This chapter contains scenes of violence and death.

25th of the Aster’s Gloom, 2030 D.C.E.

The World was always burning. Whenever steel cut the air and ripped souls from their bodies, the Flame surged in the heart of the World. There was a time when everybody could see the fire. There were Things That Ruled this world, and they thought they knew best the fickle appetites of the flame. But there were also the People, and in a time forgotten they made war on the Things That Ruled and fed them all to the Flame.

In that instant, it was brighter than it was ever meant to be.

Never again would it grow so bright.

That was the divine time, a long forgotten minute in the lifespan of the universe.

The divine time is long past. Steel flies, souls scatter, but the Flame dwindles.

In the heart of the old continent however, the People traded scraps of that lost history, and they thought, like the Things That Ruled once did, that they knew the Flame best.

“There is a way yet, to gather the flame. Our divinity is not all gone.”

They erected a throne, and there they sat the one who would lead them.

Madiha sat in the throne. She stared down at her subjects with a grim and stately face. Monoliths rose around her, blocking out the sun. They were each as tall as mountains. She was hot, and sweating, and she felt the banging of drums right in the center of her breast, and it was thrilling. There were fire dancers in heated rhythm at the edge of her vision. For a time she was alone in the center of things. Then her subjects finally appeared in flesh, wearing nothing but masks, and they approached her, and they knelt, and they made offerings to her, as though she were a God. She grinned viciously toward them.

“Remember your virtues, old Warlord,” said a person with a fish mask.

“Cunning,” said a person in a bird mask offering hawk’s eye’s earrings.

“Command,” intoned a person in a cat mask offering a lion’s mane.

“Fearlessness,” lulled a person wearing a hyena’s snout offering a necklace of teeth.

Then entered a creature with a man’s mask, in iron, a pitiless face banged into shape over coals. Madiha could not understand its body – was it a Thing That Ruled?

It offered her only a rusty, bloody spear and it hissed: “Ferocity.“

Madiha saw the flames in their eyes vanish, and all of them sink into her own, and the fires trailed from her face forming her own half-mask, and she screamed, in a horrible, all-consuming pain, down the center of her skull, across her spine, to where the tail once was, and down the arms and legs that ended in claws. They were always the Things That Ruled?

25-AG-30: Ox HQ, Madiha’s House

It was close to midnight when Madiha awoke with a start, scattering a stack of maps and documents that had accumulated on her desk over the course of the day’s fighting.

All of the lights had been snuffed out as a passive defense against retaliatory bombing; even her oil lamp was out. She woke in the dark. Slivers of silver moonlight struggled to penetrate the dark drizzling clouds outside. There was a figure softly sleeping on a nearby table whom she assumed to be Parinita, hugging a pack radio they had set up on a chair – this box was the comrade most in touch with what was happening south of the HQ.

“Parinita?” Madiha called out, her lips trembling.

She struggled to move, frozen, as though there was something that would reach out and seize her at any moment if she was not careful. Her lungs worked themselves raw, her breathing choppy. Her eyes stung with tears and cold, dripping sweat.

It was a struggle to keep herself from falling fetal on the ground.

Her secretary woke slowly, peeking her head up from over the radio.

She flicked a switch on its side by accident and a series of tiny globes on the radio pack lit brihglty up and cast Parinita’s face in an eerie green glow. Her secretary stretched out her arms, yawned and rubbed the waking tears from her blurry eyes.

“Good morning Madiha.” She said drowsily. “Are you alright?”

“It’s not morning.” Madiha replied. Her voice was choked and desperate.

“Something wrong?” Parinita asked. “Did you have a nightmare?”

Parinita’s kind words came like a slap to the back of the head.

Madiha felt childish now – yes, she had experienced a nightmare.

She was awake enough now to understand it was not real. But it had seemed so urgent, so horrible, just a few seconds ago. It had made her tongue feel stuck against the floor of her mouth. It had driven the power to move from her. She had felt terror of a sort that nothing yet had caused her. She did not understand the images – the dire figures approached and spoke but she did not remember their contours or the content of their words.

These distorted things invoked a primal horror in her that still took her breath.

Communicating all of that felt foolish now. She turned away her gaze.

“I’m fine. It’s fine.” She said.

“If you say so.” Parinita replied, a little sadly.

“I’ll go back to sleep. Sorry for waking you.”

“It is fine.” Parinita said. “I pray that the Spirits might help still your thoughts.”

Madiha rested her head against her desk, and curled her arms around her face.

Her eyes remained wide open for the rest of the night.

She tried to recall those terrible images, but they faded more with each passing moment. That toxic thing that resided in her breast was growing closer and stronger, and yet her strange power grew no more accessible than before. Perhaps they were not linked at all.

Perhaps one was the gift and the other just the curse, never intertwined.

27th of the Aster’s Gloom, 2030 D.C.E.

Adjar Dominance – City of Bada Aso, South District

6th Day of the Battle of Bada Aso

Matumaini was a ghost street, and the southern district was starkly quiet.

Fighting that had been terribly fierce the past days had all but burnt itself out.

No snapping of distant rifles, no rumbling of artillery, no belabored scratching of tracks and treads. Where once columns a thousand rifles in strength challenged one another, now only the corpses, rubble, spent casings, and the lingering dust and smoke remained. It was a calm in the eye of the storm, and there was little shelter left to endure the weather.

Much of the southern district had been ruined, by artillery, by the tank attacks; and by the engineering battalion of the 3rd KVW Motor Rifles Division, diligently at work since the end of the 22nd’s air raids. Many of the ruins had been planned by them.

Those that weren’t were carefully considered and made part of the rest of the plan. They had funneled Nocht right where they wanted them to go, and many of their comrades paid dearly as the unknowingly caged dogs charged into prepared defenses.

Then, things became complex. By necessity, their plans became fluid.

A small column of vehicles moved under the cover of rain and stormclouds.

Two half-tracks and one of the Hobgoblin medium tanks departed Madiha’s house and made it quickly down Sese Street and into Matumaini Street. They passed vacant positions, destroyed guns, the hulks of vehicles friendly and enemy alike. The Hobgoblin pushed them quickly aside, opening a path for the wheeled vehicles. They drove past bodies and they drove past ruins. Some ruins were marked on the tactical maps.

Some were fresh, and would have to be inspected if time allowed.

One half-track carried two squadrons of KVW soldiers, and another a squadron of soldiers along with Madiha and a cadre – Parinita, Agni, and a few staff and engineers.

They stopped on the edge of Matumaini and 3rd. Madiha climbed the ladder up to the shooting platform of the half-track. Parinita stood hip to hip with her on the platform, holding up a parasol to cover her commander from the rain. The Major produced a pair of binoculars and inspected the intersection from afar. She traded with her secretary, holding the umbrella for a moment so she could see. Parinita whistled, impressed by the damage.

“I think the enemy will be content enough to leave this place alone.”

Parinita seemed calm and certain, and it was easy for her to be. Despite being in the middle of a war, right now it felt eerily like the aftermath, like the last bullet had flown.

But Hellfire had not yet even started. They were still setting up.

Madiha was still burdened with disquiet.

Her mind still spoke out of turn, demanding things from her. Her hands shook. Large bags had formed under her eyes. And the sound of the bombs still rang in her ears.

Outside it was quiet, yes, but the war still maintained its rhythm in a vulnerable heart.

“Do you think any of the pipeline has been compromised?” She asked Parinita.

Parinita adjusted her reading glasses. “I think we’d be well aware if it was!”

Madiha looked down her binoculars again atop the half-track.

From her vantage she had a good look at the intersection on Matumaini and 3rd block.

Constant artillery barrages had caused the road to collapse into the sewer, a massive sinkhole forming between the roads and rendering them largely unusable without further construction. To hold each individual link in the intersection would be pointless – this was an area the enemy would certainly ignore now. That had not been the plan. Madiha had wanted Nocht to commit strength and then have a path north. She wanted them to keep bodies moving into the grinder. Now she would have balance yielding to Nocht while also maintaining her troop’s ability to defend and retreat in good order in order to bleed Nocht.

“Hellfire will have to recline into a small hiatus it seems. It appears to me that our counterattack scared Nocht too much. I was too disproportionate and ruthless.”

Beside her, Parinita shrugged amicably. “Kinda hard to pull punches on these fellows.”

“I want the engineers organized as soon as possible to carry out the inspection.”

Parinita nodded. “I still feel that you should not need to be on-hand for that.”

“I want to be involved. I’m done sitting around.” Madiha replied.

Parinita averted her gaze and sighed a little to herself.

They had talked about this before. It had been a tension and a subtext of all their conversations since the first drops of blood were spilled. But Madiha could not help but feel that this was an injustice. A thousand men and women could die in a single day because she put their formations on a map, and while they suffered she was a dozen kilometers away in relative safety. A gnawing poisonous voice in her mind had convinced her that this was not her place; that she should be out there; she should be suffering with them.

She was a coward not to dive toward death like them.

“You’re not a fireteam leader.” Parinita said sharply. “I wish you’d understand that.”

“It will be fine, Parinita. It’s just a surveying mission with the engineers. We will be planning routes, diving into old empty tunnels and demolishing buildings. I’m not leading an assault on Nocht’s HQ. I just want to do something other than sit in my office.”

Madiha smiled. It was difficult – more difficult than anything she had done that day.

But her keen secretary could always see through her. She was unimpressed, but she did not protest any further. Resigned, Parinita simply replied, “If you say so, Madiha.”

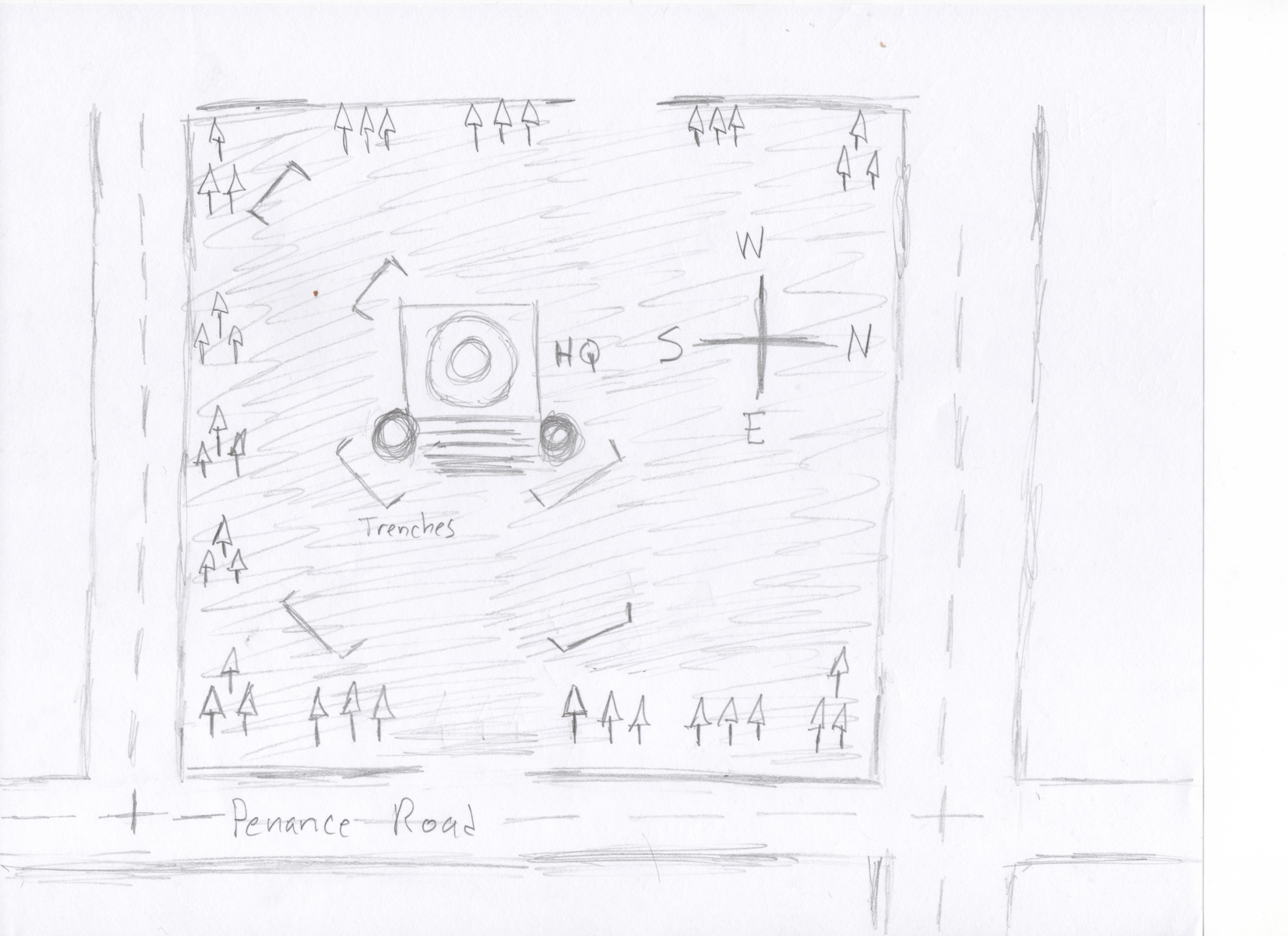

27-AG-30, Bada Aso SW, Penance Road

There was no storm yet, merely a continuous drizzling that pattered against windows, over tents and across the tarps over vehicles. Clouds gathered thick over the broad green park, turning the grass wet and muddy underfoot. A light wind rustled the line of trees around the edge of the park, standing sentinel around the expansive monument within.

The Cathedral of Our Lady of Penance, for which the main road had been named, looked all the more grim under a dark sky. Grim gray stone steps between two massive spires led up to an open maw of a doorway shut off by double steel doors. Inside, the nave was particularly spacious, almost forty meters wide inside, and easily two stories tall by itself. Its scale attested to the hopes and dreams of its engineers, and the crowds they expected to gather there during the abortive conversion of the Empire to Messianism.

Such a project, it was believed, would inspire a new golden age for the church.

A new world, full of minds to turn to the service of the Messiah.

Certainly the building, towering over the smashed ruins outside of the park’s limits, seemed an imperious presence. In the middle of the park the Cathedral seemed as old and storied as the earth. To the observer it almost appeared that the soil around the Cathedral’s flat, gray stone base actually rose to embrace the foundation, and fell ever so slightly away from it. As though the ground elevated the building a meter or two into its own little hill.

In truth the Cathedral was an irreverent child when compared to the ruins around it.

Bada Aso was a sea of stone resting half on a hill, but conspicuously flatter and taller than its surroundings, an attempt by civilization to conquer a chaotic earth millennia old. With the times it had warped and it had grown, it had fed and gorged and it jut out in every direction, toward the sea, toward the Kalu. It was one of Ayvarta’s largest, oldest cities.

It had been built first by the indigenous Umma of the region, as a place of monoliths, a shelter straddling the sea, for the gathering of fish, and of the game from the vast, hilly Kalu. Then it became a throne of stone and brick set into place by the Ayvartan Empire, a symbol of the strength of Solstice, the invincible city in the heart of the red sands.

Many of the people who would eventually bring down the throne in Solstice grew up in its surrogate of Bada Aso, thriving in the place meant to control them. Tradition, Empire and Revolution lived and died in it. To this drama, the Messianic church, its teachings and its monuments, were entirely fresh faces. Indeed, communism was now longer lived than the Golden Age of Messianism in Ayvarta. Penance could not challenge this earth.

Once the Revolution overturned the Ayvartan Empire, Bada Aso quite briefly became a place of anti-communist fervor and then, remarkably, a symbol of civilized socialism, of the working order and kindness offered by the concrete and steel bosom of SDS-controlled cities. There was guaranteed housing and food, clinics and state shops and canteens in seeemingly every block, large tenements to keep everyone from the autumn rains, wage stipends for those unwilling or unable to work, and work aplenty for those that wanted it.

Bada Aso had been built and built over according to different time periods, ideologies, and functions. There were streets leading nowhere, byways blocked off by stark brick cul de sacs to keep traffic from spilling out to more than one road, buildings of varying size and style all organized into long uneven blocks that made up the many districts. It was an organic city, a thing that had grown in the same inexplicable way the humans within it grew. It was too tight in places and too open in others. With time, it might have grown even ganglier, more haphazard, its streets the expanding veins of a massive history.

Now the city was on its final journey.

Again the forces of reaction teemed within it.

A fifth of the city had practically been given to the 1st Vorkampfer, an army from abroad coming to reintroduce empire to Bada Aso. Bombing had ruined much of the city. Controlled demolition had rendered many places inaccessible. Four-fifths of the population had been evacuated. Those who remained did so to continue their socialist labor far behind the battle lines – serving food, sewing uniforms, dressing wounds, offering condolences.

Penance Cathedral served as well.

It was an eerie fortress, its true purpose mostly forgotten.

Along its corners trenches had been dug into the park soil, lined with sandbags, filled with men and women and their guns. There were snipers on the spires, and mortars perched precariously atop the dome. Atop the steps, a pair of 76mm divisional field guns had been angled to fire easily against the road approaches.

Inside the nave there were crates of ammunition, food, medicine, all watching a sermon led by a reserve anti-tank gun pointed out the doors. Benches had been pushed aside and there were beds and crates and a radio station set in their place. A Company from the 6th Ox Rifles Division was all that kept these sacred stones from turning hands now.

Penance had not seen battle like Matumaini.

Just a series of actions that sputtered and choked off under the shadow of that Cathedral.

To Ox command, this meant that a larger attack would certainly be forthcoming.

Under the rain, a truck entered the Cathedral district from the northwest, careful to circle the edge of the park, driving with the trees between it and the main thoroughfare. Once the the truck turned and approached the Cathedral from behind, the structure itself provided all the cover it needed from the road in case of a sudden attack.

Facing its lightly armored front to the back of the building, it parked; a passenger dismounted, and knocked on the back door of the cathedral. A woman peered out from the roof, watching their approach; she called in for them, and the door opened.

It was safe – everyone had confirmed everyone else was a comrade.

The truck swung around to make its contents accessible.

In the bed there were crates of medicine, food, canvas; a large section of sandbags and poles and tarps and other construction materials in the back; and atop the sandbags a group of eight soldiers in black and red uniforms, their officer laying unsteadily on her side.

Recently promoted Sergeant Charvi Chadgura had a hand on her stomach and another over her mouth. Her garrison cap lay discarded. She curled her legs.

“I’m car sick.” She droned dispassionately.

Beside her a deputy, newly-minted Corporal Gulab Kajari, stared at her quizzically, fanning the Sergeant with her cap. “How did you ride the tank and then get car sick?”

“It keeps rocking.” Sgt. Chadgura said. Her toneless voice was muffled by her gloves.

“Sergeant, we have a mission! You need to be healthy when we receive our orders!”

“I will be fine in a few minutes. Or an hour.” The Sergeant started to turn a little pale.

Gulab tried rubbing Chadgura’s stomach and fanning her faster with her cap to keep her cool. She had no idea what to do about motion sickness – back in the Kucha they would have just told her to endure it or to get sick in some place nobody had to see.

Once the truck stopped, everyone decided to give Chadgura a moment of stillness.

While she laid down, Gulab and the others picked up crates from the end of the bed and carried them into the Cathedral. There they would be stockpiled for the battle ahead.

Each crate was over a meter wide and tall, and stuffed full of individual ration boxes, or ammunition in belts, clips and magazines. Unloading trucks was a chore nobody was happy to perform, but the KVW troops took to it silently and diligently. They settled quickly into a teamwork system– quickly passing crates to one another in a line to get them out the truck bed and into the nave easily. As the officer on-hand, Gulab stood at the end of the line, and boisterously laid the crates down in the back room of the nave.

She was unperturbed by the weight and stacked the boxes with theatrical flourish.

“Woo hoo! We can carry another crate, can’t we comrades? Certainly one more crate! Ha ha!” Gulab said as more and more crates visibly neared along the line of hands.

This enthusiasm did not go unnoticed.

Gulab did such a fantastic job, and she was so happy and very eager to do it, that once Chadgura recovered and went to contact the commanding officer at the Cathedral, Gulab and the KVW squadron were volunteered to unload several other trucks that day.

Towed 122mm howitzers were brought one by one, and she and her troops unhitched them and arranged them at the tree-line north of the Cathedral for the crews soon to be arriving; three Goblin tanks and a truck full of spare parts and portable machine tools arrived, and the Corporal saw to it that these supplies were set apart, and that the fuel was well stored to keep dry and safe; a half-track with large antennae across its roof arrived at the Cathedral, dropped off a long-range radio set, picked up fuel and food from the stacks, and drove off again, to hide on the edges of the district; but overall most of it was trucks with common supplies. Crate after dark brown crate was unloaded and stacked.

Most of it was ammo and sandbags, but several were rations too.

Slowly, over the course of the day, the Cathedral troops built up various disparate types of materiel and personnel. Within a dozen hours they had a small but serviceable local artillery arm, a tiny armored squadron, and, under the odd direction of Corporal Kajari and Sergeant Chadgura, a minuscule but experienced assault tactics formation for special maneuvers and consulting. Under the irreverent young stones of the Cathedral they would fight to give the old stones of Bada Aso a few more days before Hellfire.

Private Adesh Gurunath rocked back and forth in a dreamless sleep atop one of the benches along the left wall of the nave in Penance Cathedral. He had arrived a few hours earlier on a truck similar to Corporal Kajari’s, carrying supplies and disparate reinforcement personnel. From the moment he appeared, the officers on site had been sympathetic and told him to rest. But he felt fine; as good as he could feel after the tragedy that befell him.

However, since there were only two 76mm guns, and he was part of a gunnery crew, he had nothing to do except relieve a current crew, taking turns. So he waited, and he slept. Atop the cold wood he twisted and turned for hours, until he heard a sharp whistling.

Adesh got up too fast; he felt a slight jolt of pain up his shoulder and along his breast.

Eshe loomed over him so close that they almost banged foreheads.

“Oh, I’m sorry!” Eshe said, rubbing Adesh’s shoulder. “I didn’t think, I was a brute-”

“It is fine,” Adesh said, a little exasperated, “It is fine, Eshe. Are we moving?”

“Almost our turn at the gun. Corporal wanted us to get some fresh ammunition for it.”

Adesh nodded. He understood the Corporal wanted him and Nnenia to carry the shells.

Eshe’s arm had been hurt, and it was still in a sling; though no bones had been broken, shrapnel had injured his muscles, and movement would be limited for a time. Despite this, he did not slack in his commitment. His uniform was crisp and neat as always, his hair combed and waxed, his shoes shined. He wore his cap at all times. Professional, collected, a model soldier boy like in the posters. Still at the front even though injured; devoted.

Just not exactly able to lift heavy crates at the moment.

In that regard, Adesh was fairly lucky. A few days rest in a clinic had done him a lot of good. Surviving the dive bombing attack on the the 22nd of the Gloom left him with burns along his chest, over his shoulder and down his back, and a long, ugly burn across his neck that made it feel a bit stiff, but nothing too bad in the final reckoning.

His burns were healing well and did not impede him overmuch, so he had volunteered to return to the front when he could. He looked overall less in disarray than before, despite the bandages up to his neck under his jacket and shirt. His long, messy ponytail had been cut at the hospital. Once he had the presence of mind to do so, he asked that his hair be styled, and it was cut on the sides and back to a neck-length bob. His bangs had been trimmed neatly. After an eye examination a pair of glasses had been issued to him.

They had a noticeable weight on his nose.

After he was released, both Nnenia and Eshe, teaming up for practically the first time, made faces at him and told him he looked cute, like a little desk secretary. He didn’t know whether to take it as a joke, or if they were being serious about his appearance.

“Where is Nnenia? Asleep too?” Eshe asked. He cast quick glances about the nave.

“A few benches down; don’t whistle at her.” Adesh warned.

Nnenia was liable to punch him.

With a hand from Eshe, Adesh stood from the bench and jumped over the backrest. They approached a bench a little ways down the wall; this time Eshe shook the occupant. Nnenia growled and shook and moaned for a few minutes more. Minutes were given, and then Eshe shook her again. She nearly bit his good hand, then woke like a grumpy housecat, staring his way with eyes half-closed and her teeth grit. She sat up, legs up against her chest.

“Good morning.” She mumbled, tying her hair into a short tail.

“It’s nearly evening by now.” Eshe said gently. “And our turn at the gun.”

Nnenia sharply corrected herself. “Good morning, Adesh.”

Eshe exhaled sadly; Adesh raised his hand in awkward greeting.

Nnenia stood up and climbed over the bench by herself, and stood behind Eshe as though awaiting a chance to bite him in the shoulder. Together they crossed the nave into the backroom, where fresh supplies were coming in via truck. Adesh was surprised to find black-uniformed personnel carrying the crates and stacking them around. These were troops of the KVW – the uniform of the elite Uvuli was a black jacket and pants with red trim and gold buttons, and a patch with the nine-headed hydra, superimposed red on a black circle. It was eerie to see these agents carrying crates. They looked so common.

Prior to joining the military he barely heard of the KVW, and knew nothing concrete. Since arriving in Bada Aso Adesh had been quickly brought to speed by everyone around him on all the rumors surrounding the KVW. How they hunted traitors in the night during the scandals years ago, choking them in their own homes after finding secret radio sets transmitting to enemies; how they stared down the barrels of guns fearlessly, ignoring injury and rushing to bloody melee; how they were given special drugs and therapies so they could see in darkness, never miss a shot, and kill without compunction.

These people did not resemble those people.

“Welcome, comrades! Need anything?”

There was an energetic young woman at the fore, soft-faced and smiling at everybody. She appeared supervising the squadron as they went about their work. She had the crates stacked up in a haphazard step pyramid. Judging by her patches, she was a Corporal.

“Hujambo,” Eshe said, easily taking the lead for his squad. “Are you in charge?”

“Not really, I don’t think! I just unload! Help yourselves to whatever.” She replied.

Eshe tipped his head. “I’m Eshe Chittur. If I might have your own name?”

Nnenia and Adesh introduced themselves more quietly and awkwardly.

Across from them the lady beamed and crossed her arms happily.

“Of course, comrade! I am Corporal Kajari, an officer in Major Nakar’s own elite 3rd KVW Motor Rifles Division!” Kajari stuck out her chest, and tapped her fist once against the flat of her breast, wearing a big proud grin. “Don’t be so stiff, if you kids need anything, just know that you can come to this mountain girl for support. I take care of my comrades like a Rock Bear mama! Take anything you need from the stack. I insist that you do!”

Her tone of voice became more grandiose the more she spoke, as though she were inspiring herself to speak mid-sentence. She looked fairly short, a little shorter than Eshe, and she was slender and unassuming in figure, but the long simple braid of chestnut-brown hair, the bright orange eyes that were slightly narrowed in appearance, and the honey-colored tone of her skin, did remind one of the hardy folk of the Kucha Mountains.

But Adesh knew little specific about them.

“Thanks, but we only need 76mm shells.” Eshe said curtly. He looked put off by her tone. “You seem boisterous for an Uvuli, if I do say, ma’am. Are you the squad leader?”

Corporal Kajari grinned at him, and turned around and pointed at a KVW soldier.

“Private! Am I or am I not your officer?” She asked.

“You are, ma’am,” replied the soldier, saluting stiffly, his face a perpetual near-frown.

“How come you act nothing like them?” Eshe pressed her. He sounded a bit offended.

For a moment the Corporal looked at him. She put her hands on her hips and smirked.

“It’s a specific sort of training that makes you like that. Not all of us are like this,” Corporal Kajari half-closed her eyes and frowned, putting on a sort of sleepy expression, making fun of the stoicism emblematic of the KVW, “High Command thought such training would only dull my powerful abilities! I have acquitted myself so well, that it has been found thoroughly unnecessary, in fact even detrimental, to train me further! It is feared it might dull my considerable skill in killing people and destroying positions and such.”

Nnenia whistled. Adesh smiled. Much to Eshe’s chagrin, they took well immediately to the officer. All of Adesh’s trepidation toward the KVW vanished, and he was taken in by the friendly officer. She held the young soldiers up for a moment and started telling them a few quick stories, while the rest of her troop unloaded without her.

Eshe stood off to one side, sighing at the scene.

Kajari gathered them and told them about how she had shot a man out of a window from two-hundred meters away during the fight for Matumaini – a battle Adesh and his friends had largely sat out in a ward behind the lines, recovering wounds. She told them about riding on a tank, and saving her CO from a Nochtish assault gun. This act had her promoted to Corporal from a lowly private. It gave Adesh hope for the future.

She told them how she survived a brutal artillery strike that caved-in the entire street around them, and how she ran and ran, with the ground collapsing at her wake!

Then she jumped at the last moment, and her Corporal, now a Sergeant, grabbed her hand, pulled her up, and told her she was a real socialist hero, and that now they were even!

“I see a lot of myself in you kids,” she said, hooking her arms around Adesh and Nnenia’s shoulders and pulling them close to her, rubbing cheeks, “y’got potential, I can tell! Give your all against the imperialist scum! I’m sure you’ll make them bleed white!”

“Thank you, Corporal Kajari!” Nnenia and Adesh said at once, cheeks and ears flushed beet read, laughing jovially with the officer. They hugged tightly against her chest.

The Corporal looked positively in love with them!

And Adesh felt amazingly comfortable with her. Eshe started tapping his feet, and regrettably they had to step away from their spontaneous Rock Bear Mama and her radiating charisma. To each of the doting young ones she gave a parting gift, a ration from a crate lying at her feet – when Eshe protested that this was against regulation she ordered him, as a superior officer, to shut his mouth up and to lighten up at once.

“At least two of you are going places!” She said again, nodding her head sagely.

Eshe stared at his shoes, making little noises inside his mouth.

Outside the building another truck arrived, this one towing what looked like an anti-aircraft gun. The KVW troops started to gather around it. Blowing kisses and walking out as though on a cloud, Corporal Kajari finally left the room, like a beloved theater star.

Eshe grumbled the instant she was out of earshot. “What a relentless fibber!”

“Oh, of course you’d know more about the KVW than her.” Nnenia rolled her eyes.

“As a matter of fact, I think I do.” Eshe said. “More than you, and more than her!”

“Oh, I got the red paneer!” Adesh shouted, holding up the ration box triumphantly. In his heart he thanked Comrade Kajari for keeping him well fed. This ration was his favorite!

Nnenia and Eshe watched him as he stared reverently at the package, and laughed. This seemed to diffuse all of the tension. Together they stored the rations in their packs. Eshe took great pains to stuff his under his various other possessions, all in case of an inspection that he was sure would come. He was quite alone in that sentiment.

They found the shells in a corner of the back room.

Each box had 6 shells, each shell weighing about seven kilograms. They had handles on either side that made them easier to carry, but the weight still proved challenging to the young privates less than a half hour after waking. Carrying the crates pulled their shoulders down, and they were reduced to almost to waddling in order to bear with it.

Eshe in the lead, opening the doors for them, the group carried the ordnance across the nave, out the big doors, and to the landing atop of the steps leading to the cathedral, where the two guns had been set up between the spires. They carried the crates toward the right-most of the guns under a tarp pitched up on four poles with plastic bases.

Under the tarp Corporal Rahani and Kufu greeted them.

Corporal Rahani had been largely uninjured in the blast during the air battles of the 22nd, same for Kufu. They had minor scratches, and luckily, Rahani’s pretty face had seen none of those. Rahani looked vibrant and soft as always. Having time to prepare, this time the lucky flower in his hair was not one picked off the ground, but a big bright hibiscus. He had gotten it from the stocks of a state-run goods shop farther north. Kufu meanwhile looked, if anything, more disheveled and bored than usual, reclining against the front of the gun shield with his hands behind his head. Half his buttons were undone.

Kufu waved half-heartedly at them, and nobody waved back – Nnenia and Adesh had their hands full and Eshe was not in a friendly mood. Adesh nodded his head instead.

“We brought two crates, one HE, one AP,” Eshe said, and saluted Rahani.

“Thanks for the gifts,” Cpl. Rahani said, giggling, “you can put them down right here.”

He pointed out a small stack of crates near the tarp. A few had gotten wet in the constant drizzling, but they were all closed shut. Nnenia and Adesh deposited their boxes atop the others. There was a crowbar nearby in case they needed to crack them open.

They sat atop the crates, gently laboring to calm their breathing and loosen up their shoulders. Rahani was all smiles as everyone gathered around the field gun – the same kind of 76mm long-barreled piece had Adesh had haphazardly commanded back at the border battle on the 18th, though his memory of what he did during that time was very fuzzy.

“Now it’s our turn at the gun.” Cpl. Rahani said. “Hopefully it will be a quiet one!”

From the steps, Adesh could see out to the main Penance road about 300 meters away. A line of trees across the edge of the park interrupted the view in places, but certainly if an enemy tried driving up Penance they would be spotted. A few intact buildings stood on the street opposing the park, across Penance road from the Cathedral, but it was mostly ruins all around elsewhere and of little tactical use. To cover the most direct approaches to the cathedral, six trenches and sandbag walls had been set in line with three corners of the cathedral, organized in two ranks, one closer to the edge of the park than the other.

In each trench there were light machine gunners and riflemen waiting to fight.

Atop each of the Cathedral’s spires they had snipers with BKV-28 heavy rifles, and atop the dome on the roof there was a mortar team in a somewhat precarious position but with a commanding view, along a pair of anti-aircraft machine guns, bolted to the stone.

Everything but the northwest approach, the Cathedral’s supply line, could be directly enfiladed by the defender’s weapons. Nocht had no access to a road that directly threatened the northwest supply line, unless they broke through to Penance and passed around the Cathedral itself to get to it. And by that point, there would not be much hope left.

In a few days this holy place had become a fortress. Adesh marveled at it all.

“What’s the situation so far? I’ve only heard bits and pieces.” Eshe asked.

Corporal Rahani smiled. “Nice to know your wounds haven’t slowed you down!”

“Ah, well, I’m just always looking to know something about my surroundings.”

“Is anyone else curious?” Corporal Rahani asked. Adesh didn’t quite know what for. He always thought of Eshe was something of a busybody, but in this case his curiosity made sense, and was perhaps a healthy interest to have. For Eshe’s sake, he awkwardly raised his hand, and Nnenia followed, though both were a little less eager to talk strategy.

“I’m glad I have a crew who is eager for more than just orders.” Rahani said cheerfully.

Kufu made no gesture of any kind. He might have fallen asleep against the gun shield.

Corporal Rahani gathered the privates around a sketchy pencil map of the surroundings – the Cathedral, the park, the roads framing the park. Penance, the largest road running south to north along the eastern edge of the park, was marked as the most obvious incursion point. “On the 25th there was a ground battle in the South District with its main axes around Matumaini, Penance and Umaiha Riverside. Matumaini saw the fiercest fighting, but there was a lot of death here on Penance too. Cissean troops overwhelmed the first line, and the second was ordered to retreat up here to reinforce the Cathedral. It proved too strong a point for the Cisseans – they don’t have the kind of equipment the Nochtish troops do.”

“I take it it’s been quiet since.” Eshe said. “Otherwise we would feel more alarmed.”

“Right. It seems they enemy is not eager to press the attack after what happened on the 25th.” Corporal Rahani said. “They thought sheer momentum would carry them, and were proved wrong. Our defenses and counterattacks cost them a lot of their materiel.”

“But an attack’s got to come sooner or later, and it will hit us harder now.” Eshe added. “Because Matumaini’s in bad condition for road travel. Penance is the best way north.”

“Quite correct. And furthermore that attack will probably hit sooner rather than later,” Corporal Rahani said. “As you’ve seen, Division Command has been building us up here.”

“Too slowly if you ask me.” Eshe said. He crossed his arms over his chest and spoke with a very assertive tone, as though scolding someone. “Just smatterings of infantry and bits and pieces of equipment. What if Nocht throws everything they’ve got at this place?”

Nnenia rolled her eyes. Adesh groaned a little internally. Eshe was overstepping.

“I wouldn’t blame them too much.” Corporal Rahani replied. He pressed a finger on Eshe’s shirt with a little grin on his face. “We’re still waiting to see what the enemy’s tanks do in the Kalu. They could open a second front into the city out of the east. Committing everything to the front line in the south, especially heavy weapons, would render our strategic depth vulnerable to an eastern blow. Did you consider that eventuality, Private?”

“Um, no, I did not think about the Kalu.” Eshe admitted. He sounded embarrassed.

Corporal Rahani smiled cryptically, and put away the map.

He patted Eshe on the shoulder.

“I like your enthusiasm! I hope we can all continue to grow together.”

Due to the injuries among the crew, some roles had changed.

Adesh was the gunner still, and Kufu and Nnenia adjusted the gun’s elevation and traversed it along their vantage. Corporal Rahani was now the loader, and the commander as well. He took his place at the side of the gun, and handed Eshe his hand-held radio so that he could act as their communications crew. Eshe looked a little bashful, one of the few times Adesh had seen him avert his gaze from people. He stood behind the gun, sitting quietly on the closed crates while they waited for an enemy to engage.

Adesh felt a little bad for him.

He was hard-headed, and perhaps needed to be put in his place every once in a while, but nonetheless Adesh found Eshe’s confidence mostly endearing. It was sad to see him squirming and circumspect. He was perhaps the only person Adesh was close to who seemed to have figured himself out. Though, it could be he merely acted the part well.

28th of the Aster’s Gloom, 2030 D.C.E.

City of Bada Aso – South District, Penance Cathedral

7th Day of the Battle of Bada Aso

“I want you to think really hard before you move that pawn.”

“I’ve thought about it.”

“Look at the board again.”

“I have. I’m moving the pawn.”

It was a somewhat farcical scene, but at least it kept their minds engaged.

Their much vaunted special orders had yet to come, so with nothing important to do the KVW assault squadron at the Cathedral had spent their days performing chores and passing the time. Gulab had carried boxes; helped serve the troops a hot supper by ripping open ration boxes and heating them; she had gotten carried away and told tall tales to doting privates, each with enough truth that even Gulab began to believe that was exactly how they happened; and she had run out in the rain at night to guide trucks around the park.

So came and went the 27th; on the 28th of the Gloom, their orders had still not been fully sorted out, and so in the large and ornate bedroom once belonging to the bishop, Gulab and Chadgura traded pieces on the abstract battlefield of a Latrones board they found in the basement. While the pieces were different than Chatarunga the rules were much the same. Surrounded by the rest of the squadron, they set up the pieces and took a few turns.

Now there was a strange tension between the two officers, mostly from Gulab.

“Just so you’re aware, you’re doing all the wrong things if you want to try to win this game,” Gulab said. She was growing quite impatient. She could not believe what was transpiring on the board, and it was almost insulting to see it happening before her.

“I’ve only just moved a few pawns.” Sergeant Chadgura said quickly.

“Yes, yes, and they were terrible moves. Awful moves.”

Chadgura looked at the board. It was impossible to discern whether her expression conveyed disinterest or contemplation. She picked up the pawn she had just moved, looked back up at Gulab and overturned the piece. “I’m not changing them. Your turn.”

Gulab picked up her Queen and moved it diagonally, stamping it down on the board as though she wanted the piece to go through the wood and drill into the floor.

“CHECKMATE.” She shouted. She tapped the queen on the square over and over.

“Oh. I did not notice that.” Chadgura nonchalantly replied.

Gulab sighed. “You can’t just move pieces without looking at what the opponent can do. You know how far pieces can move! I mean, I’m just,” Gulab shook her head and held her hand up to her forehead, pushing up her bangs, “What did I even set this board up for?”

“I assumed to have fun playing a game. Now I don’t know either.” Chadgura said.

Everyone in the room seemed to avert their gazes from the bed all at once, and they left its side and stood apart as though nothing awkward had happened.

Gulab felt like a firecracker had gone off right beside her ear, and choked a little.

All this time Chadgura had amicably played along with an innocent and forward attitude while Gulab nitpicked and yelled at her. She felt as though her eyes had been pulled into the sky to witness her own self from another angle and it looked very ugly.

Her behavior was so stark and frightening. That was how she got when she played Chess with people these days; it was horrible, and she never seemed to become aware that she was doing it fast enough to stop herself. All the worst parts of her seemed to rise up in this one specific arena, whether she was watching games of Chess or playing them.

“Let’s just put the board away for now.” Gulab said, feeling uncomfortable with herself.

“I wanted to try to play. But I understand and am not unhappy with your decision.”

Gulab frowned.

She did not feel particularly absolved by the clumsy phrase “not unhappy.” She did not like thinking she was so aggressive, but there was just something about Chess. There had been so much bound in it for her, and there still seemed to be so much bound in Chess. It represented something to her that it did to nobody else. There was an incongruity in her life whenever she played Chess. A question of ability and intellect. It seemed always that her opponents got worse, and her life got no better. Chess was the arena where she once thought she could prove her value and define who she was in a way nobody could argue.

Even thinking about it sickened her. Gulab turned from the board in shame.

Chadgura folded the set closed, and they put the pieces into niches carved on the side. It was a wooden briefcase-like set-top board, portable and fully self-contained. They found it in the basement of the cathedral while searching for things they could use.

This time around they would need all the resources they could carry.

They were only a single squadron.

Gulab had received a black uniform and a promotion, and was now billed as an elite KVW assault soldier. She supposed Chadgura had something to do with that.

Around the room her squadron was arrayed before her, six other men and women under her command. They were dressed now in the muted green uniform of the Territorial Army as opposed to the black and red uniforms of elite KVW assault troops, or the red and gold of high KVW officers. She was in some ways excited to lead, but in others, quite confused.

Fighting with less than 10 souls at her side seemed like suicide. Command had a mission for them to support Penance, and its mysterious goals required this small group.

Aside from that Gulab knew nothing about it, and Chadgura knew just as little.

Nobody seemed to have any questions or concerns.

Everyone whiled away their time quietly. Gulab found the room around her now largely filled with blank faces, staring quietly into infinity. Despite the time she had spent with Chadgura, it was still difficult to understand their behavior. She understood Chadgura, to an extent. She knew the rumors that KVW troops had no emotion and knew no fear were not exactly true. They felt; they were still human behind the blank faces.

However, she still found their stone-like composure a touch disquieting.

“Is something wrong with them?” Gulab whispered to the Sergeant.

“I don’t know. I can ask.” Chadgura said.

Before Gulab could intimate that she actually did not want Chadgura to ask anybody anything, and that perhaps this entire line of thought was very ill considered and ill timed and should quickly and quietly be dropped, the Sergeant turned her head over her shoulder and singled out a man who looked a few years older than both of them, perhaps in his early thirties. He stood with his back to the wall and his hands in his pockets, and his sharp features and short brow made him appear somewhat disgruntled in comparison to Chadgura. He had cropped frizzy hair and skin the color of baked leather.

“Is something wrong, Private Akabe?” Chadgura asked. Gulab averted her gaze.

Private Akabe raised his eyes to the bed. “No, I do not believe anything is wrong officer.” He spoke in a deep, drawling voice with little inflection to his words.

Chadgura looked over at Gulab again as if to say ‘See?’ in her own odd way.

Gulab shrugged. “I just don’t understand how they endure what is happening. They just stand there staring. I would feel a little offput by all this waiting around for orders.”

“I see.” Chadgura said. She turned her head over her shoulder again, and Gulab gesticulated wildly for a brief moment in protest, but again could not stop her from passing her innocent inquiries to the KVW soldiers in the room. “How do you normally endure circumstances such as this, Private Jandi? I like to think about stamps. What do you do?”

This time she addressed a young woman on the other side of the room. Private Jandi had her hair shaved close to her head, and her skin was dark enough to seem blue in the light from the window. Her striking lips and cheekbones gave her a somewhat glamorous appearance in Gulab’s eyes, a sort of mystique compounded by the disinterested expression fixed upon the features of her face. She spoke in a high-pitched but still dull tone.

“I read a lot of books. I sometimes play cards. Right now I’m focused on the mission. We could deploy at any time.” She said. “So I feel it is irresponsible to become distracted and use the time for leisure. However, ma’am, I trust my officers to do as they wish.”

Gulab cringed again, turning beet-red. She couldn’t believe she was a higher rank than this dead-serious lady. Of course, the KVW soldiers had their own little quirks despite their legendary implacability, but to Gulab there was still something eerie about the calm with which they took in their bloody business. She wished for something to occupy her mind than the grim silence of the room and the view of the ruins out the easterly window.

Despite her Corporal’s mortified expression, Chadgura quickly brought another soldier into the unwanted Q&A, Private Dabo. He was a plump young man, with a round face and slightly widened body, and lots of curly hair. His face looked sagely and contemplative in a way, as though he always saw some truth written in the air. He reminded her of Chadgura in that he had soft features, so he felt more positive to Gulab than some of the other KVW soldiers. He had his submachine gun hugged to his chest. To him, Chadgura repeated the question – how did he endure the moments ticking away? He responded in a low voice.

“I think about music. I used to sit around the tenement record player all day.” He said.

“Ah. Is the music in your mind accurate to the record’s sound?” Chadgura asked.

“I think so. I can keep the timing, and I can hum some of the tunes.” Dabo replied.

“I see; how wonderful. Sometimes I will also sit, wondering what to do, and I ‘play back’ music I have heard before, in my mind; and I wonder if it is accurate to the sound the record player makes, or if my imagination might embellish the music.” Chadgura said.

There were a few knowing nods from people around the room.

People started whispering and gesticulating toward each other, as if carrying on the conversation around the room. Meanwhile Gulab felt utterly dumbfounded, having had hardly any access to a record player in her life. She did, however, feel less embarrassed and less awkward. She marveled for a moment at how lively the room felt now that there seemed to be a subject, however strange, for all of the soldiers to share in.

There was something about this show of humanity that put Gulab back into her good spirits. Growing calm now, and wanting to make up for her behavior from before, she flipped the chess case, split it open again, and invited Chadgura to take her pieces.

“Despite Jandi’s sage advice, I will accept.” Chadgura said, and laid down her king.

“I’m not gonna go easy on you,” Gulab grinned, “But I’ll restrain my killer instinct.”

Around noon Corporal Rahani’s crew took another turn in the defensive line. Across from then the southeast trenches were fully manned, and the rest partially. Rain fell over the park only a touch heavier. Promises of a terrible storm had yet to prove true.

Aside from recurring sounds of traffic and the sound of precipitation, the front was peaceful. Nearly asleep behind the shield of his gun, Adesh heard distant noisy wheels, tracks and engines, and wondered what was being delivered to the Cathedral this time. Another anti-aircraft gun? Additional tanks? Engineers? They had enough food and ammo.

“What do you think that one is?” He asked.

Nobody heard him – they were busy around a wooden board filled with holes, six holes in two rows, each of the holes filled with seeds. Nnenia and Kufu were playing a mancala game, where stones were taken from pits and sewn along the rows of holes.

Adesh had tried watching the game but he had never liked mancala. Every region seemed to have its own rules and the particulars were difficult and confusing. Even now he didn’t know why they picked up seeds or how they captured pits. Nnenia and Kufu themselves didn’t really seem to know, at least to Adesh’s eyes, it all looked very random.

Eshe was busy giving everyone instructions and Rahani watched, amused by the crew.

Turning from the board Adesh looked over the gun and out over the park green and the road. Unable to make sense of the game he simply watched the empty landscape, taking in the rustling of trees, the vast green, and the long, empty road–

He adjusted his glasses, and something caught his attention.

Around the corner into the Cathedral square there was something large.

It was moving into the main road, and it was not moving alone.

At first he thought his mind was tricking him. Then he realized it had become his curse to receive responsibility in the midst of tragedy, the responsibility of those precious seconds before the bullets started to rain, where he could still shout and people might still live. He remembered that dive bomber coming down upon him, and he seized up in fear for a moment, but only the merest moment. Sure enough he soon found his voice to scream.

“Contact!” Adesh shouted. “Vehicles to the east, they’re protecting riflemen!”

Nnenia and Kufu overturned the mancala board standing up so fast.

Seeds scattered across the floor from the pits.

Corporal Rahani pulled his binoculars to his eyes and bit his lip; he confirmed a movement of men and a vehicle to the southeast, coming out to the two-way intersection on Penance at the park corner. From the corner trench, rifles and machine guns opened fire on the advancing men, but their targets quickly ducked behind the cover of their escort vehicle, a large, armored half-track. Unlike Ayvartan half-tracks the vehicle’s bed had well-armored walls that were high and closed off. Its hull had a long, sloped engine compartment and a well-armored driver’s compartment with small slits, making the driver a difficult target. Machine gun and rifle fire simply bounced off the Nochtish Squire Infantry Carrier.

Once out onto the intersection, the half-track turned from the road and charged into the green from between the trees. It drove toward the cathedral at an angle to shield the men running along its left side. Atop the enemy half-track, a Norgler gunner on a traversing mount opened fire on the trench. With each furious burst of gunfire Adesh saw the dust kick up all around his comrades, and their heads ducking down in response.

Good horizontal cover from the half-track protected the gunner too well from the fire he drew back. Within moments the machine would overrun the first trench.

“Everyone at their stations! Traverse, and load HE!” Corporal Rahani ordered.

Kufu and Nnenia turned the gun eastward, and lowered the barrel elevation.

Corporal Rahani loaded the shell and punched it into the breech – it snapped shut so close to his hand Adesh thought it might take off skin, but he was unscathed.

As they prepared to fire there sounded a loud bang from their right; their adjacent gun launched its first shell downrange and its crew prepared to fire a second. This first HE shell soared over the Squire’s engine block and smashed the treeline, exploding a dozen meters away. Shrapnel and wooden debris burst out in all directions, but the machine did not even shake from the distant blast, and it left no corpses behind as it advanced.

Binoculars up, Corporal Rahani shouted, “Gun ready! First round downrange!”

Adesh pulled the firing pin, and the gun rocked, sliding back to disperse the recoil. Tongues of smoke blew from the muzzle break. Adesh’s shell crossed the distance and impacted the turf several meters shy off the half-track’s right front wheel, punching a meter-wide hole into the green. Though not a direct shot, it was nonetheless deadly.

Shrapnel from the explosion blew through the wheel and pockmarked the side of the Squire, and the pressure wave rocked the vehicle. The Norgler gunner fell right off the side of the half-track, and around him the fire from the trench resumed, and he was perforated by a half-dozen shots before he even hit the ground. While the rear track labored to keep the vehicle moving, the mangled front wheel spun uselessly. It plodded on.

A man in the trench saw an opportunity and stood to throw a grenade at the half-track, but one of the men riding inside the half-track stood too and took up the gun.

He turned the fatal instrument and loosed a dozen shots into the trench.

As the grenade left his fingers the man in the trench was punched through the chest by several shots and fell back. His throw went terribly wide, exploding harmlessly away from the trench and the vehicle both. Adesh grit his teeth watching the scene play out.

One more blast from their partner gun exploded directly behind the half-track, and shook it again, but did nothing to the track and merely rattled the new gunner for a few seconds. Shots from the snipers punched small holes into the driver’s compartment, but the machine trundled ahead regardless. Soon it would be nearly atop the trench, and its men would be able to clear it with grenades from safety, and then advance on the second line.

“Adjust angle! We’ll get them!” Corporal Rahani said. He pushed an Armor-Piercing shell into the breech and gave some mathematical instructions. Nnenia and Kufu adjusted the gun based on Rahani’s estimates. Behind them, Eshe contributed by using his good hand to open shell crates with the crowbard so Rahani could load from them.

Adesh muttered a prayer to the spirits and pulled the firing pin.

There was a roar and a powerful kick from the gun. In an instant the Armor-Piercing High-Explosive shell crossed the park and punched through the Squire’s engine block and into the crew space, detonating close to the driver’s compartment and igniting fuel.

Within seconds the advancing half-track was a husk, its engine block a black smear on the turf, its driver vaporized, and the compartment fully open from the front. Machine gun fire through the gaping hole in the front cut through the survivors in the vehicle’s bed like fish in a barrel. Though the men running alongside the vehicle were mostly untouched by the blast, they had lost their moving cover, and hunkered down behind the bed.

From the trench several comrades rose and threw grenades at the husk aiming to hit the soldiers. They had pistols and bayonets, and it seemed the skirmish was nearly decided.

“Good hit!” Corporal Rahani said. He looked through his binoculars, examining the remains of the husk, and then looked out to the road. “Load HE, and let us put the fear–”

A small plume of fire and smoke rose suddenly in front of the outer trench, tossing dirt and grass into the air. Comrades in mid-charge were flung back into the trenches they came from and many were wounded by shrapnel. There was a sudden screaming of alert across the other trenches, and the gun crews atop the Cathedral steps hesitated from shock.

Out into the two-way intersection crossed a pair of light tanks, their turrets fully turned toward the Cathedral – they had opened fire from around buildings before marching into the open. Behind them Adesh soon saw the noses of more Squire Infantry Half-tracks.

This was a full mechanized assault column heading toward them, not a probing attack.

The Corporal dropped his binoculars and shouted, “Down against the gun shield!”

Not a second passed since Rahani spoke that two shells flew against the steps.

One shot overflew them and smashed into the stone face of the cathedral, throwing down chipped rock atop the tarp erected over the gun. Another crashed at the foot of the steps and set shrapnel flying. Adesh heard the clinking of metal fragments against the gun shield, and he was shaken at first and found it hard to respond. But he collected himself – he could not afford this paralysis, not again. He huddled close to the gun, and Eshe and Nnenia crouched beside him as close as they could get for protection.

“Don’t fear it,” he said, out of breath, sweat dripping across his nose and lips.

Nnenia and Eshe nodded, staring grimly out over the park.

Nnenia passed Rahani a shell.

Behind them the doors to the Cathedral swung open, and a stream of men and women with various weapons rushed out to the trenches, to re-man the line on the northeastern corner of the cathedral and reinforce the southeastern trenches upon which the vehicles were now advancing. A small crew pushed out the 45mm anti-tank gun that had been stuck on the pulpit and set it between the two 76mm guns, aiming for the tanks.

Corporal Rahani grimly welcomed the newcomers, and ordered his own crew to traverse the gun, load and fire, aiming for the enemy’s light tanks that had them zeroed in.

“Load AP,” Corporal Rahani shouted. He punched the shell into place in the breech.

Adesh pulled the firing pin; across the park, one of the tanks approaching the tree line went up in flames as the shell penetrated its thin frontal armor and exploded inside, sending its hatch flying through the air. A second tank charged quickly up to take its place, and a dozen men huddled behind the newly burning husk for cover.

Sporadic mortar and sniper fire from atop the Cathedral crashed around the advancing Panzergrenadiers, but the armored figures of their moving vehicles and the smoking husks of their dead vehicles provided ample cover from the onslaught, and they were easily closing in on the first trench. Corporal Rahani loaded another AP shell handed to him by Nnenia, and while Kufu slightly adjusted the gun’s facing, the officer took his radio back from Eshe. He put in a call to their divisional command for support.

“This is Corporal Rahani on the Cathedral stronghold on Penance road reporting attack from enemy motor, armor, and infantry! I repeat, Penance road, Cathedral, under heavy attack! Requesting artillery support against the intersection on Penance road at the southeast corner of the Cathedral Park!” Corporal Rahani shouted.

He breathed heavily, waiting for a response.

In his hands the radio crackled. Rahani huddled with the crew, and Adesh listened in.

“Negative Penance, artillery is under tactical silence to support a spoiling mission underway. A relief mission for you will begin shortly. Hold out until then. Repeat: Artillery is under tactical silence. Hold out for reinforcement and relief. Spirits be with you.”

Two Squires on the intersection pushed forward along the road, and soon became four, and men began to hop the walls of their armored beds and deploy to the street, taking up positions, and organizing to charge; the one remaining tank crossing into the park green was also joined by two others. All of the tanks were lightweight and drove at the same pace as the half-tracks, boasting horseshoe-shaped turrets of riveted armor and carrying small guns. Their turrets were set centrally atop flat-fronted boxy hulls with tall rumps.

These were modernized M5 Rangers based on the old M2 Ranger.

Soon as they were spotted, the enemy tanks were engaged by the gun line.

Corporal Rahani ordered a shot downrange, and Adesh obliged.

The 76mm gun slid back; its AP shell crashed right in front of the lead tank. Almost simultaneously their partner gun fired, and a near-miss from its own 76mm shell managed to blow out the front wheel on the lead tank, marooning it in the middle of the green. This did nothing to its gun. It traded for their 76mm shell with one of its 37mm shots.

At the sight, Adesh flinched and hid behind the shield.

Again the shell crashed nearby, hitting the middle of the stone steps and forming a crater the size of a man’s torso. No shrapnel reached them, but the force of the shot caused their tarp to fall over and off the side of the steps, exposing them to rain. Smoke rose up before them. They were unhurt, but clearly soon to be outmatched.

Adesh felt a churning in his stomach – he girded himself again for the start of a real battle, praying to the Spirits for himself, for Nnenia, for Eshe, and for all their comrades.

“Should we go out there?” Gulab asked.

“Not until we have our orders from higher up.” Chadgura dispassionately replied. “Remember, we were sent here on a special mission. We will await special orders.”

Gulab heard boots along the ground as people in adjacent rooms rose to the commotion and rushed down to do their part. She heard numerous people storming through the adjacent halls and down the stairs. Minutes later she heard artillery – there was a slight shaking loose of dust from the ceiling, and a pounding of shells on the ground and against the stones. Were they trading artillery blows out in the lawn? This must have been a full-fledged attack.

And yet her unit waited in place for several minutes, until specifically roused.

There was a knock on their door, and one of the Privates answered.

She stepped aside, and from the hall a small woman approached the bed, and shook hands emphatically with Chadgura. She was a Svechthan, with short teal-blue hair and a dour expression that looked a touch unfriendly. Her uniform was dark blue, nearly black, part of the Svechthan Union forces training in Ayvarta.

Gulab tried not to stare – the lady was over a head shorter than everyone and her rifle, like a standard Ayvartan bundu, looked comically oversized for her. Svechthans were proportioned well for their adult size, but to Gulab they were still an unusual sight.

“Tovarisch!” She declared, “I am Sergeant Illynichna. Orders have arrived for you.”

Gulab noticed somewhat of an accent in her voice when she started speaking Ayvartan. Nonetheless she had rather good pronunciation, and made good word choices.

“Thank you, Sergeant.” Chadgura said. “Please go ahead. We are listening.”

Sgt. Illynichna cleared her throat. “Since the 25th, the KVW with the help of my Svechthan comrades has been using radio interception equipment mounted in half-tracks to gather intelligence on enemy positions within the city. We have gathered enough unencrypted short-range communications between various units to paint a clearer picture of their overall offensive preparations. Our mission will be to scout and disrupt those preparations to buy time for the Hellfire plan. Any Questions before we continue?”

“You’re coming too?” Gulab asked. She was the only one with any questions.

“Of course I am. I’m from the Joint-Training Corps OSNAZ – special tactics.”

Gulab had no idea what that meant at all. She shrugged and looked unimpressed.

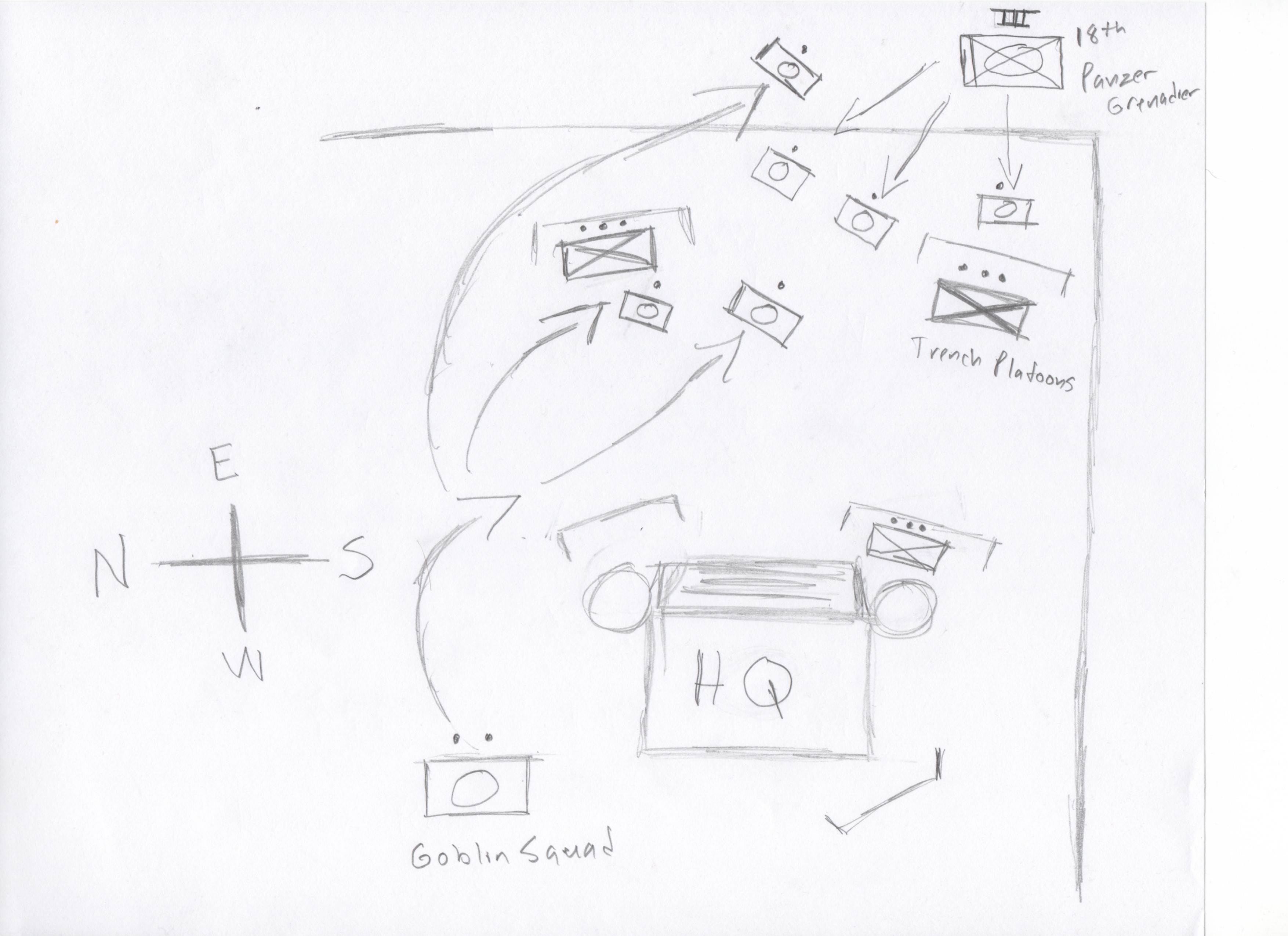

“Quit wasting my time duura!” Sgt. Illynichna said, calling her some insult she didn’t understand. The Svechthan girl produced a map of the southern district and laid it down over the bed. As a whole the squadron gathered around the bed to look at it, but Gulab found the symbols hard to discern. “Between Penance and Matumaini there were several evacuated industrial facilities. We believe Nocht will deploy their artillery and tank stations there. Their attacks along Penance and Umaiha will intensify in an attempt to pin us down away from the build-up areas. We must carefully scout Nochtish positions, then relay our findings so our artillery can bury them. A surprise saturation barrage will do the trick.”

“A sound plan. But I am remiss about using only a single squadron.” Chadgura said.

“It is necessary tovarisch!” Illynichna said. “We must take them by surprise. We will use a few tanks to hold back this assault on the Cathedral, and open up this road to the east, toward Matumaini,” she pointed out their route on the map, “but from there we must make our way quietly, like the arctic weasel. Strong head-on attacks are not feasible.”

Gulab supposed that it was easier for a Svechthan to talk about stealth since they were in general so small, but she held her thoughts on that, for fear of further upsetting Illynichna.

Chadgura nodded, and together she and Illynichna led the squadron out. Down in the nave, Gulab saw people rushing out the door, and she saw the guns outside firing against the tree line and the edge of the green turf. The 76mm guns boomed incessantly, their crews in a fever. Enemy vehicles trundled forward from the road, covering for squadrons of men in thick dark gray jackets and gloves, the panzergrenadiers. A rising tempo of anti-tank, sniper, and mortar fire slowed the enemy mechanized forces. Rifle squadrons stationed in the Cathedral rushed out to the trenches in turns, and gathered around the spires and steps.

Nocht improved their foothold on the intersection and the eastern side of Penance road, and their men assembled in the ruins and in the intact buildings. They began to open fire from across the road. This presence increased with each Half-Track allowed to park across the green. Norgler fire and mortars of their own had been deployed, and this sporadic fire punished the recrewing of the trenches. It was a slowly-building mayhem.

“It will get worse if we don’t find that artillery. Let us move.” Chadgura said.

Gulab snapped out of her reverie and nodded grimly.

She followed the two Sergeants out the back behind the Cathedral, where their half-track waited along with three Goblin light tanks. Before mounting the truck the squadron traded their rifles into a crate, and picked up short carbines with long, strangely thick barrel extensions provided by the Svechthan Sergeant. The carbines used magazines, of which they gathered many, throwing their own stripper clips into the crate with their old rifles.

“These are silenced Laska carbines, made in my home country.” Sergeant Illynichna explained. “Smaller cartridge than a regular rifle, but useful for sneaking around.”

Sgt. Chadgura lifted and toyed the small rifle, getting a feel for its weight and size.

“It is an invention of the Helvetians that we Svechthans tested to great results. They’re hard to manufacture, but worthwhile for special times. Its ammo is hard to manufacture too, so we cannot waste it.” Sergeant Illynichna added. “Hopefully it serves us well.”

“I believe it will. It is very easy to wield and aim.” Chadgura said.

Gulab looked down the sights. They felt a little small.

Still, it was a pleasant weapon to hold.

Once everyone was armed, they hopped into the back of the half-track and waited for the tanks to form up in front of them. The trio of Goblins started across the left side of the Cathedral, facing their strongest armor to the southeast, and charged toward the corner trenches. The Half-Track did not follow them. Instead it drove directly north, crossing the green out onto the road and circling around the park east. They drove with the tree line and the fences on the northern edge for cover and moved carefully to eastern-bound roads.

Above them the sky grew slowly furious.

Rainfall grew harsher, the drops larger and more frequent, the patter and tinkling of the rain working itself up to a drumming beat. Forks of light burned constantly within the heart of the blackening clouds, and distant, erratic thundering drowned out the trading of shells. Sergeant Illynichna grinned at the worsening weather overhead.

“Going out in that is good, tovarisch. Harder to be seen and heard in the driving rain.”

Around the park the battle intensified to match that black, rumbling sky.

From the back of the half-track Gulab saw the tanks engaging.

Across from the Cathedral, three Nochtish tanks had overtaken the first trench on the southeast and easily crossed it with their tracks, and the occupants were fleeing to the second trench line under fire from the tank’s hull-mounted machine guns.

One tank was at the head of the enemy advance, a third was farther behind it, and a second was practically hugging its right track. Their machine guns saturated the green in front of them, and their 37mm guns fired incessantly on the Cathedral, smashing into the spires, hitting the dome, sending shells crashing around the gun line at the steps the Cathedral. Their advance was haphazard but swift and vicious.

But their sides were fully exposed.

The Goblins were not seen until they had cleared the left wall of the Cathedral. They charged on the enemy in a staggered rank, each tank ten meters from the side of the next. The instant they left cover the three tanks braked and opened fire. Immediately they scored two hits – the tall engine compartment in the back of the lead enemy tank burst into a fireball, and its turret exploded from a second shot. These explosions sent chunks flying into a second tank to the right of the target, the shrapnel slashing deep into its turret.

Too wounded to continue, and perhaps having lost its gunner and commander, the second M5 backpedaled toward the trees and bushes for cover from further attacks.

The Panzergrenadiers halted their advance in the face of this reversal, hiding behind the smoking ruins starting to pile at the edge of the green. Ayvartan forces pressed their advantage. Small contingents climbed out of their holes to engage the enemy.

One Goblin remained in place and provided cover for rising trench troops.

Two others broke away from it, one headed directly for the road, its coaxial machine gun and cannon trained on the mechanized infantry, and the second hooking around the center of the green to chase the remaining tanks away from the Cathedral.

The KVW Half-Track stopped across the street from its connection out of Penance. They had the trees between them and the fighting. Only when the tanks had fully engaged the Panzergrenadiers and their vehicles on the road, and blocked their way farther upstreet, would it be safe for the Half-Track to cross. A Goblin tank crossed the green and drove onto the road, turning to face the enemy’s half-tracks and charging them.

The Goblin opened fire on the enemy while moving, perforating one of the half-tracks front to back with an armor-piercing shell. The shell exploded at the end of the bed, and its fuel tanks lit on fire from the violence. Panzergrenadiers on the streets hurried away, putting whatever metal they could between the Goblin’s machine guns.

Without warning a black plume erupted near the Goblin tank on the road, and the blast smashed the front wheels on its right track, paralyzing it in the middle of the road.

Subsequent blasts rolled along the road, some so close to the Nochtish line that even the Panzergrenadiers started to run, and the half-tracks to back away. Shells fell by the dozen every minute. One of the Goblins was abandoned, its crew leaping from the hatches as a fireball engulfed the machine’s exterior. The one stationary Goblin had its turret crushed by a shell, split open like a tin can, and its engine caught fire. Its slow movement back toward the Cathedral suggested people inside, still laboring in the flame.

Men and women ran right back out of the newly-reclaimed southeast trench, leaving it to be smashed by the creeping artillery. All of a sudden the Ayvartan battle line was contracting into a circle formed by the closest trenches to the Cathedral.

“Chort vozmi!” Illynichna cursed. “They’ve got their guns set up! Tell your driver to go! We must hurry and spot for our own tubes so we can counter-fire!”

Chadgura stuck her hand out the side of the bed through a hole in the tarp and signaled desperately. Up front the driver floored the pedal, and the Half-Track screamed across Penance and out to the connecting eastern road, putting several buildings between itself and the Panzergrenadiers. Gulab could not tell whether the rumbling and noise related to thunder or artillery. Both the fighting and the storm grew in intensity all at once.

Within the Cathedral a large radio set beeped and crackled, coming to life unbidden – the operator had become distracted with the battle raging outside the doors to the nave.

“All units report, urgent.”

Nobody seemed to hear or reply.

“Army HQ has lost contact with the Battlegroup Commander. We cannot confirm whether it may be related to the storm. Have any units managed to make contact with the Commander within the last hour? Repeat, Army has lost contact with Battlegroup Commander. Commander’s unit was last reported to be part of a surveying mission near Umaiha and Angba. Relay contact with the Commander back to Army signals. Repeat–”

NEXT Chapter In Generalplan Suden Is — Under A Seething Sky