing flames.

She patted across Madiha’s shoulder, touching the muscle, and felt girlish and giddy.

“Major, what kind of military planning gets a girl shoulders like this?” She said.

Madiha laughed. “All the hours I spent exercising. I was bored out of my skull while nothing was happening. I spent most of my tours doing pull-ups off the low roof of a clay hut out behind the FOB. I used to be a little bit bigger; I do not exercise as much anymore.”

“I do prefer you this way; you have a great balance of elegance and strength. I guess in comparison I’m a bit sedentary,” Parinita chuckled, “but I do like to run. I used to run a lot. But that has made me nowhere near as gallant as you are, if I might venture to say.”

“I think you look perfectly proportional.” Madiha said. Her breathing quickened as Parinita’s hands settled upon her, and began to prod and press across the bare flesh.

“Perfectly proportional? I suppose that’s a compliment.” Parinita giggled.

Her fingers rose up to Madiha’s slender neck, and she felt the Major’s pulse, quickening with a rush of warm blood. Her hands glided up, lifting tufts of dark hair. It was soft, straight and mostly symmetrical; it framed her face well. She guided her fingers over the woman’s smooth forehead, covered by a thin medical patch to help her heal; she slid her palms across Madiha’s gentle cheeks and jaw, just feeling the warm brown skin; the smooth, gentle bridge and thin nose; the soft lips, breathing irregularly from the touch.

She closed her eyes, and she felt like Madiha’s warmth was entering through her hands, that their pulse was becoming one, echoing across flesh. It was a blueprint for Madiha’s body. Textures and contours and sinews, carrying a picture, as if Parinita had her own form of radar. From what she touched, she felt like she knew everything about Madiha’s body.

She opened her eyes and briefly lifted her hands from Madiha to feel empty air again.

All of the flame vanished; the metaphysical pain gone, Parinita could focus on the rest.

“You’re really tense, Major.” Parinita said, giggling. “I should have done this sooner.”

Madiha nodded. “I think I know what this is. It’s called Maalish, right? Healing hands.”

“I would view the healing part with suspicion.” Parinita said. “It’s a source of relief.”

She pulled Madiha’s banian up from over her back and pressed her hands against the woman’s skin bare skin. Carefully and gently she glided the soft tips of her fingers down the Major’s smooth, baked brown shoulder-blades. Madiha made a little noise.

“Oh, is it rough?” Parinita asked.

“No,” Madiha said. Her voice stammered. “It’s softer than I’ve ever felt.”

Exhilarated by the answer, Parinita applied pressure to the tissues, finding areas that were hard and tense and working them, kneading them, pulling and prodding them like clay. She felt the flesh budge under her fingers. She received feedback from Madiha’s body, gentle shivers and soft moans and the pulse just beneath the skin, and she accounted for it.

Parinita gave herself up to these sensations, intrigued by the subtle drumbeat that was punctuating the moment. Slowly the motion of her wrists, of the heel of her hand and the base of her thumb, the grasping of fingers, all of it quickened.

Madiha started to rock a little in her seat in response.

Parinita started to work down from the shoulder, slipping her fingers underneath Madiha’s arms, gripping her upper flanks, the side of the breasts, and working the ribs and scapula with her fingers and thumbs at once. Her hands were moving to a rhythm set by Madiha’s breathing and pulse and the pliability of the skin and the knots of muscle. It was like a dance between them, and it brought Parinita a surge of reassuring, powerful emotion.

Smiling, she leaned her head on Madiha’s shoulder. “Is it working, do you think?” She squeezed on Madiha’s flesh a little more, and saw her jaw loosen, and her lips curl with a little gasp. Heat from her body transferred delectably to the tips of Parinita’s fingers.

“It’s doing something.” Madiha said, her eyes closed, her mouth hanging a little open.

Parinita lifted her head, and raised her hands up over Madiha’s shoulders, kneading the woman’s trapezius with the base of her thumb. Madiha let out a little groan. To see someone’s body respond to touch, to feel their flesh relax, to hear them grow content; it was a primal communication so different than the bitter, clinical things Parinita had been taught.

“Spirits praise,” Madiha said, gasping, “this is far different than I ever imagined.”

Almost with a snap, Parinita put sudden, final pressure on Madiha with all of her fingers, pressing on her neck and shoulder until she heard a subtle crack. Madiha arched her back. She was loose, relaxed; as if all of her flesh had gone limp in Parinita’s hands.

Under her touch, Madiha lay back against the chair, panting, contented.

She raised her head, staring up at Parinita. She smiled, breathing in short gasps.

Madiha caught her breath.

“I never believed in this sort of thing, but I’m a convert now.”

She gripped her own shoulder and moved her arm. She stood and walked around the office for a moment. Her movements were a lot more fluid and energetic, more liberated.

“It’s not magic or anything,” Parinita said modestly, “it just takes some dexterity.”

“I feel so much better; it’s amazing.” Madiha said. She was giggling like a girl.

Parinita blushed. “Now, now; you’re not just faking it to make me feel good, are you?”

“Of course not Parinita; you have a gift with those hands of yours.” Madiha said.

She took Parinita’s hands into her own with almost childish enthusiasm and pressed against her palms with the tips of her own fingers. Parinita grew redder. Her face was almost the same flushed color of her hair, and her lips hung open without words to say.

Perhaps recognizing her sudden gregarious turn, Madiha awkwardly released her.

“Ah, sorry, that was a little untoward. But it’s been a long time since I felt so refreshed.”

“I’m glad.” Parinita said. “My mother used to say that Maalish also soothes the soul.”

“I know.” Madiha said. She smiled softly. “You have been doing a lot of that lately.”

Parinita’s eyes spread wide open. Did she know about the flames, about her eyes?

“I’m sorry.” Parinita said sheepishly. “Madiha, there’s something we should discuss–”

“You’ve nothing to be sorry for. I have my own confessions to make too. We’ll talk about that later. For now, let us focus on the material, and don’t worry about the rest.”

Madiha’s eyes glinted with a hint of fire, and a sharp red ring glowed around her iris.

Parinita saw it – and it was a different fire. Madiha was making sure she could see it.

Nonchalantly the Major dressed again in her shirt and jacket. She walked around, patting Parinita jovially in the back, and sat behind her own desk, adjusting the office chair for her height. She brought out her pins and medals and began to attach them to her uniform in their places. Finally, she collected a stack of papers, looked at them and dropped them.

“I don’t know what any of these are about, goodness; also, I’ll be needing a new pistol.”

Any tension in the room suddenly diffused. Back to work; Parinita grinned and nodded.

“I’ll get you a new pistol, but you need to promise to take good care of this one.”

Madiha raised her arm as if to swear an oath, and held her fist over her breast.

Parinita laughed girlishly at the gesture. Thank everything; Madiha was still alive.

“Say, do you want some halva, Major Madiha Nakar? They put berries in it today.”

Madiha looked at the plate on her desk. “I’d be delighted, C.W.O. Parinita Maharani.”

30th of the Aster’s Gloom, 2030 D.C.E.

City of Bada Aso – Outskirts, 1st Vorkämpfer Headquarters

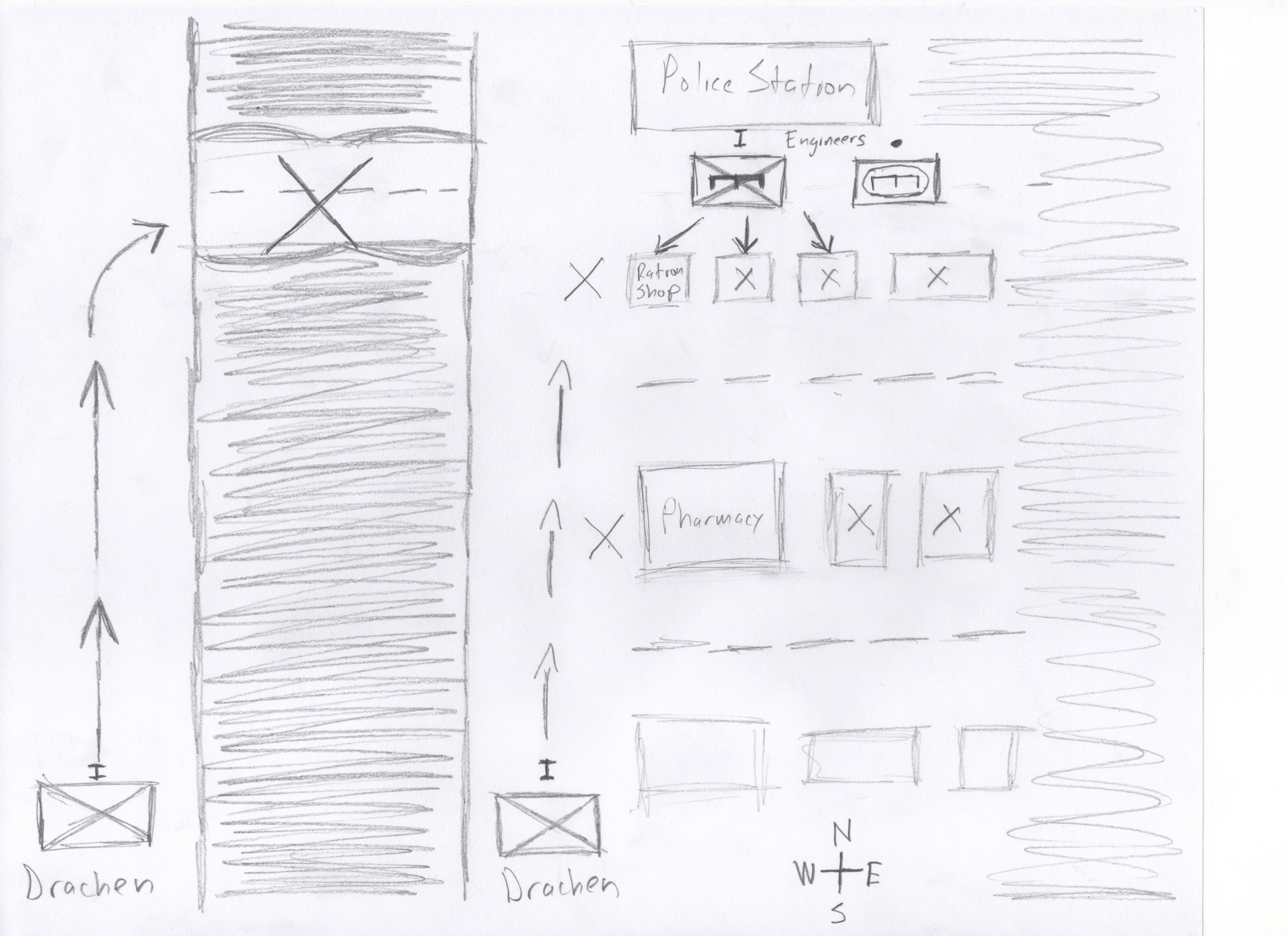

Outside Bada Aso a Nochtish truck convoy halted off the road after almost a week’s worth of uninterrupted driving. One vehicle had broken down due to a lack of oiling. Horse wagons were dispatched from the Headquarters inside the city and the cargo was loaded on them. At around noon, the equipment was unloaded at the HQ and installed by engineers overseen by Fruehauf. They spent about an hour working with cables and vacuum tubes.

Finally, a telephone was installed in the Vorkämpfer HQ. Line operation was overseen through the Ayvartan cables and headquartered in the occupied city of Dori Dobo near the border to Cissea. Fruehauf informed Von Sturm about the successful installation. She was excited about having a phone. It was a cute, homey kind of object. After all, she used to be a telephone girl before she joined the army. Von Sturm did not share her enthusiasm at all.

The 30th of the Aster’s Gloom saw the first international phone call between Ayvarta and the Nocht Federation. From occupied Bada Aso, the single telephone line out to Dori Dobo carried a call request that was manually forwarded through three boards in Cissea, until it reached the first trans-oceanic radio-telephone station in the northern coast of Cissea. Through the airwaves the call crossed the sea. Upon reaching The Federation of Northern States, it was forwarded to its destination in the Nocht Citadel, where it was picked up.

One hour of routing, waiting, and growing, sinking dread in Von Sturm’s stomach.

Finally, the call was put through. Von Sturm tremulously raised the handset to his ear.

“I love the telephone, don’t you, Anton?” President Lehner said. “Love the telephone. I’m a man of technology, Anton. I want no barriers between human hands and scientific achievement. Today, we’re making history! And oh, it couldn’t have come a better time. I’ve been waiting so long to express my disappointment. Thank the Messiah for these lines.”

“Yes sir.” Von Sturm replied. He seemed to struggle to keep his teeth from chattering.

“Let us talk, Anton. Let us talk, primarily, about my disappointment. Once you understand the depths of my disappointment, we can talk about what comes next. Did you know that Dreschner took Knyskna? Dreschner is on time. I like Dreschner; honestly, I am fond of all my personnel, Anton. And that is why this hurts. Disappointment hurts.”

Fruehauf watched on innocently, smiling at the presence of a cute little dial telephone in the HQ’s second floor, while President Lehner coolly dismantled and berated Von Sturm.

Thirty minutes later the pair reconvened with the rest of the staff downstairs.

Von Sturm’s eyes seemed permanently forced open, and he walked stiffly.

Fruehauf whistled and skipped and wondered if she might be able to organize calls to home from Ayvarta on the radio-telephone. She was in love with the little thing.

Down in the restaurant dining area, Von Drachen waited on one of the tables. He had a thick bandage over his forehead, gauze over his nose, his arm in a sling and patches over his shoulder, easily seen under his dress shirt. He wore his jacket still, but with his arms out of the sleeves. Von Sturm sat across the table, holding his head up by his hands.

“Oh good, I’m glad you’re here.” Von Drachen said. “I’ve been rehearsing this speech I wanted to give to someone. My mind is bursting with ideas after the battles of the 28th.”

“Are you sure that’s not a result of having your forehead broken?” Fruehauf asked.

“It might be, but in that case, it is a good result.” Von Drachen said, shrugging.

“I was just joking. But I guess I’ll accept that response.” Fruehauf sighed.

“I’m listening.” Von Sturm said sullenly.

He looked at Von Drachen over steepled fingers.

Von Drachen’s face lit up.

Afforded the chance to speak, he stood and backed away from the table, and spread his good arm as if to gesture for the attention of a crowd. Fruehauf and a few of her radio crew, on their breaks, turned around to watch. Von Drachen cleared his throat, and he swept his hand slowly in front of himself, and began to speak in a serious voice.

“Prior to to this conflict all of our battles have been against forces in underdeveloped, broad, open areas. Cissean villages, Bakorean fields, and Ayvarta’s grasslands afforded us the ability to bring our superior firepower to bear on the enemy. Exposed enemies would be rushed and obliterated. Enemy strongholds were few and far between and we could seize them or bypass them at our leisure. If they moved against us, they were destroyed, and if they failed to move, they were encircled. We dictated the terms of any engagement.”

Von Sturm was dejected throughout. Von Drachen continued without skipping a beat.

“Bada Aso is a large, fairly tight, conventional city. It restricts our movement, our lines of sight, and it prevents us from concentrating our forces – how many men and tanks can you feasibly cram into a street before you have a slow-moving soup kitchen line in uniform?” Von Drachen smiled in the middle of his explanation, as though he was overjoyed by the works of his enemy. “And the Ayvartans have used these conditions expertly. Their equipment and training is meager compared to ours, but they have been organized to take the fullest advantage of this uncertain environment around us. They have created a situation where we will bleed men fighting them, bleed men scouting them and bleed men bypassing them. It’s like fighting in hell, it’s like a medieval engagement! We cannot look at this using our ordinary strategies. It might even be best that we do not move at all for now. We must be more meticulous, Anton Von Sturm, or else we will–”

“But we have to move!” Von Sturm shouted, interrupting him. “How the hell does it make sense that with worse equipment and poorer training they can successfully slow us down! Just because they have holes to crawl into? Tunnels to squirm and crawl around?”

“Because they know what’s around every corner of this city and we don’t.” Von Drachen said. “They can see through the stones and we can’t. We think we have the initiative because we are the ones launching attacks, but they are the ones who dictate every engagement because they have tactical control in every situation. They can retreat when they want, counter when they want, and lay whatever traps they want. It is they who have the initiative despite not attacking. It’s simply fascinating, don’t you think?”

“It makes no sense.” Von Sturm shook his head. “It is absolute madness to think that.”

“They have preyed on our superior position.” Von Drachen said. “Our entire army was built and trained to punch through defenses with overwhelming power, and then break into a marathon run toward new objectives. But we can’t run in Bada Aso: we keep slipping and hurting ourselves on the concrete with this vaunted ‘overwhelimg power’ of ours.”

Von Sturm pushed back his chair and stormed from the table, rubbing his forehead in consternation. Fruehauf and Von Drachen looked on, until he had disappeared upstairs.

“Was it something I said?” Von Drachen asked. “It’s just my opinion on things.”

Central District FOB, “Madiha’s House”

After days of tinkering, a silent breakthrough occurred.

In the basement of the school building an engineer finally found a compatible vacuum tube for the old long-range radio, and quietly he installed the tube in the correct slot and tested the device. There were no sparks and he picked up a signal. He left it at that.

In his maintenance report, “potentially” fixing the radio telephone was the last item, behind adjusting an office chair, checking the air circulator and fixing a hallway light.

Hours later an alien sound echoed across the halls of the FOB – the radio telephone was ringing. On the first floor of the FOB the switchboard operator, stationed in front of the obsolescent radio-telephone monitoring equipment, awoke in a puddle of her own saliva. She scrambled to connect the call, having forgotten most of the controls.

She had been almost sure she would never have to use the device.

After a moment’s panic she managed to connect the incoming call through to to C.W.O Parinita Maharani in the Major’s office, who was just as puzzled by the communique as anyone else. With Madiha watching behind her, she picked up the handset.

Parinita listened to the call carefully. At the other end, the KVW radio operator read several press-worthy statements – confirmation that Solstice had been brought around to Madiha’s plan for the city, on the condition that she evacuate by sea to Tambwe, as well as offering assurances that the end was in sight for the political deadlock of the Socialist Dominances of Solstice. Parinita was optimistic about the call and glad to receive it. She told Madiha the gist of everything. Knyskna had fallen, but there was good news too.

Madiha was less optimistic. “Useless,” was one of her choice words about the call.

Regardless, they both agreed it was time to start putting into motion the end of Hellfire.

Then, another alien sound, same as before.

It was the radio-telephone again. Once more the operator was in an anxious and manic state, and this time she forwarded the call directly to Major Nakar instead of Parinita. For her part, the Major did not know whether to think this ominous or auspicious.

She picked up the handset and raised it to her head. “This is Major Nakar.” She said.

“Major, congratulations on your recent victories. You are a beacon in this darkness.”

Madiha felt a thrill down her spine.

Her eyes widened. Parinita stared, and silently tried to ask what was wrong. She received no answer. Madiha recognized the voice – it was the Warden of the KVW and head of the Military Council, Daksha Kansal. She was once the voice and face of their revolution – though sidelined by the petty politics of the council she had been instrumental in fomenting the unrest, seeding the ideologies, and supplying the strategies to overthrow the Empire. She was in a sense Madiha’s boss, but they hadn’t spoken for many years.

“I,” Madiha hesitated for a moment, but found words quicker than she would have before recent events, “I am grateful for the kind words, Warden. However I would be hesitant to refer to anything occurring in this city as a victory. As I communicated to the esteemed Admiral via our offices, this is not a battle that I plan to win in the strictest sense.”

“Yes, of course. I recall your plan and continue to support it. But you humble yourself; with Gowon’s leadership this entire operation would have been impossible.” Kansal said. “Gowon would have been intimidated by Nocht’s strength. You confronted them.”

“Thank you for your confidence. To what do I owe this rare call?” Madiha asked.

“Regrettably rare; but I hope to take a more active role in our operations from here on.” Kansal said. She paused for a second before continuing to speak in a strong tone.

“Major, you have been informed that there are strides being made here in Solstice to support the war. I have committed to sending special trains from Tambwe to evacuate your wounded. Support from Ram will be available as well if you think it would be warranted.”

“I do not.” Madiha said. “Ram should remain put and fortify the border to Tambwe.”

“I expected you would say that.” Kansal replied. “You were always putting other people ahead of yourself. I am happy to see that. I should leave you to conduct your strategy, Commander. I wanted to personally commend you. I feel it is the least I can do.”

“Thank you. I will send any special requests via encrypted telegrams.” Madiha said.

“I will keep someone on hand to handle communications, round-the-clock. Mark my words, we will retake the reins of this war, Major. We will overcome this together.”

“Thank you again, Warden.” Madiha gripped the handset and worked through a sudden shot of anxiety. “If I can make one request now: I would like to talk to you personally in Solstice. Not simply about things present, but also those past. I hope that can be arranged.”

There was a moment of silence on the line, but Kansal replied nonetheless. She sounded a little deflated. “I owe you that much, Madiha. It has been a long time, I admit, since I have thought of that fateful day where I put the gun into your little hands and told you to shoot. Perhaps that is an indictment on my character. I was so willing to forget.”

“I remember most of those days fairly well now, Shacha. On that day, I shot because I wanted to protect you. I was small; I didn’t understand what I was doing completely. But I did it of my own volition, not because you made me do it. All of this was never something that I was coerced or tricked into doing.” Madiha said. “I’ve never understood your own feelings on the situation. I do not blame you. I just wish to speak to you about it.”

Parinita craned her head to one side, puzzled over the sudden turn in the conversation.

“We will speak, Madiha. As far as tricking and coercing – I would not be so quick to absolve me of my guilt. We will speak, so that you may fully remember, and then decide.”

“Yes. Until then, we should be keeping our communication sparse.” Madiha said.

“Indeed. Once again, thank you for your service, Madiha– Major.” Kansal hung up.

Madiha set down the handset. She rubbed her forehead, feeling a bit of a headache.

“What was that about?” Parinita asked. “Did something happen between you two?”

Madiha smiled. “She was one of the people who raised me into this sort of life.”

Parinita’s eyes drew wide. She wiped a few tufts of hair from the side of her face.

“Madiha, is Daksha Kansal your mother? Is this one of those secret child things?”

Madiha burst out laughing. “You’ve internalized one too many film plots, I see.”

Central District, East Sector, Kabuli Road

“Platoon 3, Panzerabteilung B of the 15th Panzer Regiment, reporting no contacts.”

On the radio, a woman’s voice. “How far have you advanced?”

“Five kilometers. We are moving at pace with our infantry.” replied the Sergeant.

“How is the terrain? Have the roads been damaged? Do you see any earthworks?”

“There are no defenses in sight yet and the roads are mostly navigable.”

There was silence as the voice on the radio conferred with her own superiors.

“Advance one kilometer but keep your eyes peeled for ambushes. There are networks of tunnels around the area and the Ayvartans will use anything as cover. Ruined buildings, the sewers, the roofs and second stories of intact buildings, street corners, rubble mounds.”

“Understood. Will report back after any contact is made, or in one kilometer.”

That was all the Feldwebel in command of 3-B could offer in response. Though he wanted to ask how he was supposed to move forward if those were the conditions, he knew it would be impertinent. Surrounded by roofs, by ruins; did this mean nowhere was safe?

Panzerabteilung B had a storied combat history.

Founded four years ago, they fought in Cissea through the entire conflict against the terrorist rebel forces in support of the newly declared democratic government, and participated in quelling risings in Bakor at the request of the legitimate government of the islands. Equipped at first with M2 Rangers, the untested panzerkadetts of the 15th Panzer Regiment proved themselves in battle again and again, crushing motor and armor forces, scattering entrenched infantry, overrunning fortifications in brutal assaults. Platoon 3 had proudly participated in these engagements, showing no fear before the enemy.

Now their arsenal was upgraded – with their faster, stronger M4 Sentinels there was no force treading the ground on Aer that could stand up to them in a direct confrontation.

Therein lay the problem. This was not a field where two columns met in the open.

Organized as a platoon made up of five M4 tanks from the 13th Panzergrenadier regiment, and backed up by thirty Panzergrenadier support infantry on foot, they had been tasked to recon in force. On their maps this district was simply named “Kabuli” for “Kabuli road,” the main thoroughfare connected to Penance in the south. But this mission was not a conquest, not yet. Command was not authorizing a full-scale attack despite the orders to move. This was only a limited mission to probe potential routes for such an attack.

Though only a Platoon, the men on this mission counted themselves first and foremost as among the storied Panzer B battalion. They were proud and hardened.

And yet, they felt pause.

Panzer A had only two days ago failed to penetrate Penance fast enough to stop an orderly enemy retreat. They had lost two platoons of Panzers and a company of men.

That was Panzer A, and Panzer A’s Platoons.

But they were just a Platoon too in the end.

They had a good sight line going for a stretch of 800 meters, but then the road curved around a hilly plaza and out of their immediate sight. To each side of the column there were a paltry few tight alleyways between squat, brown brick service and small shop buildings, through which no tank could penetrate at least. There was a perpendicular intersection 500 meters away. Everything was quiet; how quickly could that change?

Men and tanks advanced together. At full speed the M4 could cross over 500 meters in a minute. But they were moving at perhaps 5 km/hour. They needed their men to protect them against ambushes, and the men needed them to provide heavy firepower. It was the best arrangement these forces could muster against such a pervasively hostile environment.

The Feldwebel looked through the periscope on the commander’s seat, watching the road ahead. He peered around himself, at the tanks behind him and the tanks in front, but his eyes settled on the road ahead, and that was where he made his first contact. He quickly pushed up his hatch and stood on his seat to rise out of the cupola. He confirmed with his personal binoculars and sounded an alert. “Contact, 700 meters ahead, communist tanks!”

His lead tanks became alerted at about the same time, and their own commanders raised their hatches and stood out of their cupolas to confirm the sighting.

Coming in from the curve in the road was a platoon of Ayvartan Goblin tanks speeding down the road. Despite their smaller size they had every kind of disadvantage – they were slower than M4s due to their weaker, obsolete engine, and their smaller guns could never penetrate an M4s frontal armor except at very close range. Common cannon-fodder.

This explained their current tactics – they would charge the M4 column as fast as possible to engage in a melee. At point-blank range they could cause some damage.

“It’s a death charge, open fire and give the commies what they came here for!” shouted the Feldwebel. He moved his tank back and off to the side of the road, allowing his subordinate vehicles forward, forming a battle line with three tanks forward, one tank in reserve, and his own sheltered behind a mound of rubble. The Panzergrenadiers took up positions on both sides of the street and kept their eyes peeled, but their heads down.

As the Goblins neared 500 meters from the column, his lead tanks opened fire with their guns, their first three shells smashing into a building and over the turret of the goblin.

Those were the probing shots.

Across the line the gunners loaded new shells and the commanders ducked inside the turrets again and helped adjust the tank’s aim. At 300 meters from the enemy, the more accurate second salvo hurled fresh shells across the road and eviscerated two of the tanks. One turret flew in pieces from a hull that turned, out of control, and crashed into a nearby building; another tank was penetrated right through its strongest armor in the forward plate, the glacis, and flew into the engine, causing the tank to explode in a brilliant fireball.

This did not deter the remaining three tanks, speeding to the 100 meter danger zone.

“They’re not shooting, they’re going to ram!” Shouted a subordinate tank commander.

Gunners in the lead tanks scrambled to reload, but there was no time to shoot.

The Goblins collided their tracks and glacis plates with the M4 tanks and pulverized themselves on the armor, their tracks and drivetrains flying in pieces in every direction as they smashed against the much larger and sturdier vehicles. The Goblins struggled and ground themselves against the enemy until their treads gave out completely and their engines died out. The M4 tanks were pushed back from their orderly battle line and left scarred with hollow cavities in the armor, collapsed front hatches and broken track guards.

The Feldwebel watched from afar and sighed inwardly with some relief. None of their foolish enemies discharged their weapons. At point-blank range the 45mm gun on the Goblins was more dangerous. He thought that had been the point of the death charge.

“Inspect those tanks.” The Feldwebel shouted, addressing the infantrymen.

The Panzers disentangled themselves and retreated from the wrecked Goblins.

One M4 tank had its track damaged enough that it had to move quite tenderly on this limp, and found it particularly difficult to extricate itself from the battle line. It was rotated out to the back of the formation, and the reserve tank, untouched by the violence, took the lead in its plae. With about thirty meters of safe distance from the crashed Goblins, the Feldwebel ushered the Panzergrenadiers forward. Carefully the men climbed the tanks and opened the top hatches, apprehensive, ready to be thrown back by a potential trap.

Nothing happened. They climbed inside. They saw no one. They cleared each tank.

“Feldwebel, the Goblins are empty! They just had their drive levers jammed forward!”

“Just a trick then.” the Feldwebel said. “Lead tanks, push those out of the way.”

From their cupolas the commanders of the three lead tanks nodded to acknowledge. They dove back into their respective tanks, and drove forward. The Feldwebel started to descend into his own tank when he suddenly heard shouting that pulled his attention front.

“Contact!” shouted a Panzergrenadier, “Armor on the intersection, 480 meters!”

The Feldwebel peered into his binoculars and saw two tanks emerging from the corners at the intersection, one from each side of the road, driving out of cover with their side plates facing the column and their turrets turned on them as well. These were not Goblin tanks. They were much larger, built on long green hulls with sloped side and front plates, widely spaced tracks, and a turret mounted very close to the glacis.

They were roughly the size of an M4, but the gun was bigger.

“Medium tanks! Take aim and fire on their exposed sides!” the Feldwebel called out.

His new enemy was moments quicker.

Both of the unidentified medium tanks opened fire on the M4s. They were mounting rather powerful guns – the shells hurtled toward the column and cut the distance in a blink and exploded with force. An M4’s turret and track received the first beating. One shell pounded the ground near the track and exploded, launching the drive wheel into the air and scattering track links about. Nearly penetrating, the second shell smashed into the turret and left an enormous dent that deformed the mantlet and upset the gun’s position.

“Our gun is unseated!” shouted the commander of the stricken tank. “We can’t shoot!”

The Feldwebel shouted for the tank to move off the line, but without its track this order was impossible to fulfill. Hatches opened and the tank crew evacuated and ran back from the fighting. His two remaining forward tanks retaliated, shooting over and between the goblin wrecks. Their shells crashed into the ground as the enemy tanks retreated around the street corners. The Feldwebel cursed. These tanks were faster than he had anticipated.

Now there was another wreck in his way that had to be moved – the damaged M4.

“We cannot engage them like this!” The Feldwebel shouted to his troops. “Retreat!”

His own tank was the first to reverse away from the Goblin wrecks, and the Panzergrenadiers ran up both sides of the road to get away. Because of its track damage, the slowed-down M4 that was cycled to the rear was abandoned as well, its interior purposely damaged by a bundle of grenades to prevent any useful capture.

Its crew dashed off with the Panzergrenadiers.

Finally the two remaining line tanks started to reverse and pulled away, building up speed, firing their guns at the intersection. While the drivers pulled them back, the gunners feverishly loaded and launched shells targeting the street and road behind them to preempt pursuit. Like a boxer’s jabs, they launched shells to keep the enemy at bay. With the crews working themselves raw, the tanks sustained a rate of fire of 15 shells a minute – every eight or ten seconds a gun fired, and dust and gravel went up in the air along the intersection.

In the midst of this gunfire both the Ayvartan tanks peered across their corners again and shot their guns down the street in a circumspect fashion. Enemy shells traveled over the Panzergrenadiers and smashed the corner wall on a nearby building, and hurtled between the tanks to hit the road behind the column. The M4s kept running and kept shooting, hitting the corner buildings, knocking down a streetlight. One shell exploded directly in front of an enemy tank, kicking up pavement onto its green glacis.

Again the enemy tanks retreated around the intersection, this time without a victim.

They did not peek out to shoot again; the continuous fire from the M4s pinned them.

Tense minutes of reversed fighting later the Feldwebel peered out of his cupola.

They were almost a kilometer from the intersection and the enemy had stopped firing on them. The Panzergrenadiers started to slow down, and the retreating tanks paused to reorient themselves, turning their tracks so that they could drive away from the intersection rather than retreating in their reverse gear. For safety’s sake, one tank kept its turret pointing toward the intersection, but the other faced its gun forward.

Perhaps 10 to 15 shells remained in each tank.

They had gone through much of their ammunition.

With the heat of battle having passed, the Feldwebel picked up his radio and reported.

“This is Feldwebel Crom to command. We made contact with an Ayvartan force. Events transpired too quickly for an in-combat report. We disabled five Ayvartan Goblin tanks that were seemingly rigged to spring a trap on us, and then two medium tanks of an unidentified model attacked us, and disabled two of our tanks. We incurred no casualties – both crews evacuated safely. We have lost visual contact with the enemy and retreated 500 meters. Requesting assistance and resupply. We are low on ammunition and fuel.”

There was a brief silence and then the radio operator answered. “Hold your position and await reinforcement. Platoon 2 of Panzerabteilung C is on its way.” She said.

“Acknowledged.” He said. “We will hold here. I do not believe the enemy will advance. We can establish a defensive line and await Panzer C. I’ll keep you notified.”

“Once you have linked up with C, carefully pursue contact,” added the voice on the radio. She sounded tense. “Command would like to capture one of these tanks.”

“Indeed. Hopefully they have not vanished into the stones.”

He hung up the radio again.

Feldwebel Crom climbed out of his tank and issued orders.

He concealed his tank as best as he could behind a mostly collapsed wall in a nearby building. On each street he positioned his line tanks as close to the buildings as they could be, facing upstreet toward the intersection. He ordered the crews of the destroyed tanks to vacate, and a squad of Panzergrenadiers left with them. His two remaining squadrons of men divided themselves along both sides of the road, covering the tanks.

He felt confident in this position. Here the road was fairly narrow, and there were no alleyways around him through which a tank could fit. Most of the buildings around the column were either intact or so utterly ruined he could see through them to the building behind them and sometimes out to the next block or street over.

Any attacks would be obvious to him.

Withdrawing a cigarette from a pouch under his jacket, Feldwebel Crom climbed out of the tank and jumped down onto the street. He lit his cigarette and leaned against one of the partially collapsed exterior walls of his ruin. Panzer C would take maybe twenty or thirty minutes to reach them. He had time to take some of the edge off his nerves.

Curse those Ayvartan cowards – had they fought him in the Plaza or around that Cathedral he would have shown them how tanks really fight. Not by peeking around corners furtively firing their guns, but by charging at top speed, circling each other like bloodthirsty sharks, firing their guns on the run and taking burning bites from each other.

That was how Panzer B had fought in Cissea and in Bakor!

Not this tiptoeing game of tag!

He went through his first cigarette viciously, sucking out the smoke in desperation, tossed it on the ground, leaving it burning on the debris-strewn floor. He took another from his pocket it, lit it and smoked it too. He blew a cloud gray as the paint on his M4.

Raising his eyes across the street, he saw a hint of movement behind a window.

“Landsers!” He shouted to some of his men across the street. “Inspect that building–”

Glass shattered, concrete flew.

Across the street, at deadly close range, the facade of the quiet old building toppled over onto the road, and over the debris an enormous Ayvartan tank suddenly appeared, forcing its way through the building and onto the street. Machine gun fire from the ball-mount on its glacis raked the street and forced Feldwebel Crom behind a wall for cover.

His Panzergrenadiers clung to cover and kept out of the beast’s sight; the heavy tank turned its turret on the M4s instead. With one shot it claimed its first hunting prize, punching through the engine block and setting ablaze another of the battalion’s prized M4s.

Compared to the other tanks it was a monster – Feldwebel Crom had never seen a tank that big in any arsenal. It shared the same wide-spaced tracks and forward-mounted turret as the previous tanks but it was larger, thicker, taller. A behemoth; it stepped onto the street, the heavy machine guns on its glacis and turret cracking incessantly as it reloaded its gun.

Panzerwurfmines flew from the hands of scared infantrymen, crashing ineffectually around the enemy tank. Most of the grenades had not had their canvas fins fully deployed; those that managed to strike left ugly dents in the turret and glacis of the Ayvartan tank but scored no penetrations. Turning around its turret around over its exposed engine block, the remaining M4 desperately attacked, unleashing an armor-piercing shell at close range. The Feldwebel’s tank joined in, firing its own gun from the ruin, both within 30 meters.

Both shells deflected off the turret, launching skyward harmlessly.

In the next instant the monster’s barrel flashed. It punched a hole the size of a human head into the turret of the remaining line M4. Smoke erupted from the end of its gun barrel; its top hatches blew open from the pressure. Soon its engine began to smoke and burn.

Around the street the Panzergrenadiers began to retreat through the alleyways.

Feldwebel Crom scrambled into his tank, and screamed to his driver.

“Start it and run! Run!” He shouted, shutting his top hatch, his heart racing.

Before his driver had even manipulated the levers, the enemy tank turned its gun.

In the instant the Feldwebel’s tank backed out into the street, it was shot through.

An armor piercing shell crashed through the engine block and punched into the driving compartment. Under the Feldwebel it exploded, wreaking havoc in the cramped quarters. Concussions, burns, shrapnel; all manner of trauma visited the tanker whose armor was defeated by a tank shell. Once invincible, the M4 now became a cast steel tomb.

Surveying the carnage, pitted with the scars of failed penetrations, the Ayvartan Ogre tank brushed aside the wrecked hulls and drove up the street, to meet the Hobgoblins further ahead and thank them for their collaboration in another successful day’s hunting.

Central District – En Route To “Agni’s House”

In preparation for battle in Bada Aso many supplies had been moved underground, and various locations around the city had been earmarked as dumps where periodically supplies from the tunnels would be moved up. This was all part of a pre-war defensive plan that Madiha heavily modified to her own purposes. From the dumps, supplies could be circulated to units fighting in the locality. Soon after the bombings and the fighting, however, there was a massive disarray and many supply locations had become unusable.

Every action plan drafted before the war was meaningless. For most Ox officers and units, their limited training leaned heavily on rehearsal and execution of these plans.

From the 22nd forward, nobody’s logistic maps made any kind of sense anymore.

There was a fight to conduct and not enough good staff to bring order back to the system. They needed to focus on the fighting primarily, so intelligence and command arms took priority, and the logistics staff in turn received precious little radio operation and organizational support. They had to do what they could on their own terms instead.

This state of affairs did not deter the laborers from their necessary tasks. At night and in the early morning the drivers dutifully took their orders from the paltry few teams of administration staff in the various line corps. They mounted their trucks and set off this way and that, exploring the city as if it was a new domain with each passing day of the war.

Drivers systematically visited each of the potential caches on their maps, and found themselves often confronted with empty lots or utter ruins, with caches moved at the last minute for fear of an enemy penetration, with tunnels that had been sealed off. When the delivery and the storage elements finally met, they had to sort out conflicting orders.

At the end of the journey, the front line tended to receive mismatched quantities of ammunition, replacement guns, and food and sundries. One unit would receive more rifles than clips, another a preponderance of shells for tanks or guns they had few of on the lines, a third misappropriated engineer tech that they would then have to put to use somehow.

It was a barely working mess and communication was pitiful.

Still, everyone tried their damnedest and made do with what they could get their hands on, and they fought on. Thanks to the Major’s planning and Nocht’s carelessness, sketchy logistics proved less of an issue than they otherwise would’ve been. They lost any kind of offensive initiative in this state, but offensive initiative was never in the books. Even with haphazard supplies they could still sit behind sandbag walls and plot ambushes.

But perhaps it was good that their original plans had gone up in smoke.

After all, the rehearsed plan called for a bloody counterattack to retake the city after exhausting the enemy. That was one part of the plan that Madiha Nakar had struck out of the books immediately. What was on-hand simply could not support such an action.

On the 30th, the situation stabilized somewhat.

With the destruction of the 1st and 2nd Line Corps came the obsolescence of their part of the ragged supply network. Drivers wiped almost half of Bada Aso from their maps. The 3rd and 4th Line Corps were well rested and over the course of the battle’s 9 days, had managed to save up a good hoard of equipment with which to fight their future battle. This lessened the need for logistical back and forth. Calm settled over the supply network.

Despite this, nobody could get a hold of anybody else in the cache sites on the radio.

So the Commander and her Secretary had to quickly learn the tactics of supply drivers.

Major Madiha Nakar and Chief Warrant Officer Parinita Maharani drove their staff car north from the forward operating base, having been told vaguely that Sergeant Agni and some of her crew had left for one of the northern dumps to begin their special task. But characteristically of Bada Aso logistics, nobody quite knew which dump she had ended up going to. Madiha drove from one dump to the next, passing by a junkyard, a Msanii building, and an unfinished underground railroad station. Parinita marked them off the map.

“Next is the Adjar Sporting Society soccer field. We can keep going and drive by.”

Feeling a little agitated, Madiha turned the wheel sharply and followed her secretary’s directions to the north and east, bypassing a little commercial strip with some cooperative shops and the sports club’s equipment workshop. They drove by the field and saw nothing and nobody save the twisted remains of 37mm anti-air guns in the middle of the pitch.

Agni would have had a crew working on a tank or two. This was obviously not it.

“I knew it was bad, but seeing it myself, it’s a wonder how we get any supplies to the front at all.” Madiha said. She drove aimlessly around the field while Parinita plotted their next stop. “How has this happened? Why can’t we keep better track of active caches?”

“I’m not sure. I thought I had people working on this, but it’s just not been a priority. We’ve been going from crisis to crisis.” Parinita said, eyes scanning over the map.

“I guess there’s no point in making it a priority this late.” Madiha lamented. It was in technical areas like this that their lack of coordination seemed most pressing and dire.

“Hey, there’s a cache in a movie theater east of here. We should go.” Parinita said.

Madiha looked critically at Parinita. “So are we going there because you think Agni will be there; or because you want to go see a movie theater?” She asked.

“There’s a lot of space you can fit a tank into.” Parinita said.

She smirked and shrugged.

The Major peered over the map.

The theater was close by, the car had plenty of fuel and there were not very many other choices to consider, so Madiha ultimately complied. She broke off from the block they had been circling around and headed north and east, driving at a leisurely pace down a small strip of commercial buildings. At the end of the street, they found their little theater.

A humble rectangular brick building, it had partially collapsed, its right side showing some damage likely caused by a small bomb. Several holes along the facade suggested rockets had stricken the building. In front of it the street was covered in glass and concrete shards, and further up the street a trio of anti-air guns had been turned to slag. A few movie posters survived the attack and were still prominently displayed on the building’s front.

“Agni’s obviously not here.” Madiha said dryly, parking the car in front of the theater.

Parinita clumsily dismounted the car and ran up to the theater with stars in her eyes, her boots cracking the shards of glass pooled across the street. In a fervor she withdrew her sidearm and blasted open the display cases. She picked the posters off display racks, rolled them up, and brought a big pile of them back to the car, dumping them in the back seat.

Madiha stared quizzically, craning her neck to follow Parinita as she circled the car.

When Parinita got back on the passenger’s seat, Madiha was still staring at her.

“They’re collectible! When the movie leaves circulation these posters leave with it! This is a piece of film history I’ve got in the back seat!” Parinita emphatically said.

Madiha fished one of the posters off the pile and unrolled it.

Much of the poster was taken up by a lake that looked thick and gooey, with a hand sticking out of the muck; at the corner of the poster, near the written credits on the bottom, an Ayvartan man and woman screamed and cowered in fear of The Living Mud.

She threw it back and picked up a different one.

There was a salacious image of two muscular, oily men in very tight athletic trunks and nothing else, both standing eye to eye in the middle of a field, one with a ball in his hands and the other reaching out to him, and the film was titled Hard In The Pitch.

“It doesn’t matter what the film is about! It’s about owning the poster.” Parinita said.

“Are you going to hang this one up?” Madiha asked about the sports film poster.

“No! But I’ll keep it in a sleeve. I’ll preserve it, and I’ll know I have it!” Parinita said.

“Pity. It could go well with certain aesthetics.” Madiha said. She gently returned it.

After this detour they took up the map and headed west.

Madiha reasoned that Agni would probably elect to go to a factory, and they narrowed it down to only the factories nearby. On their map no factory was actually marked for what it produced – after driving by a small rubber processing plant and cobbler’s co-op inexplicably labeled a “factory” they finally came upon what was then ‘Agni’s House’.

From a distance Madiha saw activity in a small automobile factory and mechanical garage, once a fledging part of the local union of automobile workers. Most promising was the sight of two KVW half-tracks parked outside, and a few guards watching the road.

Just off a side road, the garage occupied a concrete lot between two old tenements. One of the tenements had received a heavy bomb through it, and had collapsed. Rubble seemed to form a ring around the space. While the main factory had been gutted of good equipment prior to the bombing, and subsequently lost its roof and one wall, a side-garage with a tin roof and a sliding door stood intact. Equipped with a heavy vehicle lift and a crane, as well as boxes of good quality metal tools, it made a perfect spot for Agni’s work.

Madiha and Parinita found her sitting atop the heavy lift upon which the body of a Goblin teletank was set. Its turret hung pitifully from the chain hoist crane nearby.

“Hujambo!” Madiha and Parinita said at once. They stood off to the side of the tank.

“Hujambo.” Agni replied. She shifted herself around to greet them. She was her usual self, inexpressive, her long hair collected into a sloppy tail, various grease stains on her person. Her jacket and shirt lay on the floor, and she had on a dirty tanktop while working. On her lap was a metal toolbox. Some of its contents seemed to have ended up on the ground. There were wire cutters, a wrench, a crowbar, and various nuts and bolts.

“Keeping busy?” Madiha smiled. “I hope you’re not pushing yourself too hard.”

“It was only a flesh wound; and these are not bags under my eyes. It’s just my eyes.”

Agni pulled on the skin around her eyes as if to demonstrate. Madiha thought they still looked like bags, and she knew Agni barely seemed to sleep. She did not belabor the point.

“It wasn’t a flesh wound at all, you suffered muscle damage.” Parinita said. She didn’t really know Agni, but that did not dull her concern. “You should not be up there at all.”

“I am keeping off my legs, as you can see.” Agni raised her dangling legs over the edge of the tank. There were bandages around one leg and a thick, spongy patch over the knife wound in her thigh. “I’ll be fine. I’m the only one who can perform these upgrades.”

“You could delegate to your subordinates. They’re just standing around.” Parinita said.

“I must do this myself to insure quality. It is vitally important. You’re distracting me.”

Parinita crossed her arms. “Well, fine then, I guess. Keep at it until you break.”

Madiha cleared her throat loudly. “So, Agni, what are you working on there?”

Agni pointed down at the tank, and spoke quickly, seeming almost excited. “I found a solution to our teletank range problems. These tank radios,” she thrust her finger sharply toward the interior of the Goblin, “are an older model than those found in Hobgoblins. We can use the better parts on the Hobgoblins to save us some time modifying the teletanks.”

“That makes sense. I honestly don’t know what goes into building a Hobgoblin – Inspector General Kimani just brought them in without much explanation.” Madiha replied.

“I don’t have a technical sheet on them, but from what I’ve heard from logistics and admin, their gun is similar to our 76mm field guns, but the power plant is different and the engine is a new model. We’ve had trouble repairing them due to this.” Parinita said.

“This is true; they use non-standard parts. High quality, but not in our stocks.” Agni replied. “However, that is working in our favor now. I had my cadre this morning gut the radios from some of the Line Corps Hobgoblins and modified the power plant and radio control receiver on the teletank with the parts. In addition, if I can gut the radio control equipment from the Control tank and install it on a Hobgoblin command-type tank, it will not only triple the operational range of the teletanks, it will offer greater protection.”

Madiha felt a sense of relief. Agni had a solution – they were still on track. Now all they had to do is buy time. “Anything you don’t use, have it blown up in the northern district.” She told Agni. “We don’t want Hobgoblin parts falling into enemy hands.”

“Yes ma’am.” Agni said. “I believe we will ready to proceed by the 35th of the Gloom.”

“That’s good. We just have to keep Nocht at bay for another week.” Madiha said. There was no sarcasm or bitterness in her voice. In fact the 30th had brought good news all around.

“We reestablished contact with Solstice today,” Parinita said, tapping on her clipboard, “and they’re willing to send a few trains, some even today, but the next ones on the 34th can carry anything you need to complete the job. So if you have a list of needed–”

“I’m committed to doing this job with what I have on-hand.” Agni replied.

Parinita hugged her clipboard closer, looking a little annoyed to be cut off by her.

“May I continue my work, Commander?” Agni asked, holding up her toolbox.

Madiha bowed her head in acknowledgment. “You may continue. Thank you for your efforts, Agni. I will insure you and your crew are adequately rewarded for your dedication.”

“Unnecessary.” Agni said.

With that parting word, she pushed her toolbox into the goblin, and then leaned down into the hull. Her legs dangled outside at first, and she almost seemed to be swimming in the vehicle. She shifted forward, swinging her hips, and her legs started to rise over her upper body. Parts and tools rattled inside the hull – Agni fell carelessly over inside.

Parinita sighed audibly.

Madiha shook her head.

They saw a wrench rise from the turret hole.

“I’m fine.” Agni said. “It only hurts a little bit and I’m sure I can get out eventually.”

“She gets a bit tetchy when she’s absorbed in her work.” Madiha whispered to Parinita.

Before leaving the garage, Madiha called over a few of Agni’s subordinates and gave them a few key instructions that might not have constituted common sense to them: keep Agni fed, keep the radio on and someone monitoring it, and finally, extricate Agni from the hull every so often. Everyone easily agreed tot these basic requests.

While Madiha rounded up and organized the engineers, Parinita checked the supply crates stacked inside the remains of the main building, but none of them were labeled nor opened, so she gave up on categorizing them or marking this dump in any particular way.

They returned to the car, and Parinita threw away her clipboard.

She crossed her arms and had a long, frustrated sigh.

“No markings of any sort, and I didn’t feel like cracking open a dozen crates to see if we’ve really got two tons of food and six tons of ammo in here or what.”

“Don’t obsess over it too much. Soon it won’t really matter.” Madiha said.

She figured they were now part of a long and storied line of staff continuously ignoring this problem. She would have to make a point to take logistics much more seriously.

“Let’s get back, we need to oversee the evacuations tonight, and get ready in case the enemy attacks.” Madiha said. She patted Parinita in the shoulder, smiling.

“Yes ma’am.” Parinita replied. She saluted cheerfully.

Since it was no longer necessary for her to navigate, Parinita took the time to inspect her treasures. She reached behind her back and unfurled a poster. There was a picture of a sheaf of wheat, with a suitcase and a hat, leaving behind a farm. It looked like the poster for an educational film about collective agriculture. Parinita threw it over her shoulder.

“If you’re not going to hang up that one, I might be interested.” Madiha said, chuckling.

Northeast District – Train Station, Night

Despite advances in technology, war had not yet defeated darkness. Conflict waned as the forces lost daylight. Both sides transported supplies primarily in the dark hours, when opposing planes and artillery would find it difficult to strike and enemy infantry would be reluctant to move. Aside from a few disparate night bombings by Anka biplanes flying in from the lower Tambwe, neither side had launched a significant night attack.

Madiha counted on this, but still felt a little tension in the dark.

Standing astride the tracks at the northern railyard, Parinita loyally at her side, the Commander waited for the arrival of an armored train. On the road outside the rail station grounds, hundreds of trucks and cars and even a few tanks came and went, ferrying thousands of wounded, sick and exhausted soldiers and a few civilians, all of whom would be leaving that night for Solstice. On one train or on another, all of them had to go.

There would be three armored trains coming and going a few hours apart. Even with their capacity, however, it might not be enough. She had almost 12,000 whom she wanted to transport and she had hoped to be able to evacuate a few tons of supplies as well. But she needed only to look over her shoulder and out onto the street and road, and see all the men and women under the faint light of electric torches and Hobgoblin tank headlights, to disabuse herself of that notion. There would be no room here except for these people and the bare minimum of goods to keep them alive on their journey away from the conflict.

Crates of spare ammo were not priority. It was time that these souls left Hell.

“When we get back, put together a team to oversee the destruction of extraneous ammunition. Hellfire might solve that for us but we can’t take any chances.” Madiha said.

“Understood.” Parinita replied. “I’ll pull some people from our intelligence team.”

“Good idea. Intel will be less necessary now that we’re drawing down from the battle.”

“Not to mention our intelligence, aside from radio capture, has been limited anyway.”

Madiha felt tired. She made an effort to stand, and she felt herself nod off once or twice in the gloom and silence. It seemed like ages since she had a full night’s sleep. Her eyes lingered on the empty tracks, on the odd shadows of cranes, on the distant, empty warehouses. Cold winds blew through station and yard. Parinita moved a little closer after a strong gust, clinging to her. Madiha felt the warmth of her body; a fond sensation.

“It’s an uncharacteristically cold night for Adjar.” Parinita said, nearly arm to arm with Madiha. It was not a situation that Madiha would rush to change. She smiled at her.

Then in the distance, Madiha thought she saw a glint of light.

She brushed it off as a trick of her eyes in the dark – but she was not the only one who saw it. One of her guards rushed forward and pointed a BKV anti-tank rifle out toward the warehouses. She peered through her scope and seemed to find something in the gloom.

“Commander, something’s approaching! I see a headlight through the scope!” She said.

Madiha and Parinita stepped back, giving Corporal Kajari some room. She was a recent addition to the 3rd Motor Rifles, but had already proven herself well, and had been handpicked by Lt. Batuzi to serve as part of the rail guard for the night. Her superior, Sergeant Chadgura, stepped onto the platform to support her subordinate and stared down her own BKV scope to confirm the sighting. She nodded her head at Madiha, silently corroborating the Corporal’s discovery. Both kept their guns trained forward.

“Ma’am, you two should take cover behind the platform just in case.” Chadgura said.

“It doesn’t look like a tank,” Kajari said, “I think it’s got wheels. We may be able to–”

“Hold your fire unless I say so.” Madiha said.

She stepped off the platform, taking Parinita with her by the hand.

They crouched behind the brick, and heard footsteps as Chadgura and Kajari, and other guards around them, took positions behind what cover they could find.

Madiha breathed deep and concentrated. Her eyes felt hot, but they did not hurt.

She felt a sharp feeling in her skull and her vision swam, rising as though her eyes were sliding up. Vision left her body; her vantage, what her eyes saw, soared far over the rail platform, as though she peered down at the world from a surveillance plane. Gently the scope glided over the rails, out to the warehouses, and found the approaching vehicle – an enclosed, 8-wheeled scout car, four on each side. It was a rather familiar model.

Shaking her head grounded her perception firmly within her eyesockets. There was a residual chill, a shuddering and disassociation, a lack of control over her body, but she regained enough presence to try to climb the platform again. Parinita reached out to her.

“Madiha, wait,” she said, grabbing her by the shoulder. She drew a handkerchief from her jacket and wiped around Madiha’s ear, and then showed her the discharge. It was blood.

“That’s inconvenient.” Madiha said, sighing. She thought she had mastered this by now.

Parinita approached and pressed her hands on Madiha’s cheeks, locking eyes with her. Madiha felt the slight burning in her eyes cool off, completely, instantly. Parinita let her go, and nodded toward the platform. “Just be more careful from now on, alright?”

Madiha nodded, and climbed again on the platform.

She looked through a pair of binoculars in the dark at the approaching vehicle and waved her hand at her guards to tell them off. “It’s one of ours! Everybody stand down!” She shouted quickly, the little binoculars serving as justification for her knowledge, despite having as poor a range and capability in the dark as the scopes on the BKVs.

Without question, Corporal Kajari and Sergeant Chadgura put down their BKVs, and waved down the machine gunners and riflemen and women that had gathered around the platform. They stood down, and Madiha ordered them back to their positions near the road.

Slowly the vehicle approached.

Once it came close enough they could see it was an Adze scout car with a circular aerial – the command type vehicle. It drove toward the platform and parked just off the track with its side-door facing the platofrm. From the vehicle a tall woman stepped out, with short, curly hair slicked back, a gold-and-red uniform, and a striking dark countenance. She approached the platform, climb it in one jump, and took Madiha in her arms.

“Thank the Ancestors you’re safe,” said Inspector General Chinedu Kimani. “Madiha.”

Being in those arms took her back to her childhood.

She remembered that feeling now – she could be fond of it. She could feel nostalgic over it. Kimani’s arms, embracing her, protecting her, picking her up when she was small, all of this she remembered. She had been there so much for her in the past.

“Chinedu,” Madiha said simply. She smiled. “I’m glad to see you. Are you alright?”

“I am fine.” Her voice sounded more emphatic than before. She pulled herself away from Madiha, and saluted her respectfully. “I will be evacuating via the sea with you, Major, so I had to leave the Kalu behing. Things are going about as well as they could in that area.”

“I’ll make sure you can keep in contact.” Madiha said. “Thank you, Chinedu.”

“Do not thank me; I would not have given the enemy any pause without our comrades.”

“No, I mean,” Madiha made her eyes glow again, “thank you for everything, Chinedu.”

Kimani smiled a little in response.

This was an incredibly rare sight. For a moment the two of them were framed in light as they came to a silent understanding – the searchlights on the approaching trains shone on them, and the noise drowned out any more of their words. Bristling with anti-tank guns and anti-tair guns and pulling a heavy 203 mm artillery gun car in the back, the first of the massive armored trains stopped just behind them, and opened its doors.

“I think I have to supervise this, Inspector General.” Madiha said. She smiled.

“I leave the situation in your capable hands, Commander.” Kimani said. “If you require my advice or aid, I will be by your side. I hope to be more available from now on.”

“I appreciate your expertise.” Madiha said. She saluted her. Kimani saluted back.

Parinita stepped onto the platform, and ushered forward the first group of evacuees. From the trains, KVW agents helped accommodate the wounded and sick in the cars. Accommodations were not luxurious, but slowly, under the stars and the light of electric torches many of the survivors of the first battles of Bada Aso boarded the train, ready to be ferried out of Hell and into the future, where, hopefully, they could heal and grow.

Madiha saw the glow of life in all of them, and she felt it strongly in herself.

She did not regret the past.