25-AG-30 South District, Matumaini Upper Street

Luftlotte bombs had hit the blocks connected by Matumaini Street particularly hard.

There were many collapses. Holes were blown into the streets and the asphalt. Many buildings and roads sank, fully or partially, into the tunnels under the city or into the sewer.

One particularly large collapse was the postal building on Matumaini’s 5th block.

Once a large, bustling place, it had been blasted so that it resembled nothing so much as a hell maw, a burrow, a slit into the earth surrounded by mounds of rubble that cast the hole between them into darkness. Matumaini Post Office had largely sunk into its own basement, where supplies were kept. Thankfully the building had been promptly declared unsafe and fully evacuated by Engineering before the bombings began in earnest.

Nobody was supposed to be anywhere near there; but a curious mission had been given to a private from the 2nd Line Corps that seemed to suggest otherwise.

“Uh, hello? I’m Private Hanabi. I was told to check if someone was stuck here?”

He raised a hand to shield his eyes and stared into the dark pit formed by the ruins.

Someone responded to him quite quickly in a calm, droning tone of voice.

“Hujambo. I’m Corporal Chadgura. I am trapped. But I am fine with this situation.”

Pvt. Hanabi leaned carefully into the rubble and looked down the collapsed floor.

“Oh. Well. You should probably come out of there. Did something happen to you?”

Corporal Chadgura looked up at the Private from the interior of the ruin, and produced for him a small booklet. She raised it up so that he could see it. She flipped the pages quite deliberately so that he could appreciate the contents of every one.

It was a stamp book, and each page had multiple copies of a different stamp.

Most of the stamps were pictures of places in Ayvarta, monuments like the People’s Peak in Solstice, the Kucha Mountains and the great oil fields on the Horn of Ayvarta. Some pages had pictures of revolutionary martyrs, local cultural heroes, and other colorful folklore. Every region had its own circulation of commemorative stamps.

Once she was sure Pvt. Hanabi had fully come to appreciate her discovery, Cpl. Chadgura closed the book and put it in her bag with a triumphant flourish.

“So,” Pvt. Hanabi looked confused for a moment, “You collect stamps?”

“Yes.” Cpl. Chadgura replied. Her voice had lost a lot of its natural character. When she spoke it was fairly monotonous. Deep inside though, she felt rather pleased with her acquisition, even if her face and voice did not show it. She looked over the stamps in the book again, and imagined with great pleasure cutting them from the pages, and sticking them on her book. “I travel regularly. So I collect stamps from the regional post offices.”

“Oh. Do you keep them in a book?” Pvt. Hanabi asked. “I know people do that.”

“Yes. I have a stamp book. I left it at the HQ. A staff member is taking care of it.”

“I see. You wouldn’t want it to get damaged in the fighting.”

“Yes. I used to have an older book, and it was damaged. I had to transplant the surviving stamps to a new book. I learned my lesson then. I was very distraught when that book was burnt. But I am fine now.” She remembered her speech training as she spoke with Pvt. Hanabi. Make frequent use of ‘I’ statements to more easily construct sentences and convey information; remember to declare your emotions so others can tell how you are doing; remind others of your condition so they can better help you.

She remembered her emotive words, like ‘distraught’, ‘fine’, ‘sad’, ‘happy’.

Most people couldn’t tell just from her face and voice.

Pvt. Hanabi stared at her, but he was not unfriendly toward her when he spoke.

“Do you need help getting out of there?”

“While I am personally fine, I do require assistance to escape this hole.” She replied.

“Ok. I’ll go get some rope. There’s an engineer just across the street.”

“I will wait here patiently.”

“Uh, good. Don’t panic or anything, I’ll be right back.”

“I am physically incapable of panic. Thank you for your help.” Cpl. Chadgura said.

Among the agents in her training group, she had been one of the worst speakers both before and after her conditioning was over, necessitating she take additional speech training and therapy. She thought, however, that she did quite well with Pvt. Hanabi.

Once the engineer returned with a rope and they pulled her out of the hole, she casually walked down to the intersection to rejoin the 2nd Line Corps, hoping her new stamps would survive the battle. If not she supposed that Bada Aso had many more post offices. She felt little trepidation about it, but she did feel a desire for her stamps to survive.

It had been hours since the last sandbag had gone down over the intersection.

Preparing the defense had come down to the wire, but everyone had made it.

Now all the 2nd Line Corps’ troops could do was to wait.

For many it was a casual wait despite the fact that death might loom on the horizon. They ate, they ambled around the line, they talked with each other, and they cleaned and checked their kit in anticipation. There were hundreds in the intersection and most were being a little noisy. Soldiers cracked open their meager rations of palm wine and banana gin, drinking the liquor down while telling stories or singing songs. Less enthusiastic folk sat around their guns or mortars and tried to get to sleep. There was also at least one game of Ayvartan chess, Chatarunga, being played nearby with a sandbag holding the board.

Private Gulab Kajari watched the game intently.

Back in her village they liked Shatranj, which was quite similar to Chatarunga. It differed from Lubonin chess, Latrones, in that the peasants did not get a double move to begin with and you could not hide the king behind the chariots. One thing Gulab did like better about Latrones over the other variants of the game was that the best piece was a Queen and not a Counselor. She always found that rather heartening. Her grandfather had taught her to play. Before he passed he was the best player in their region.

During the old old war he had played a lot of chess in the different places he fought.

Almost on reflex she found herself muttering a little prayer.

Gulab herself had played many games, of Chatarunga, Chatranj, Latrones and even the Nochtish Schach. As a kid she had nurtured some ambition for this game of warring royals, and she had even played people in villages outside her own. She played enough that it was a little frustrating to watch some of the clumsy moves being made by the soldiers.

They were cowardly and indecisive, and when they committed it was to foolish moves.

Both of them stared at the board for long minutes and then almost always made mistakes. Soon she could not bear to watch anymore. It grated on her nerves to see it.

She turned on her back on the sight, facing an empty building.

Waiting was starting to get on her nerves too.

Almost reflexively she pulled her hair free, gathered it again and began to braid it into a tail, just for something to do. Her hair was long and a little wavy, a bit messy, rich dark chestnut in color, darker than the brown tone of her skin. Whenever she could spare the time she meticulously tied her hair up in a simple braid. Since being redeployed from the wilderness outposts in the Kalu Hilltops she had precious little idle time to spend on hair.

Toying with her hair was simple and relaxing – it helped affirm a lot of who she was. Whenever she braided her own hair it brought back memories of home. It was hard not to think about it. There was a lot about her that had been bound up in those simple twists of her gathered hair, that was bound up in the length of her hair, in the care that she took with it; a lot that made her different. Back in her village, hair braiding was a kind of boundary that she crossed. She was brazen, and usually asked girls to braid her hair.

They would have thought it strange, but they would have done it, giggling and laughing and saying silly things about her. They would go to one of the girls’ homes while their family was out, and they would braid her hair and paint her face and smile.

They would say she was pretty and had a cute-looking face, and comment on how slender and soft she was compared to her brothers. Gulab would enjoy the teasing thoroughly. It was all compliments to her, unbeknownst to the girls making them.

Those were good times.

She was on the last twist, her fingers right right at the lower end of her hair, when she heard noise and commotion. She finished her braid with a little elastic band she had gotten out of a toolbox months ago. From the middle of the vehicle road, Lt. Kone shouted and raised his radio handset up over his head. “We’ve received orders to take up positions! As of right now, carry yourselves as though an attack is imminent!”

As one, the soldiers heeded him.

Food and drink were thrown away, and the Chatarunga pieces went back in their case.

There was smoke over Matumaini and 3rd, rising from several blocks away.

The defenders made it to their positions, and waited, knowing they were soon to be drawn into battle. Gulab went over in her mind what she thought of the situation. She had not played chess all those years without thinking about life in moves – she had gone through effort to try to understand the situation today. She had asked people, looked at maps.

Building collapses made it impossible to see the actions of the enemy from this distance, but they were certainly on the move. Sounds of gunfire intensified, at first distant, but moving closer and heightening in volume. To attack the line, the Nochtish forces would have curve around the heavy collapses on Matumaini 1st and connect to the adjacent Goa street east of Matumaini and then return through the western connection to Matumaini 2nd.

Now finally around the rubble, they could turn around back into Matumaini and assault north along the road and directly within the lane of fire held by the 2nd Line Corps’ 42nd Ox Rifles Regiment, tasked with occupying Matumaini 3rd. This was the only route that made sense at the moment, since there was no direct connection to Penance in the west.

It seemed the enemy was ready to do just that.

Already remnants of the 1st Line Corps had begun retreating.

Over the next half hour Gulab saw injured and scared men and women coming in from the south, from the smoke and the din of gunfire. Medical units of the 2nd Line Corps were soon busy with the remnants of the 1st Line Corps, who largely had to be transported away behind the lines. Matumaini 3rd would be the main battlefield in moments.

Matumaini 3rd’s defenders established themselves along the intersection separating the blocks on Matumaini 2nd with those on Matumaini 3rd. It was a very open and broad four-way intersection. The streets were wide and several building lots straddling the road had been pounded into crushed dust, opening up even more terrain for the defenders.

Gulab had never quite seen a road layout like this one.

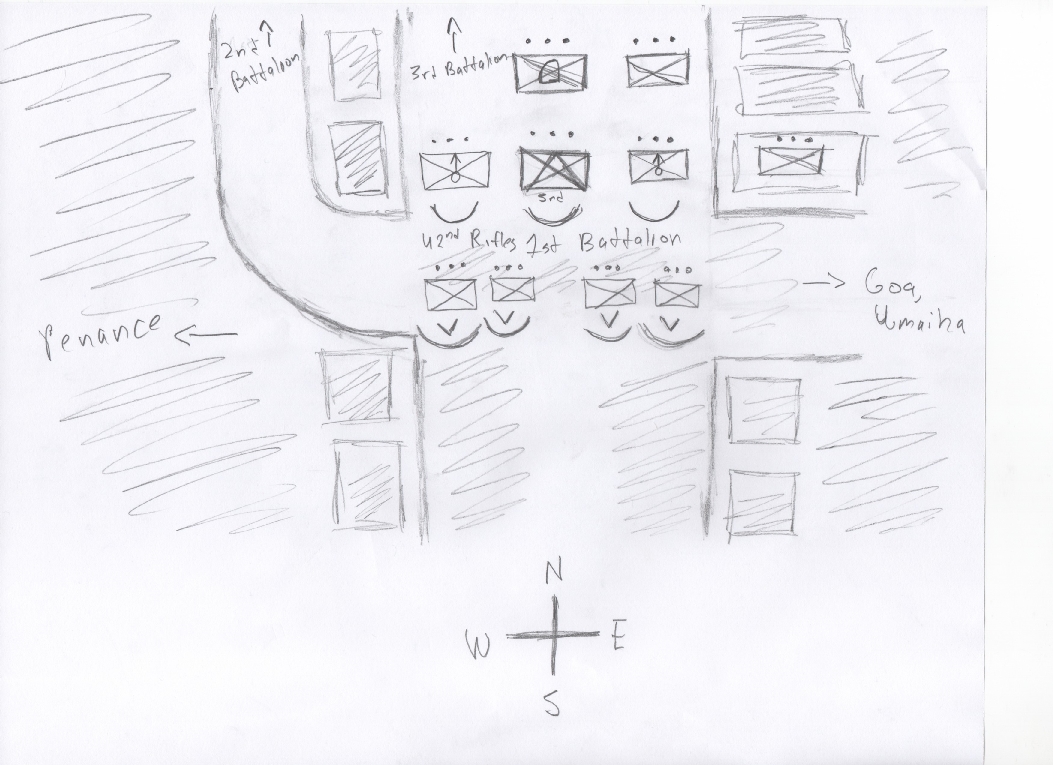

Matumaini ran along the northern and southern ends of the intersection, with a connection west to Goa, and a diagonal connecting road to the next district curling into the intersection from the northeast and bypassing Penance road and the old Cathedral block entirely. The defense of the intersection was tiered across these areas.

Each of the three battalions had its place in the defense of this area of more or less a kilometer all around. The 1st Battalion was responsible for the edge and center of the intersection, while the diagonal road was 2nd Battalion’s to hold. The extreme end of the intersection along Matumaini itself, as well as Matumaini and 4th block, to the rear of the 1st Battalion area, was 3rd Battalion’s responsibility. Gulab herself was part of the 4th Ox Rifle Division’s, 42nd Rifles’ Regiment’s 1st Battalion, B Company, 3rd Platoon.

Order of battle was confusing at times.

She thought of herself mostly as “3rd Platoon,” but the defense of the intersection made her think in larger terms than that. There were a lot of people present. When she joined the army she barely trained with twenty or thirty people. Perhaps had she been around longer, and in a better time, these masses of humanity would seem normal.

Sandbag walls had been erected along the southern end of the road. The 42nd Rifle Regiment’s 1st Battalion did not have enough sandbags to wall off the entire intersection, it was simply too large. Instead, several half-moon firing positions had been made, with a machine gun, anti-tank gun or mortar providing a base of fire for a platoon of rifle troops.

There were four large positions along the south with heavy machine guns and a rifle platoon stacking around or near each. In the center of the intersection there were three more positions, one for an anti-tank platoon and two for mortar platoons, along with supporting defenses centered on a mostly intact residential building on the northeast, straddling the intersection toward Goa and Umaiha, and mostly harboring light machine gunners and rifle troops. Far to the back was their supply platoon, and a reserve rifle platoon occupying the connection to the 3rd Battalion area in case of retreat. This was their full disposition.

Gulab and the 3rd Platoon was in the center.

She was part of a platoon stationed around a grouping of three 45mm anti-tank guns.

Her thoughts finally arrived at her own disposition. In this way she ran through the situation in her head, waiting with bated breath for the enemy. For nearly an hour everyone was quite static, but surprisingly, a latecomer arrived at the 1st Battalion area.

“I apologize for being late, Lieutenant. I shall take charge of the platoon now.”

Over her shoulder, Gulab listened in on Lt. Kone and his new guest. He was in a mortar pit adjacent to her post. She wondered why he wasn’t chewing out this woman who was light-only-knows how late to the defense, and worse, late to command her own troops! And she wondered even more what kind of pathetic character would be late to something of this magnitude, late to her command responsibilities. She almost had half a mind to say something to this fool later on – but then she caught a good glimpse of the woman.

Gulab was stunned to silence.

Lt. Kone deferred to the newcomer because she was a KVW agent; but Gulab found herself staring at the woman just because she looked so gallant in uniform.

Soon the woman approached the 3rd Platoon’s position. Gulab was still transfixed.

“Hujambo, I am Corporal Charvi Chadgura. I will be temporarily in command.”

Cpl. Chadgura shared perhaps the dullest hujambo Gulab had ever heard.

She spoke and carried herself completely without expression. Her eyes were just a little bit narrowed, and her lips remained in a neutral position when she quieted. She wore neither a smile nor a frown. Her cheeks were relaxed, and there was not a wrinkle along her brow. She had a striking appearance in spite her lack of expression, with a rich and dark complexion, and slightly curly, strangely pale hair to a length below chin level. It was a collection of traits that Gulab had never seen in the mountains, the Kalu, or Bada Aso.

It was hard for Gulab to accept this picturesque person as the owner of that dull and droning voice, as someone who had been late to assemble her own platoon – as a less-than-perfect officer. Especially for KVW, heralded as terrifying, perfect soldiers.

Everyone in the platoon was quiet for a moment.

It seemed that there was no one among them used to dealing with the KVW, or perhaps, specifically with someone like the corporal, who had a sort of scatter-brained air from the moment she appeared. Gulab could not tell what Corporal Chadgura was thinking, and the Corporal was very quiet and still. She tried in vain to find somewhere to sit, but then remained standing. There were no other officers in their platoon. It was a young unit.

Cpl. Chadgura rubbed the side of her own arm perhaps as a form of fidgeting.

Her face continued to betray nothing of what she was thinking. She was a complete cipher. Finally, after long silence, she found a place to sit down on the sandbag wall.

Once she seated she patted her hand on her lap as if beckoning a child.

“Does anyone want to join my command cadre?” She asked in her droning voice.

There was no response at first. It seemed the answer was a hesitant ‘no.’

Without thinking Gulab thrust her hand up, feeling as if she had a duty to do so.

Now the platoon stared at her instead. Cpl. Chadgura clapped her hands once.

“Thank you. One person will be enough. What is your name and rank?”

“Private Gulab Kajari, ma’am!” Gulab said. She tried to seem enthusiastic.

Chadgura rubbed her chin as if she had forgotten something. She cast a long glance around the platoon, then snapped her fingers. It was the most expressive gesture she had made so far. “Private Kajari, please share with everyone one thing that you enjoy doing.”

Gulab paused for a moment.

“I like Chess.” She finally said in a hushed voice.

“I enjoy collecting stamps. Now we know each other on a deeper level.”

Chadgura’s expression did not change at all, there was not even the slightest twitch.

Nobody in the platoon could peel themselves away from this scene.

Even Gulab found it puzzling.